Iraqi-Kurdish clashes near Kirkuk could spread

Internal Kurdish divisions have been brought to the fore as federal government troops take critical facilities

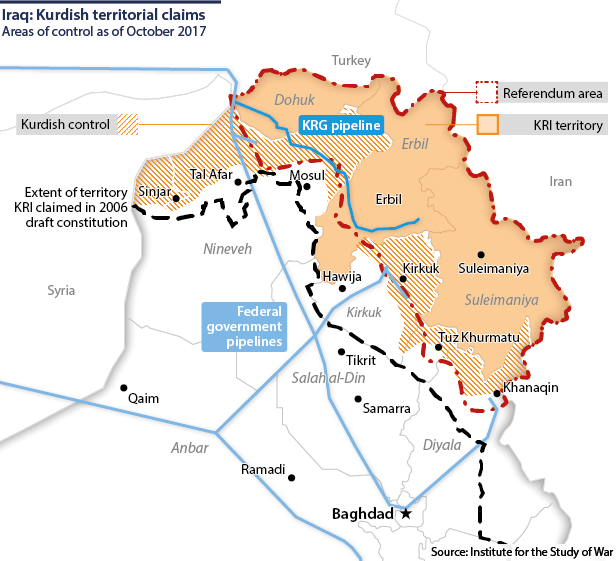

At least ten Kurdish peshmerga fighters were today killed in clashes with Iraqi security forces around the disputed city of Kirkuk, as civilians fled northwards. The federal government offensive began on October 13, after a rise in tensions following Kirkuk’s inclusion in the September 25 Kurdish independence referendum.

What next

The hopes of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi that Iraqi forces can retake key positions without provoking a wider confrontation are likely to be dashed, as the more extreme Kurdish nationalists and Shia militias seek to escalate the situation. This could weaken his own position. The US-led coalition against Islamic State (IS) will likely increase the pressure on both sides to negotiate; however, it may gain little leverage: the Kurds blame Washington for not intervening earlier and many in Baghdad believe that the referendum was a US plot to divide Iraq.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Fighting could spread beyond Kirkuk and Tuz Khurmatu to other disputed areas.

- The risk to Kurdish oil exports could raise international oil prices, but only slightly.

- IS fighters on the Iraq-Syria border will seek to capitalise on the infighting, likely with high-profile attacks against security positions.

- Fury over the ‘betrayal’ of Kirkuk could upset the balance of power in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Analysis

The September 25 Iraqi Kurdish secession referendum fulfilled a longstanding aspiration of the semi-autonomous region, and resulted in a 93% vote in favour of independence (see IRAQ: Kurdish referendum will go ahead on time - August 9, 2017). However, it also ignited a slow-burning political crisis.

Referendum fallout

Baghdad denied the constitutionality of the vote. The premier, Abadi, demanded that the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) should accept the territorial unity of the country and adherence to the national constitution prior to negotiations.

Kurdish President Masoud Barzani, for his part, insisted that negotiations should take place without any preconditions.

The rising tensions over how to manage the fallout from the referendum finally exploded in the key flashpoints of Kirkuk and Tuz Khurmatu (see IRAQ: Factions will seek territorial gains - July 28, 2017).

Kurdish peshmerga have controlled these disputed areas since they came under threat from IS in 2014. The KRI asserts a historic claim to them, but they are not part of its administrative region and are also home to other ethnic communities. As part of these historic claims, the referendum was also held in some of the disputed areas.

The referendum in these areas ruffled Baghdad, whose forces at the time had launched an assault against IS in Hawija, only 55 kilometres from Kirkuk. After this operation successfully concluded, however, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) warned on October 11 that these forces were mobilising against the Kurds -- in line with demands from the Iraqi parliament that federal forces should take over disputed areas, oil installations and border posts.

Abadi denied strongly that there was any intention of attacking Kurdish citizens, on October 13 calling all such reports "fake news" (see IRAQ: Referendum response will be measured - October 11, 2017). An army spokesman claimed that the purpose of the mobilisation was to move forces against IS in its remaining positions in Anbar province.

Kurdish cleavages

In fact, however, Abadi -- under pressure from angry Shia constituents to take some decisive action -- seems to have hoped that federal forces could peacefully return to key positions around Kirkuk through negotiation with the Kurdish militias holding much of the city associated with the mainstream faction of the Kurdish Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) party, controlled by the Talabani family. Initially, this met with some success.

On October 13, some PUK forces withdrew from two Turkmen areas south of Kirkuk, Taza and Bashir, in front of the Iraqi army's advance.

However, forces associated with the Barzani clan's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which spearheaded the push for the referendum, and other PUK factions, notably those loyal to KRI Vice-President Kosrat Rasul, responded with defiance.

Thousands of peshmerga reinforcements were brought into Kirkuk, apparently including KDP units loyal to the Barzanis. There were also violent clashes on October 14 in Tuz Khurmatu.

New rounds of talks were launched to avert a crisis, including key PUK and KDP leaders meeting on neutral territory to try to agree a common line. However, these efforts failed.

The Iraqi army therefore relaunched operations at midnight yesterday, using Taza as a launch point. Today it said forces its had taken full control of the K1 air base as well as key roads, bridges, energy facilities and the industrial district to the south of Kirkuk.

Intra-Kurdish rivalries are raising the tensions

The army claimed that the operation was entirely peaceful, as the pro-Talabani PUK fighters withdrew before its advance. This seems to be partly true, but there were also some clashes, casualties and rocket fire. Other PUK factions linked to Rasul and many local Kirkuk residents were enraged by this further withdrawal, and promised to retake the positions.

Future scenarios

Abadi's plan is likely to avoid any further escalation. Having reinserted the Iraqi security forces into locations within the disputed areas that they held before 2014 -- especially those related to oil facilities -- the premier will seek to ensure that any secession does not include these border regions, and to negotiate with the KRG from a position of strength.

In some respects, this could have been portrayed as a minor administrative change: the gas plant, power station and refinery taken this morning were already managed federally, but with peshmerga security. Baghdad emphasised that there was no plan to enter Kirkuk city. However, this will be a difficult line to sustain, given how polarised the positions have become in the last few days, and how high feelings have risen, especially among the KDP peshmerga and the Iran-backed Shia militias.

It is therefore likely that the recent clashes could escalate into wider fighting. Because of the mix of populations in Kirkuk, such a confrontation could become extremely bloody -- and many citizens are already fleeing. They fear an invasion of Shia militias whose leaders have been making strongly belligerent statements, despite Abadi's weak assurances they would not be involved.

In this scenario, there would be conflict in the disputed areas. The peshmerga would likely defend the main KRI territory successfully from any attempted incursion, but would suffer from increased economic pressure. Iran seems already to have closed its borders, and there are suggestions Turkey might also do, angered by the reports about PKK involvement.

If the situation deteriorates further, at least some oil exports might be stopped (see IRAQ: Wary investors will limit Kurdish oil output - February 20, 2017). It is even possible that the KRI could unilaterally declare independence, although this would gain no international support.

Such an escalation would cause deep concern to the United States, which needs Barzani as well as Abadi, and has heavily armed and funded both the peshmerga and the Iraqi security forces. Washington has urged both sides to avoid escalation and focus on the fight against IS. This now looks unlikely.

Iraq outlook

The fight against the Kurds will overshadow the fight against IS

In either scenario, continued high tensions between Baghdad and Erbil will firmly remove the focus from the task of mopping up the IS presence (see INTERNATIONAL: IS threat will persist for now - October 10, 2017). The Anbar offensive will likely be postponed. Emboldened, the salafi-jihadist group will plan large-scale suicide attacks against security installations elsewhere in the country.

The breakdown in ties will also have major implications for Iraqi domestic politics. Abadi could be weakened, not only because military actions on the ground have repeatedly belied his verbal assurances, but also because he can no longer rely on the votes of former Kurdish allies in parliament. Iran-backed Shia militias could become more powerful in the run-up to the 2018 elections (see IRAQ: Shia parties will hawk nationalist credentials - September 19, 2017).