African anti-corruption will require state-led reform

The African Union adopted anti-corruption as its 2018 theme, in an effort to address a major impediment to development

The African Union (AU) on January 28 declared 2018 the ‘African Anti-Corruption Year’. In doing so, the AU explicitly recognised the corrosive impact of corruption on human, political and economic development, and on virtually all aspects of the lives of ordinary Africans.

What next

The prevalence of both grand and petty corruption across Africa may derail the AU’s efforts to improve human development through the goals elaborated in Agenda 2063. Effectively addressing corruption would require deep structural reforms within member states. The AU can help guide its members, but effective action can only be taken by states themselves.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Rwandan President Paul Kagame is expected to provide strong leadership as incoming AU Chairperson, but his approach may ruffle feathers.

- Expanding internet and social media use may change the ways populations hold politicians to account.

- The impacts of corruption will fall hardest on the continent’s poorest and most vulnerable.

Analysis

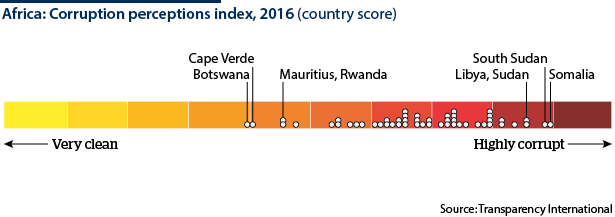

That corruption is a major problem in Africa is not in dispute. In Transparency International's latest Corruption Perceptions Index, of the 30 countries perceived to be the world's most corrupt, 17 (or 57%) are in Africa.

Nevertheless, Africans can take solace in the fact that four African nations -- Botswana, Cape Verde, Mauritius and Rwanda -- appear in the top 50 cleanest countries.

Agenda 2063

In 2013, the AU launched Agenda 2063, an ambitious development plan that seeks to secure the economic, social and political transformation of the continent by 2063.

Among the many aspirations enumerated in Agenda 2063 is Aspiration 3, which seeks to promote a culture of good governance and democratic values across the continent. The AU noted that these values are indispensable for the minimisation of conflict and the peaceful coexistence of ethnocultural groups, as well as for the successful delivery of development programmes that benefit the continent's poorest.

In focusing on corruption in 2018, the AU hopes to create momentum towards one of Agenda 2063's core pillars.

However, the AU has so far provided little guidance on how African countries can or should deal with corruption. Without further elaboration, Africans may have to look elsewhere for insights.

Learning from success?

Experience suggests that corruption is a problem that derives from the nature of a country's system of governance.

Corruption is fundamentally a problem of governance

Countries with relatively low corruption tend to have systems characterised by not only separation of powers but also effective checks and balances, including but not limited to:

- an independent judiciary;

- legislatures capable of challenging the executive;

- robust civil societies; and

- an independent press.

These checks and balances can constrain civil servants and politicians, minimising corruption and other forms of political opportunism.

Since the early 1990s, many African nations have democratised their political systems. Some have also adopted systems undergirded by the separation of powers. Unfortunately, many are still pervaded by high levels of corruption. This is because, despite their nominal transition to democracy, many still have weak and ineffective checks and balances, allowing political elites and civil servants to act with impunity.

Rule of law

A major reason why corruption has become so pervasive throughout Africa is the absence of laws and judicial mechanisms that can adequately constrain political actors.

Many persons implicated in corruption are not brought to justice, either because they have political connections and the judiciary dares not prosecute such 'untouchables' or because the judiciary itself is corrupted and its officers no longer perform their jobs effectively.

In Cameroon, despite persistent allegations, senior officials are rarely prosecuted for corruption, except when they run afoul of the president himself.

Beyond merely punishing perpetrators of corrupt acts, a functioning legal order can also actively promote and uphold constitutional values, thereby strengthening the democratic system.

In September 2017, when the Supreme Court of Kenya annulled the country's presidential election, the decision was lauded as an important development in the country's transition into a full democracy with institutions underpinned by the rule of law (see KENYA: Court ruling sets stage for new controversies - September 4, 2017).

However, the Supreme Court's verdict also exposed it to political backlash, including direct verbal attacks by the president whose election it overturned and an (as-yet-unsolved) armed attack on the deputy chief justice's car, raising fears of a campaign of intimidation (see KENYA: Political dialogue will face major impediments - November 17, 2017).

While it is too early to draw conclusions, one possible outcome of Kenya's experience may be a court that becomes more fearful of asserting its independence if other constraints on political power prove weak.

Presidential power

The prevalence in Africa of 'imperial presidencies' -- where presidents enjoy overwhelming power at the expense of other branches of government -- has been a significant contributor to corruption.

Many African presidents have been accused of using their positions to advance policies that generate extra-legal income for themselves, but which have negative social effects.

Where the president's powers are particularly unfettered, corruption is often deeper. This has been as true under traditional military dictatorships such as Sani Abacha's Nigeria or Mobutu Sese Seko's Zaire as it has under the current generation of semi-democratic presidencies such as Joseph Kabila (Congo), Teodoro Obiang (Equatorial Guinea), Jose Eduardo dos Santos (Angola), Robert Mugabe (Zimbabwe) or Paul Biya (Cameroon).

Unfettered presidential power remains a major contributor to corruption

Even where such systems have not produced corrupt presidencies, as appears to be the case in Paul Kagame's Rwanda, structural power imbalances mean those societies may face risks should a new leader assume power.

Hence, anti-corruption will only be effective and sustainable in the context of a balanced power relationship across the branches of government, where executive power can be constrained from abuse.

Unfortunately, many recent constitutional reform efforts have tended in the opposite direction. Over recent years, countries such as Burundi, Cameroon, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda and Uganda have passed or sought to pass constitutional amendments that either strengthen presidential powers or extend presidential mandates (see AFRICA: Risks to democratic governance loom in 2018 - December 21, 2017 and see PROSPECTS 2018: East Africa and the Great Lakes - November 24, 2017).

Civil society

Constitutional constraints are an important prerequisite, but they are not in themselves sufficient to minimise corruption. Effective civil societies that act as a check on government are also required, allowing citizens to punish recalcitrant politicians through the ballot box.

In Ghana, anti-corruption was a major plank of President Nana Akufo-Addo's 2016 election campaign and eventual victory -- though he may yet face challenges in implementing his promises (see GHANA: New president will face key economic tests - December 12, 2016).

Meanwhile, in South Africa, while the judiciary and anti-corruption institutions are strong on paper, executive control allowed graft to flourish under President Jacob Zuma. Since December's election of Cyril Ramaphosa as ANC leader -- and presumptive future national president -- authorities have belatedly started to pursue a range of corruption cases (see SOUTH AFRICA: ANC will push anti-corruption priorities - January 16, 2018 and see SOUTH AFRICA: Corruption inquiry may aid Ramaphosa - January 26, 2018).

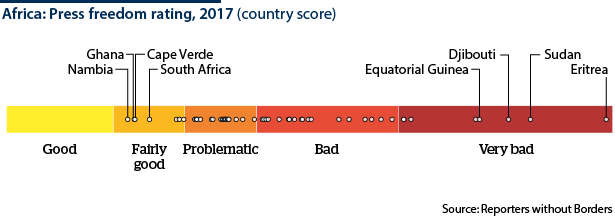

All these checks can be strengthened by an independent press that can expose corruption and pave the way for prosecution or political action.

Unfortunately, in Reporters without Borders' 2017 World Press Freedom Index, only seven African nations -- Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Comoros, Ghana, Namibia and South Africa -- were rated as 'fairly good' for press freedom. In comparison, 46 were rated as 'problematic' (20), 'bad' (18) or 'very bad' (8).

Outlook

Given the centrality of governance to corruption, while AU leadership may be important, an effective anti-corruption programme can only be delivered through reforms at the national level. AU frameworks, commitments and cooperation may facilitate such efforts, but ultimately success will depend upon the efforts of individual countries and their citizens to institutionalise and protect democratic institutions that adequately constrain the state.

_350.jpg)