Prospects for the global economy to end-2018

Policy and trade trends, and geopolitical risks are diverging across the world

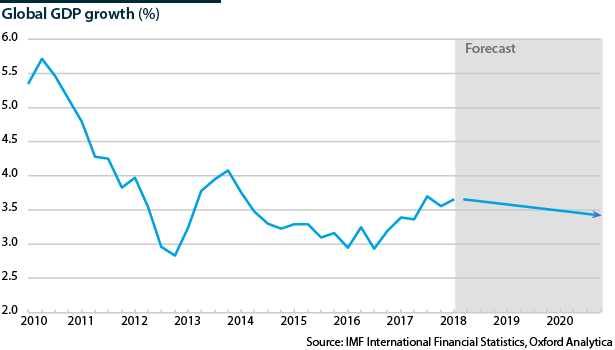

The world economy is expected to grow by around 4% this year, slightly higher than expected six months ago. Yet this is likely to be the peak of this cycle.

What next

Growth looks set to ease in 2019 but the likelihood of a global recession is low. Nevertheless, concerns will persist about trade, the scope of monetary policy to respond to rising financial market instability and the lack of potential for fiscal policy to meet rising needs for structural reform. Against this backdrop, even a mild economic shock could lead to a more prolonged -- if shallower -- downturn than seen in 2008-09.

Strategic summary

- The combination of OPEC supply decisions, Iran-World relations, supply shocks and US output will direct the oil price in the rest of 2018.

- The US-China trade truce is fragile, as is the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade agreement and US-EU relations.

- ECB monetary policy decisions are delicately poised and will determine the divergence with US policy, influencing the dollar's trajectory.

- Monetary conditions are tightening, implying that advanced and emerging markets that have built up dangerous debt levels will be at risk.

Analysis

Global growth has momentum, but risks from trade disputes, geopolitics and financial markets are high.

Tax cuts and higher spending have modestly boosted US activity, but euro-area growth is slowing. US rates are rising, offsetting US political risks and strengthening the dollar but pressuring financial markets across the world. Fuel prices have risen by more than 20% this year, boosting the growth prospects of net exporters but increasing inflation and curbing growth in net importers.

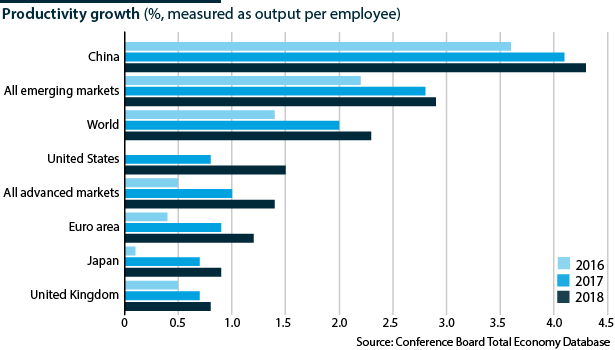

More promisingly, there are signs of the long-awaited productivity pick up.

Commodities constraints

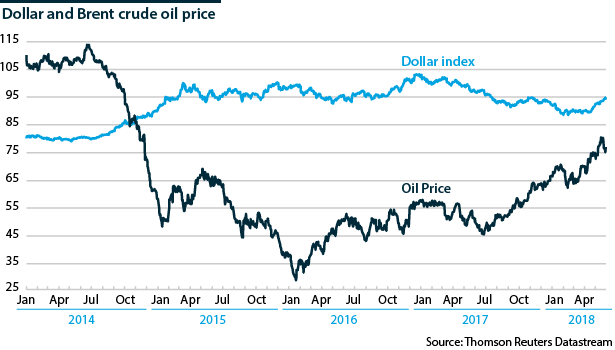

Oil is trading at 75-80 dollars per barrel, against last year's average of 55 dollars. Unexpected delays to bringing production onstream have damaged the belief that the flexibility of US shale to increase output in relatively short order would cap prices closer to 50 dollars per barrel than 100 dollars. Prices for delivery more than a year out are also higher.

The re-imposition of sanctions on Iran by the United States and many of the countries it does business with has tightened the supply strains that the OPEC output cuts introduced.

Reflecting these constraints, the IMF estimates that supply restrictions account for 80% of the price rise since September. However, the New York Federal Reserve Oil Price Dynamics monitor argues that 50% is due to demand, which has risen sharply since 2010-2013. Higher prices are expected to reduce demand; the International Energy Agency has cut its global oil demand forecast for this year by 100,000 barrels per day (b/d) to 1.4 million b/d.

Supply strains will persist, but the combination of weaker demand and higher US output will keep oil prices at 60-90 dollars per barrel.

OPEC is the wildcard. Its members' stocks are at their lowest in three years. Russia and Saudi Arabia have discussed relaxing the exiting1.8 million b/d cuts by 1.0 m/d. The group meets in Vienna on June 22.

Trade trajectory tinged with tension

Concerns eased rather than disappeared after US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced that the goods trade dispute with China is "on hold" (see INTERNATIONAL: US/China self-sufficiency is dangerous - April 4, 2018).

Re-heightening tensions and sharply raising the risk of retaliation, the United States will impose a 25% tariff on its imports of steel and 10% on its imports of aluminium from the EU, Canada and Mexico from June 1.

Trade worries include:

- the highly uncertain fate of the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA);

- growing tensions between the EU and the United States following the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal; and

- the US Commerce Department's Section 232 (national security threat) investigation into auto imports, given the centrality of automobiles and their related industries to both NAFTA and US-EU trade.

4.4%

WTO forecast of export volume growth in 2018

Nonetheless, trade is growing steadily. The WTO estimates that global goods export volumes will grow by 4.4% this year, little changed from 4.7% last year before slowing to 4.0% in 2019. Using forward-looking indicators such as orders and transportation trends to assess conditions, the WTO trade outlook indicator forecasts a slight softening in the April-June quarter.

Productivity picking up

Productivity is picking up in the United States. Non-farm output per hour rose by 1.3% year-on-year in January-March up from 1% in 2017, encouraging hopes of a global revival. US GDP could expand by close to 3.0% this year, with output per hour growing by 1.5%, closer to its 1985-2015 level (see INTERNATIONAL: 2018 is key for a productivity rebound - February 5, 2018).

Higher fuel prices should help stimulate mining investment, raising growth prospects in commodity-exporting emerging markets, especially in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and Russia. Higher raw material costs will lower profit margins in some sectors, but financing remains historically cheap globally despite higher US rates.

The most substantial US tax reform for 30 years will free cash for investment by lowering US firms' tax bills and incentivising investment, although some incentives will not be available until the 2020s. Solid growth will also increase the pressure on firms to invest although action will vary. Many firms may be cautious, with money going into research and development rather than capital investment.

The combination of robust demand and higher investment, including into new technologies, sets the stage for productivity gains around the world.

Financial fragility

Monetary conditions are tightening.

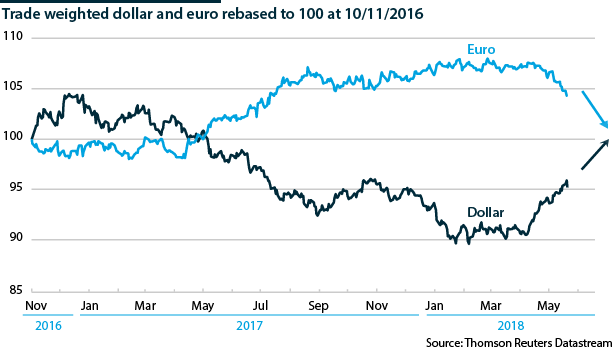

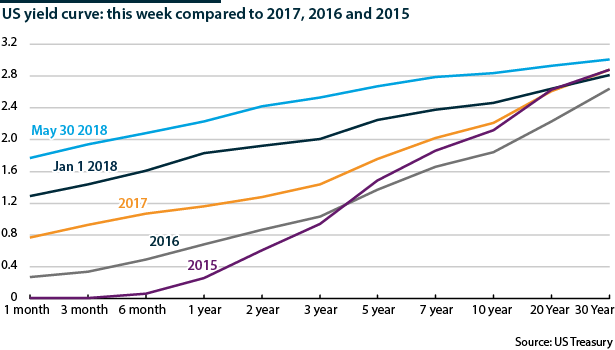

The Federal Reserve (Fed) is reducing its balance sheet and the US ten-year benchmark yield is stable near 3.0% after averaging 2.3% last year. Since mid-April, the trade-weighted dollar has strengthened by 5%. The euro carries 60% weight in the dollar basket.

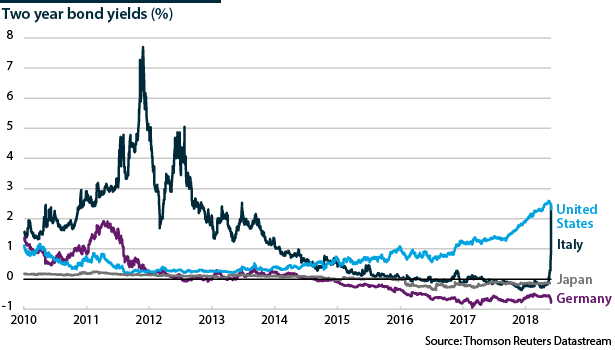

Over the same period, easing euro-area activity and rising risks in Italy have dragged the euro 6% lower against the dollar. The divergence is likely to continue.

Dollar strength pressures economies dependent on dollar financing. Turkey runs a large external deficit and owes more than 250 billion dollars in foreign currency, largely in dollars. The lira has lost nearly 20% of its value to the dollar this year see TURKEY: Low monetary credibility keeps strain on lira - May 30, 2018). Payments on the local currency debts of more than 150 billion dollars will also be costlier as the policy rate is 16.5%, double a year ago.

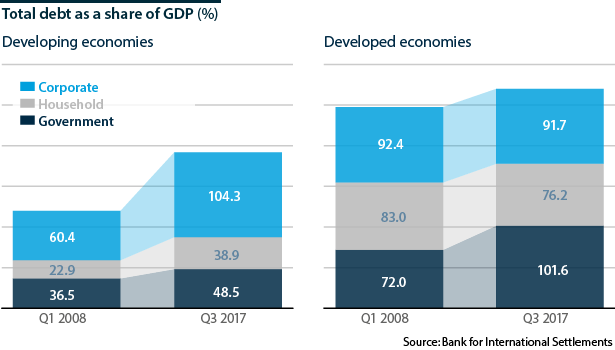

Other countries could be forced to raises rates faster than would be ideal for activity as emerging markets debt accounts for nearly 200% of GDP, up from less than 120% ten years earlier. Advanced markets debt accounts for 270% of GDP, from less than 250% over the same period.

High yield but lower quality bonds are also vulnerable. Some US stock market sectors are overvalued, raising the risk of a sudden slide. The S&P 500 index is 33% higher than the start of 2015 but telecommunications and information technology stocks in the index are 62% higher.

Crypto assets will attract increasing attention. The low leverage of the cryptocurrency market and the low correlation with the mainstream asset classes means the near-term risk of a bitcoin-induced broader sell-off is remote. However, the asset class will expand in use and value will increase the risks and the need for coordinated regulation (see INTERNATIONAL: Cryptocurrency regulations will vary - May 10, 2018).

Advanced countries -- United States

Expectations of US inflation feeding through to wages and rate rises have driven up the dollar and the ten-year bond yield, and the yield curve is flattening, However, there is little evidence of higher wages. Core inflation, excluding food and energy, is 2.1% and private hourly wages rose by 2.6% year-on-year in March and April, keeping real wage increases modest.

Underlying this is the high number of prime-working-age people that the workforce has not reabsorbed since 2008-09. If job growth continues at the current rate, it could take two-and-a-half years to regain the same ratio of workers to population as pre-downturn levels.

The latest Fed meeting suggests that the committee would be happy for inflation to "modestly overshoot", seeing underlying inflation as little changed and the risks as balanced. The Fed is expected to raise rates by 25 basis points in June. One more increase between July and December is looking as likely as two.

1 or 2

Fed rate rises expected in the second half of 2018

This would be consistent with GDP growth averaging 3.0%, slowing towards 1.5-2.0% over the medium term. The budget boost will fade but pressure from retiring baby boomers will leave little fiscal room for manoeuvre and a higher risk of crisis (see UNITED STATES: Budget sustainability questions rise - April 12, 2018).

US monetary and fiscal policy trends are diverging. Fiscal policy is expansionary, although one caveat is that only 13% of the 1.5 trillion-dollar infrastructure plan is federally funded. State, local and private sources are unlikely to provide anywhere near 1.3 trillion dollars.

Euro-area

One of the most important drivers of the dollar will be the degree to which global growth weakens relative to US growth. Euro-area GDP grew by 0.4% quarter-on-quarter in January-March, down from 0.7% in July-December 2017.

Moreover, political risk is rising in Italy after the victory of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement and the far-right League in the March 4 general election (see ITALY: Fresh elections in September are likely - May 29, 2018).

Financial markets were calm between the election and the announcement of the government's programme on May 19-20 but likely inability of the coalition to form a sustainable government is taking its toll. A leaked coalition agreement outlines plans to ask the ECB to write off 250 billion euros (295 billion dollars) of debt and says that if there is "popular will" it would seek to leave the euro.

On May 29, the spread between Italian and German two-year yields rose by more than in the 2011-12 sovereign debt crisis. While the spread has eased, borrowing costs will remain higher than from January to mid-May (see ITALY: Fragility is Europe’s biggest risk into 2018 - September 5, 2017.

Policy

After September, the ECB is due to stop buying 30 billion euros of sovereign bonds each month. Supporting this, economic activity still has solid momentum even though growth has slowed and while inflation is below target, higher energy prices are applying pressure. However, consumer activity is already weakening and lower real wages could intensify this.

The ECB is likely to reduce the size of the purchases but extend them. If activity continues to slow, core inflation remains far below target and Italian uncertainty remains high, this becomes even more likely. ECB President Mario Draghi's cautious comments confirm that an abrupt end is unlikely. Another option is to stop the purchases but to raise rates very slowly over the medium term.

Europe's monetary outlook is murkier than the United States'

In contrast to the United States, fiscal policy is neutral. Balances are better following years of austerity but there is little appetite for expansion. The EU 2021-27 budget shifts spending towards migration, border control, defence and digitalisation.

GDP growth of 2.3% in 2017 may be the peak but 2018 growth should hold up above 2%, slowing towards 1.0-1.5% from 2019-20.

Japan

Expansionary policy and robust global growth are not stimulating investment and consumption is disappointing. Annualised GDP contracted in January-March and investment fell the most since 2015.

Two temporary factors contributed: poor weather and less stock building. Inventories could rebound, facilitating a smaller GDP decline or a small increase in April-June. However, with trend growth entrenched at 1% or less, recession will never be far away.

Having started his second five-year term in April, Governor Haruhiko Kuroda no longer expects inflation to reach 2% by 2020. The asset purchase programme could continue for his whole term to 2023.

Emerging markets

Trends influencing the outlook include the following:

- Costlier oil boosting growth prospects and budgets in net exporters but dampening growth prospects, reducing real incomes, and widening budget and trade deficits in net importers.

- Higher US rates increasing worries among investors about the ability of dollar indebted emerging markets to pay debts; the IMF has already helped Argentina avoid default.

- China's prioritising of growth at close to 6.5% to 2020 should help world trade maintain momentum.

China

Having exceeded the target in January-March, growth is set to slow to 6.5% in the rest of the year (see CHINA: Sustainable growth initiatives will dampen GDP - January 19, 2018).

The President's Work Report at the five-yearly party Congress in October focused on improving the quality of growth and lowering inequality through reducing overcapacity, deleveraging, innovation and expanding social security.

China's leadership has recommitted to its 2010 centenary goal of doubling aggregate and per capita GDP by 2020, requiring annual growth of at least 6.3%.

Relegating the sustainability agenda is disappointing but reflects rising risks. Trade risks have not disappeared. Intellectual property transfer is a concern. Goods trade also remains at risk. More manufacturing self-sufficiency is crucial to the decades-long shift of US policy towards autarky.

Nor have risks from a sharper property slowdown disappeared -- housing investment rose by 10.2% year-on-year in April, but sales by floor area fell 4.1%. Sharply lower prices would dampen consumer spending.

In the 2020s, GDP growth will slow to 5-6% and efforts to curb debts and pollution will be ramped up. However, the cost of curbing them will also have risen, which could take growth below 5%.

India

GDP growth picked up in January-March 2018, but the higher oil price is increasing price pressures, curbing monetary scope and widening the budget and external deficits (see INDIA: Higher oil prices hit economic prospects - March 1, 2018). Price pressures and financial volatility could force the Reserve Bank of India to cut rates sooner than would be ideal.

This will make it harder for authorities to achieve their target of 8% growth from April 2018 to March 2019, and will make it difficult for the government to improve its economic credibility before the 2019 general elections. In the medium-term, India's commitment to digitalising its economy should pay off, ensuring that, combined with other favourable factors, it grows above 7%.

Russia

President Vladimir Putin is targeting GDP growth above the global average as he begins his final six-year term. Higher commodity prices might fuel 2018 growth of more than 2% for the first time since 2012, but this will far short of estimated global growth close to 4%. Low investment and unfavourable demographics make 4% medium-term growth a pipe dream.

Brazil

GDP growth is picking up, possibly to 3% in 2018 from 1% last year. However, this could be the peak. Whoever wins October's presidential election is not expected to have a legislative majority, leaving the next government without a reform mandate.