US actions raise agricultural trade costs globally

US trade aggression is prompting its partners to retaliate against US farming -- risking an escalation of restrictions

On July 1 Canada imposed tariffs worth 12.8 billion dollars on several US export sectors, notably agriculture, in response to the US tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium from Canada. US President Donald Trump last month targeted Canada’s supply management system for dairy, poultry and eggs as an example of unfair restrictions on agricultural exports to that country. Meanwhile, Canada, Mexico, China and the EU, the largest US farm export markets, are imposing retaliatory measures on key agricultural and food imports from the United States in response to US tariffs on steel, aluminium and Chinese manufactured goods.

What next

Talks will continue but, in the meantime, the tariffs will disrupt agricultural markets, trade and supply chains and risk encouraging more restrictions. Negotiations about NAFTA may resume in the wake of the Mexican elections, but the US tariffs on steel, aluminium and potentially also automotive products imported from NAFTA partners make it less likely that Canada and Mexico will grant concessions on agricultural or other outstanding issues, either within NAFTA or bilaterally. The ramifications will influence the US congressional elections in November.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The tariffs will disrupt agricultural markets, trade and supply chains globally, and commodity price volatility will increase.

- Food security and price stability worries will rise and may spark a vicious circle of more restrictions and interventions by governments.

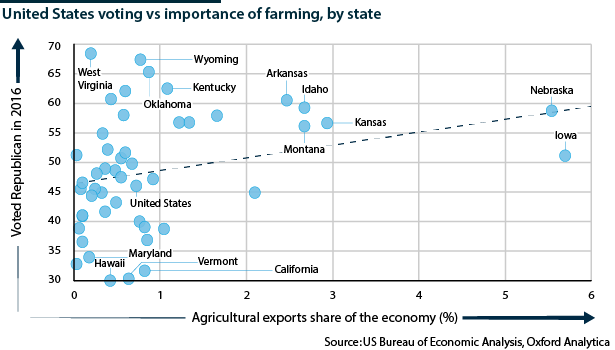

- Chinese retaliation is targeting US agricultural and processed food exports, affecting activity in ‘swing’ states ahead of the elections.

Analysis

Governments set agricultural policies to enable them to stabilise markets, respond to negative impacts on their farming sectors and guarantee food security. The US actions go far beyond this.

Ironically, the G7 communique underlined the importance of a rules-based international trading system and vowed that governments would strive to reduce tariff barriers, non-tariff barriers and subsidies. However, in the near term, the number of non-tariff barriers, domestic subsidies and interventions is likely to increase across the world in response to US trade actions.

Multi-decade progress

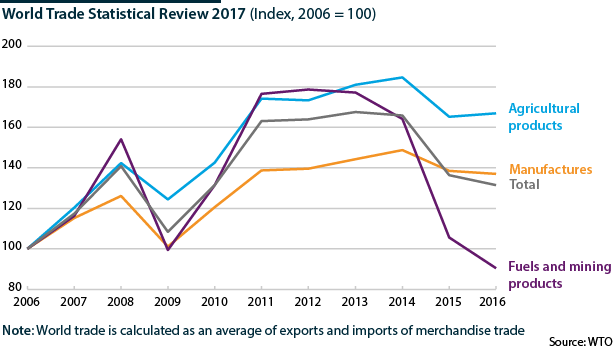

Agricultural markets and policies have made substantial progress over the past two decades and trade in agricultural products has grown rapidly -- at around twice the pace of total global trade -- since 2000. Nevertheless, agricultural trade and domestic support policies remain contentious.

Demand is rising in line with populations and incomes. Changing patterns of production are also contributing, most notably increasing demand for biofuels. Agricultural production, exports and growth are shifting to emerging economies, especially South America and southern, central and Southeast Asia (see BRAZIL: Agriculture outlook shows promise this year - February 12, 2018).

These trends, together with shocks including climate events and government decisions, are driving agricultural prices and influencing agricultural policy trends. Growing demand, higher prices and rising trade flows have lowered average applied tariff rates and export restrictions globally.

Multilateral negotiations have stalled in recent years, but most bilateral and regional trade agreements now include tariff cuts and agricultural market access concessions that exceed commitments individual countries have made under the WTO. These agreements also tend to include provisions for technical assistance, WTO-plus frameworks for sanitary and phytosanitary measures and stronger limitations on export restrictions and subsidies.

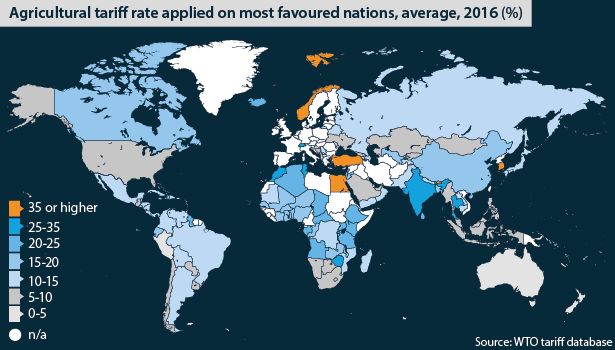

Yet barriers persist

Nevertheless, significant tariff and non-tariff barriers persist. Tariff rates on certain products are set at levels that effectively reduce or exclude imports. In the case of tariff rate quotas, any imports above the agreed quota are charged at a higher rate to protect domestic producers.

Despite substantial liberalisation, tariff and non-tariff barriers still prevail in agriculture

High import tariffs on Canada's supply-managed products are a good example.

The 1993 WTO Agreement on Agriculture obliged Canada's supply-managed sectors to switch from a regime of controlling the number or mix of imports allowed to a tariff rate quota system -- for example, taxing dairy products above a certain quota at 270%. The Canadian supply management system was introduced in 1995 to coordinate output and demand and imports of five products -- dairy, chicken and turkey products, table eggs and broiler hatching eggs.

Many other countries also impose high duties on imports in economically or politically sensitive sectors, including US tariff protection for sugar, cotton and, to a lesser extent, beef, peanuts, tobacco and certain dairy products.

Moreover, bilateral and regional trade negotiations often incorporate non-tariff barriers, including the use of regulatory measures, marketing and price controls (another feature of Canadian supply management), restricting licensing and distribution and protection of rules of origin. All significantly impede agricultural trade.

Supporting suppliers

Canada's supply management system allows federal and provincial governments to avoid directly subsidising farmers. In many other countries, government subsidies for agricultural production have grown over the past 20 years (see CANADA/US: Supply management is likely US target - May 2, 2017).

Producer support has remained stable among more developed OECD countries but has increased significantly in emerging economies where governments have tried to encourage domestic production to support rising economic development and incomes. Government policies have converged over the same period. Most governments are directing their domestic support programmes to supporting farmers' incomes generally, rather than subsidising specific types of production.

Non-OECD economies now account for over half of the world's producer support spending, up dramatically from 4% 20 years ago, and the sharp increase in food prices experienced between 2007 and 2009 led many governments in emerging markets to adopt domestic food security policies to try to stabilise prices and promote domestic self-sufficiency.

Many are taking a more active interventionist role, imposing input subsidies, market price supports, output-based payments, public stock holding programmes and temporary export restrictions. These measures have a high potential to distort trade, exaggerate long-term price volatility and reduce global food security.

Among OECD economies, these measures are less prevalent as governments prefer to adopt income support programmes for households independent of production levels. The use of insurance programmes to deal with risks is also increasing, as are investments in the use of new technologies, infrastructure, and research and development.

Retaliatory tariffs

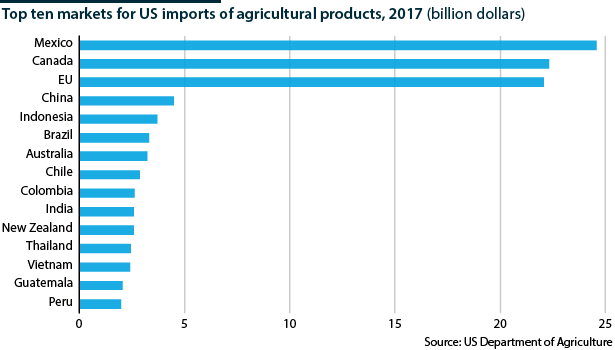

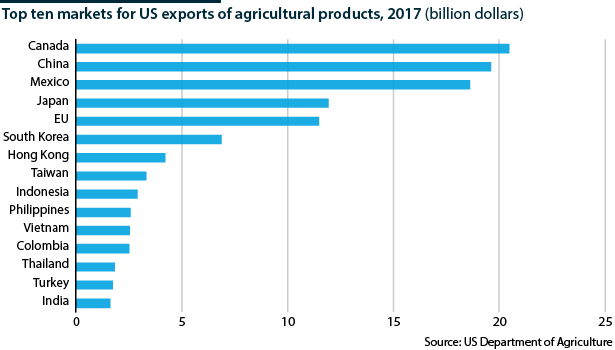

China, Canada, Mexico and the EU are the four largest export markets for US farmers, together accounting for just over half of the 140 billion dollars in agricultural products exported from the United States in 2017, as well as for most of the growth in US export sales (see EU/US: Agriculture could prove undoing of trade deal - February 27, 2013).

All four are imposing retaliatory tariffs on imports from the United States equivalent to the value of trade affected by the new tariffs the United States is to apply on imports of steel and aluminium. The US tariffs on Chinese manufactured goods are due to come into effect on July 6. China will start its retalitory tariffs on the same day.

The retaliatory measures target agricultural and food products from vulnerable Republican constituencies -- bourbon from Kentucky; pork products, corn, soybeans and sorghum from the Mid-West; prepared foods from the northern states; orange juice from Florida; certain cheeses from Wisconsin; and fruits, nuts, rice and tobacco from southern states.

Impact

If they take effect for a prolonged period, the retaliatory tariffs will have a number of negative impacts:

- They will reduce international demand for US agricultural exports (which account for approximately one-third of domestic agricultural production) and erode the trade balance in a sector in which the United States enjoys a large surplus.

- They will depress prices for affected agricultural commodities and farm incomes across integrated North American markets. Fears of Chinese retaliation have already caused futures prices to fall sharply.

- Global market price volatility will increase.

- Competition within North America will also increase, although opportunities will be created for agricultural exporters outside the United States, including producers from Canada, Mexico, South America, Australia and Asia.

- Tariffs will disrupt existing supply chains for food processing and agriculture-related industries. US manufacturers of agricultural equipment will be hit hardest, as steel and aluminium costs rise when customer demand falls.

- They will also aggravate concerns about food security and price stability in developing countries.

Policy response

There are two alternative long-term outcomes, but the near-term risk is that, even if all sides agree concessions to avoid disputes escalating and the costs of trade spiralling, the higher prices that consumers and businesses will face will discourage them from spending. As a result, even if an agreement can eventually be reached between the United States and its trading partners, medium-term global growth prospects could already be damaged.

The permanence of the US policies is uncertain, but the doubt is dampening growth prospects

Tariff turnaround

The first scenario is that the economic damage to the US agricultural sector and the resulting political reaction will exert sufficient pressure on the Trump administration to induce it to drop or reduce US tariffs on steel, aluminium and Chinese imports and to soften its demands with respect to Canada's supply management system.

There are signals that this may be possible. Farmers in all three countries strongly support the existing NAFTA deal (see INTERNATIONAL: No NAFTA would have extensive effects - December 21, 2017). In the aftermath of the G7 meeting, US Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue stated that the United States is not trying to stop supply management but to limit the supply of unregulated Canadian milk solids that are currently depressing US prices.

If the Trump administration can see that US exporters are making progress towards expanding the markets in which they can sell, tariffs and hard-line demands may prove short lived.

Vicious spiral

However, the opposite scenario currently appears more likely. The US trade actions and retaliatory tariffs will encourage more restrictive agricultural trade practices (see INTERNATIONAL:Testing trade alliances and architecture - June 18, 2018).

The US administration's 'America First' trade actions and the president's public comments about unfair practices on the part of its closest trading partners are already causing international customers to look for sources of supply from outside the United States. US actions are hardening government policy positions on agriculture and other trade issues.

Trump's post-G7 comments induced Canada's parliament to pass a unanimous resolution in support of supply management. This will give Canadian negotiators less flexibility to make future concessions with respect to the policy.

Similarly, China was prepared to open its market to 70 billion dollars' worth of US agricultural and energy imports if the United States did not impose the threatened tariffs on certain Chinese manufactured goods. China has withdrawn this offer following the imposition of the tariffs.

Concessions could come eventually

However, the goalposts are changing regularly. All sides remain open to talks (see PROSPECTS H2 2018: Global economy - June 1, 2018).

Energy trade is one area in which the United States could find middle ground with both the EU and China. The EU wants to diversify its energy supply beyond Russia and the Middle East, and China's population and income levels are growing rapidly, requiring more energy. Matching these aims, the United States is keen to export more liquefied natural gas.

Predicting the timing of US policy changes is difficult, however. In the meantime, the retaliatory measures will increase the likelihood of new discriminatory non-tariff barriers being imposed on agricultural trade.

In emerging markets, market disruptions and a spike in Chinese demand for agricultural goods from markets outside the United States to replace the goods it previously imported from the United States will heighten concerns about food security and price stability.

This could lead to more producer subsidies, market price supports, public stock-holdings and export restrictions.