Prospects for Syria to end-2017

With removal of President Bashar al-Assad no longer a serious option, factions are scrambling for territory

The war has entered a ‘post-regime change’ phase. The Assad government has been gravely weakened, but no longer faces a serious existential threat. The war is now largely a competition between various foreign powers and their Syrian allies to eliminate jihadis and position themselves for a nebulous post-war settlement.

What next

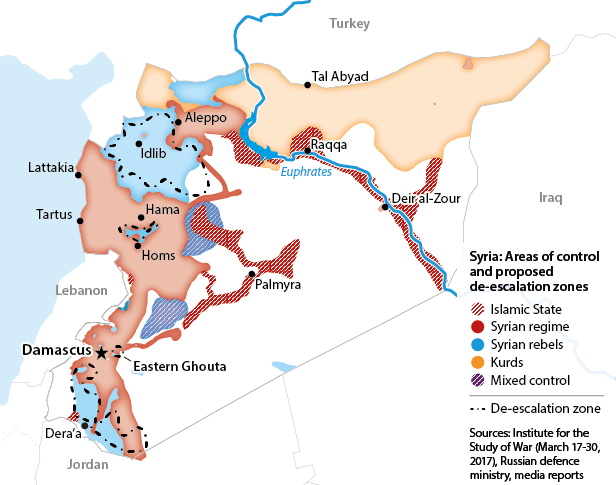

Warring Syrian factions and their international backers will race to seize former Islamic State (IS) territory in the east, but they will make limited headway. The Assad regime will consolidate its western stronghold, slowly grinding its way to military victory. An otherwise ill-starred agreement on ‘de-escalation zones’ will provide cover for Washington and Moscow to work towards a joint arrangement in the south.

Strategic summary

- Local factions’ prospects now largely depend on their alignment with foreign interests.

- The humanitarian situation will deteriorate, as aid dwindles and reconstruction funds do not materialise.

- An intransigent Assad regime will fail to rehabilitate itself internationally but remain in power.

- Turkey will intensify efforts to weaken internationally-sponsored Syrian Kurdish forces.

Analysis

More than ever before, Syria's war is now being driven by regional and international powers that have intervened to secure their own interests. Nonetheless, some local actors -- including the intransigent -- retain agency and, in some cases, leverage over their foreign patrons.

Opposition backers

While the opposition's state backers remain rhetorically committed to some form of regime change in Syria, most have abandoned it as a serious objective.

Washington

The United States is now focused on the fight against IS in eastern Syria around Raqqa, for which it relies primarily on the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG). It has also created a parallel, Arab force aimed against IS in Deir ez-Zour, which it is seeking to protect against pro-government forces (see SYRIA: Clashes could suck Washington into the conflict - June 7, 2017). However, that force has struggled to recruit in sufficient numbers to be effective.

The United States is unlikely to invest much in peace talks

In the west, Washington is pushing for de-escalation between opposition rebels and the Assad regime on an opportunistic, localised basis, but will not invest serious effort in negotiations processes or ceasefires that are unlikely to succeed. It may also step up counterterrorism operations against former Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and allied militants.

Ankara

Turkey will focus on weakening the YPG (which has links to its domestic Kurdish rebels) and disrupting its cooperation with the United States. However, it has few good options. Further air attacks on the YPG could risk hitting allied US forces, while a deeper ground intervention in north-east Syria might be costly.

Arab states

Jordan will remain ambivalent about the fight against the Assad regime. However, it will defer to its US ally's strong preference to keep Iranian-backed pro-Assad forces from approaching the Israeli-occupied Golan.

The Qatar crisis could hit some northern groups

If Saudi-led pressure obliges Qatar to stop funding armed groups, Ahrar al-Sham and Faylaq al-Sham, two Islamist factions active in northern Syria, would suffer most (see QATAR: Surrender to Riyadh will raise domestic risks - June 7, 2017). Any weakening of Ahrar al-Sham would allow its al-Qaida-linked rival, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), to expand in north-western Syria.

Regime patrons

Both Russia and Iran have compromised elements of the regime's sovereignty and possess leverage against Assad. However, they also have limited ways to exercise that leverage, particularly as Assad plays them against each other.

Moscow

Russia has successfully stabilised the Damascus government, yet lacks the means to deliver a conclusive settlement to the war. Assisting Assad towards total military victory would be a costly, long-term commitment. Instead, Moscow will try to broker a 'Great Power' agreement with Washington, on its own terms.

Russia's peace plans may fail

However, this is unlikely to succeed. The United States is sceptical that Russia's formulations -- for example, in the Astana negotiations -- can succeed. It is therefore unlikely to engage its own resources and credibility.

Tehran

Iran, for its part, remains committed to securing total victory for Assad while also strengthening its own regional deterrence architecture. Its near-term focus will be securing the Euphrates Valley link between Syria and Iraq via Deir ez-Zour. It is also entrenching its longer-term influence inside regime-held Syria through paramilitary proxy allies and new commercial interests.

Future Syria

With its allies' help, the Assad government has fended off all external existential challenges. It has solidified its hold on most of Syria's more populous, economically vital west, where only a few encircled rebel pockets remain.

Regime campaigns

The government is committed to ultimately recapturing the entirety of the country, but its limited manpower and brittle military oblige it to prioritise (see SYRIA: Local fiefdoms will undermine service provision - April 21, 2017).

IS's contracting zone of control in eastern Syria is now the prize. However, the regime will make limited headway. IS is likely to mount a more serious defence of its final stronghold of Deir ez-Zour than of the more peripheral areas it has surrendered recently.

Moreover, pro-government forces are overstretched. Damascus still faces military challenges in western Syria that will ultimately pull its forces back towards insurgent-held areas in the west.

Kurdish advances

The YPG faces a tough fight for IS's de facto Syrian capital, Raqqa, but will ultimately take the city. From there, it may move against IS territory further south, less for those areas' own strategic value than to obtain additional political leverage with Washington.

Despite its close collaboration with the US-led coalition against IS, the YPG is in a profoundly insecure position, surrounded by enemies including Turkey. It also controls large ethnically-mixed territories, whose residents resent Kurdish control. Eventually, it may have to moderate its ambitions and reach a stabilising arrangement with the Assad regime (see SYRIA: Turkey involvement will deepen conflict - September 9, 2016).

Opposition areas

Almost all non-IS, non-Kurdish opposition enclaves have been effectively neutralised. Most have been declared 'de-escalation zones' under an agreement between Russia, Turkey, and Iran in Astana.

The aim of this deal was to free up regime forces and turn jihadi and non-jihadi rebels against each other. Such infighting was already taking place in Eastern Ghouta, and there are indications of similar trends in the northern Homs countryside and Idlib.

Rebel-held Idlib province, in the north-west, is the most volatile opposition pocket (see SYRIA: Squabbling rebels will avoid showdown - March 20, 2017). It is dominated by jihadis such as HTS and other Islamist groups seen as 'toxic' by most of the opposition's state backers.

In the near term, nearly all international and regional powers will likely focus on keeping the north-west contained, while engaging in periodic counter-terrorism operations. Ultimately, however, the Damascus government is likely muster the forces and Russian air support to make inroads into Idlib.

Rebels also hold two 'zones of influence' sponsored by neighbouring states.

The Turkish-occupied area in eastern Aleppo province has few prospects for expansion, although Turkey is currently using it to recruit a 'national army' -- likely to be used against the YPG.

Rebels in southern Syria holding territory near Dera'a are backed by Jordan, with support from the United States and -- more quietly -- from Israel. However, the prospects of this 'de-escalation zone' are murky, with pro-government forces mobilising in the area.