Oil losses could bankrupt the Iraqi Kurds

The resignation of Kurdish President Masoud Barzani underlines the extent of the post-referendum debacle

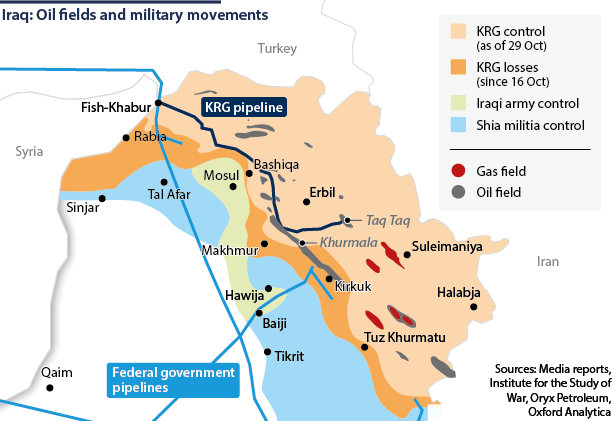

Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim today announced that Iraqi government forces had taken control of the Ibrahim Khalil border crossing between the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) and Turkey -- although Kurdish officials deny this. The border crossing is close to the vital oil pipeline tie-in at Fish-Khabur, where the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) oil export pipeline meets the federal pipeline (currently not operational) and continues through Turkey to the Ceyhan export terminal. Controlling this has been a key prize in recent fighting near Rabia, as well as in the US-mediated negotiations that followed a October 27 ceasefire.

What next

The fallout from the KRI's September 25 referendum will be devastating for the economy of the autonomous region, which is heavily oil-dependent. After losing most fields near Kirkuk (with another, Khurmala, still potentially under threat), the KRI will struggle to maintain production at current levels of 350,000 barrels/day (b/d). Control of Fish-Khabur could enable Baghdad to block Kurdish pipeline exports altogether, or set harsh conditions on their continuance. Expansion of gas production and exports, which had been looking more promising recently, will stall again. Even in the best-case scenario, revenues will be insufficient to cover public sector and military salaries, let alone debt payments to foreign oil companies.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The KRG will urgently seek a revenue-sharing deal with Baghdad to avoid economic collapse, but it is in a very weak negotiating position.

- If Baghdad takes control of the pipeline, covert ‘trucking’ of oil exports by various parties in the KRI will likely increase.

- Federal Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi will gain strength ahead of April’s parliamentary elections.

Analysis

Despite a 93% vote in favour, the secession referendum attracted near-universal condemnation, not only from Baghdad and regional players Ankara and Tehran, but also from Washington. Only Moscow was ambiguous in its attitude, perhaps reflecting planned hydrocarbons investments, but more likely as part of a wider bargaining game with Iraq and Turkey.

Domestically, the aftermath weakened Barzani and his Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), forcing his resignation on October 29 (see IRAQ: New offensive may crush Kurdish hopes - October 26, 2017). It also opened deep divisions with the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and other political groupings, which he accused of "high treason" in his resignation speech, resulting in attacks on party offices and journalists.

Oil grab

Abadi took advantage of KDP-PUK tensions to move military forces into Kirkuk on October 16, retaking the city and oilfields that had been controlled by the KRG since its peshmerga fighters moved in ahead of Islamic State (IS) in June 2014 (see IRAQ: Kirkuk clashes could spread - October 16, 2017).

On October 25, the Iraqi army and allied Shia militias also began to move towards Khurmala (the northern part of the Kirkuk field, operated by Kurdish company KAR) and the pipeline tie-in at the border point of Fish-Khabur. The peshmerga put up fierce resistance, aware of the economic significance of these two locations.

65%

Loss of former KRI oil output

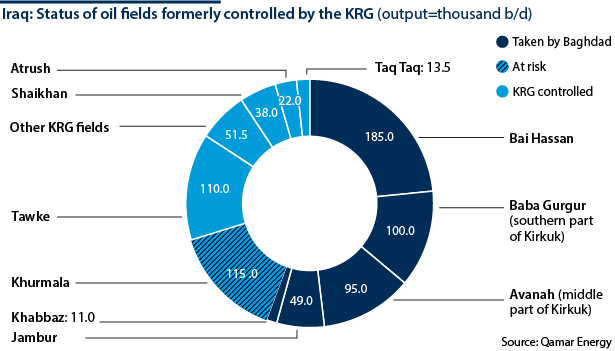

The KRI has lost access to 440,000 b/d of oil production from Kirkuk and surrounding fields. If Khurmala is also taken by federal forces, the KRI will lose a further 115,000 b/d from its remaining 350,000 b/d. Moreover, all its remaining exports are under threat if Baghdad takes full control of Fish-Khabur and either cuts the pipeline or demands that it should control and distribute all of Iraq's oil revenue as a condition of keeping it flowing.

The KRI's own fields and Khurmala provide an estimated 400 million dollars/month of oil revenues. This is not sufficient to meet KRG budget commitments of 700 million dollars, on top of which the government must pay oil company costs and reimburse pre-payments by oil traders as well as other debts. The KRG's total debt is now about 23 billion dollars.

Kurdish hydrocarbons outlook

There had been some positive developments for KRI oil and gas in mid-2017.

- In July, the Atrush field started production with an initial target of 30,000 b/d.

- In August, the KRG reached arbitration and restructuring deals ending disputes with former partners, encouraging the Pearl Petroleum consortium to agree to reinvest in the KRI.

- The government boosted cooperation with Rosneft, borrowing up to 3 billion dollars in oil pre-payments, and in September signing a deal for the Russian company to take an interest in five exploration blocks, purchase 60% of the region's oil export pipeline and build a 30-billion-cubic-metre/year gas pipeline to Turkey (see TURKEY/IRAQ: Kurdish ambitions could benefit Russia - July 24, 2017).

There is no money to repay oil-related debts

However, this hopeful outlook has evaporated following the loss of Kirkuk. Even if it retains control of remaining fields, the KRI will be unable to make payments due to Rosneft and other hydrocarbons firms.

This will prevent any further expansion of production and deter new investments. The gas export project, which could have been worth around 300 million dollars/month by 2022, now looks extremely unlikely, given new Turkish hostility to the KRG.

International oil firms are unsurprisingly losing enthusiasm.

- Production was already collapsing at Genel/Sinopec's Taq Taq field, once the region's flagship, because of overestimated reserves (see IRAQ: Wary investors will limit Kurdish oil output - February 20, 2017).

- Gazprom Neft had also left the Halabja block for geological reasons.

- ExxonMobil has relinquished another, while the Bashiqa block held by DNO and ExxonMobil is in disputed territories that are now lost to the KRI.

- Chevron has ceased drilling over security concerns.

Iraqi Kirkuk oil outlook

Production stopped when KAR left the Kirkuk fields; federal engineers need information and new equipment before they can restart. Moreover, Baghdad needs an agreement for these fields safely to resume exports via the pipeline through KRI territory.

In the short term, it has few alternatives. Iraq's Baiji refinery is too badly damaged to take the oil. Federal Oil Minister Jabar Ali al-Luaibi has announced plans to reopen Iraq's Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline, but this also needs major repair work after repeated attacks by IS.

However, the federal government is confident. Luaibi unexpectedly asked oil major BP to return to working on increasing output from Kirkuk, which they had previously studied in 2013 for the federal oil ministry. As operator (with CNPC) of Iraq's largest producing field, Rumaila, in the south, the company is likely to consider the request favourably.

The federal government has most leverage in oil negotiations

Iraq has already increased its large southern production of over 4 billion barrels/day to make up for Kirkuk losses. It is therefore under no great pressure to reach a deal with the KRI, particularly as this would mean breaching its OPEC commitments by even more than currently.

With the Kurds under pressure, Baghdad is likely to drive a hard bargain, seeking:

- federal regulation of exports;

- a return of the State Oil Marketing Organisation's control over exports from the Ceyhan terminal; and

- a favourable revenue-sharing deal where Baghdad receives the money for oil sales and then disburses the agreed share to the KRI.

Such a deal would be highly problematic for the oil companies that have been making deals with the KRI. Baghdad might agree to reimburse their costs, but not to pay their profits or settle debts, because it considers the production-sharing contracts they work under illegal. The KRI, for its part, would be unlikely to be able to pay them from its reduced allocation.

The massive loss of oil revenue could also destabilise the KRI by disrupting patronage networks on which the main political parties -- especially, in recent years, the dominant KDP -- heavily depend.