Prospects for nuclear arms control in 2019-23

In an already confrontational atmosphere, abandoning nuclear arms treaties will increase mistrust and risky behaviour

Russia and the United States have reached an apparent impasse on nuclear weapons. Presidents Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin warn of the dangers of a new nuclear arms race, but neither appears ready to make the concessions necessary to salvage the current arms control and non-proliferation regime. Attending a NATO foreign ministers' meeting yesterday, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo set a 60-day deadline for Russia to comply with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

What next

The 1987 INF treaty will be the first casualty, formally expiring six months after Washington submits an official notice of withdrawal, although it is in effect dead already. Next is the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START); agreement to extend it by five years beyond 2021 is looking unlikely. Although some high-level nuclear dialogue will continue as part of strategic stability talks, the damage to wider nuclear non-proliferation goals may be irreparable.

Strategic summary

- Washington intends to withdraw from the INF treaty; Russia is open to negotiations to salvage it.

- Both Russia and the United states will consider placing intermediate-range missiles in Asia.

- The end of New START will eliminate important transparency and verification mechanisms.

- Strategic stability talks will continue as a risk-mitigation mechanism.

Analysis

Trump confirmed in October that Washington intends to withdraw from the INF treaty, which outlaws ground-launched missiles with a range of 500-5,000 kilometres. The message was delivered directly to Moscow during a visit by National Security Advisor John Bolton.

The Kremlin condemned the decision, arguing that it would undermine strategic stability between the world's two principal nuclear powers and damage global security.

The pathway for negotiations to salvage INF appears increasingly narrow.

Claims of violations

Washington's argument for withdrawal is based on its insistence that Russia has tested and deployed the 9M279 land-based intermediate missile (NATO designation SSC-8), in breach of INF.

This has raised a verification problem, which the sides have been unable to resolve through the INF's Special Verification Commission (see US/RUSSIA: INF treaty end will destabilise Europe - October 22, 2018).

The dispute is complicated by Russian allegations of US treaty breaches relating to ballistic-missile defence systems and certain unmanned aerial vehicles.

New build-up

Russia has said that it is open to talks to save the INF treaty, but warns it will take steps to protect its national security and interests. This is likely to involve 9M279 deployments in the European theatre, made easier by compatibility with existing short-range missile launchers.

Moscow has a missile ready and places to base it; Washington does not

The United States has plans to develop intermediate-range missiles, but many of its NATO partners will be reluctant to host them. Some Central-East European states might be more willing, primarily to secure a larger US troop presence.

Washington is likely instead to pursue the line set by the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review: improving 'tailored deterrence' capabilities in Europe by developing lower-yield nuclear warheads for ballistic missiles and sea- or air-launched cruise missiles (see UNITED STATES: Success of new nuclear arms not certain - February 6, 2018).

East Asian deployments

The breakdown of INF raises the prospect of Russian and US deployments in the Asian theatre.

Russia views China as a growing economic partner and a political ally against the West, yet it will make provision for a hypothetical deterioration in relations. China's conventional military is vast and increasingly capable, and now fields advanced 'anti-access/area denial' (A2/AD) systems.

Moscow's best deterrent option would be to place mobile intermediate-range missiles in Siberia, capable of striking targets anywhere in China.

Washington, too, may consider deploying land-based intermediate-range missiles, as cheaper than sea-based systems and more resilient against China's A2/AD capabilities, while reassuring US regional allies and discouraging them from pursuing nuclear options independently.

One possible scenario is that the threat of US and Russian deployments persuades Beijing to consider joining INF or a new iteration of the treaty.

Preliminary trilateral conversations among US, Russian and Chinese experts have taken place, but there has been no serious expression of interest from Beijing. A broader INF treaty would require China to eliminate its intermediate-range arsenal while the United States and Russia did nothing (see CHINA: Beijing will keep nuclear 'no first use' pledge - July 2, 2018).

START stops

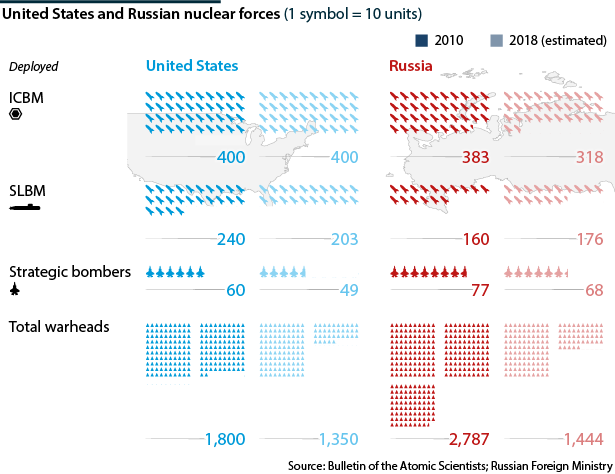

The New START treaty expires in 2021, unless Moscow and Washington agree to extend it by five years (see US/RUSSIA: Nuclear arms treaty may lose relevance - April 24, 2017).

An extension looks unlikely, not because either side wants to exceed its still-generous missile quotas, but because of deepening distrust between US and Russian leaders in multiple areas that make it unlikely the two sides can sit down and agree to preserve this foundational arms-control instrument.

A worrying consequence of ending New START is that the legal instruments for mutual inspections will disappear. Even if neither party substantially increases its arsenal, reduced transparency in a confrontational political climate increases the risk of unintended escalation.

New START has built confidence that no one is cheating

As in 2009-10, when the previous START agreement lapsed while New START was still being negotiated, a new US administration could change course, but it is difficult to envisage this occurring without broader, greater positive shifts in bilateral relations.

Opportunities to talk

Formal agreements aside, there are still opportunities for high-level dialogue on nuclear issues in the 'strategic stability talks' format. The most recent round was held in Helsinki in September 2017.

These dialogues are not intended to replace treaty negotiations, but rather to 'fill in the gaps' between agreements and anticipate future challenges. Their agenda to date has been comprehensive, with issues raised by both sides ranging from allegations of treaty violations to the potential for 'multi-lateralising' existing treaties or developing new ones.

Without progress on treaties, strategic stability talks will likely focus on other issues, principally addressing technological change such as cyber attacks on early-warning and missile launch systems, the weaponisation of space and the implications of new long-range conventional weapons.

Another important purpose of such talks is to open windows into each other's culture of strategic decision-making. How each side thinks about its core national security interests, how messages and signals are interpreted, and what threats and scenarios might cause political leaders to consider using nuclear weapons are vital matters for both Moscow and Washington to understand.

Proliferation risks

The greatest cause for concern in the next five years may be the erosion of the global nuclear non-proliferation regime.

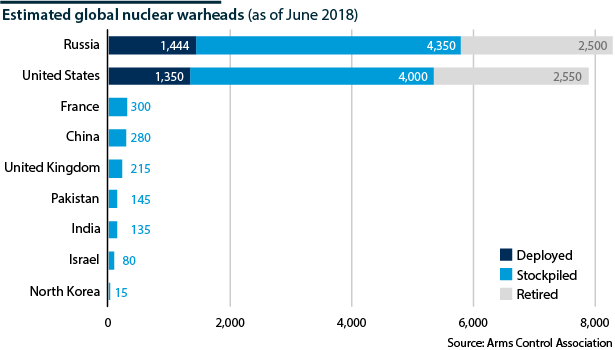

The 1970 Treaty on Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) provides the basic architecture for recognising the right of the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom and France to possess nuclear weapons while other signatories are prohibited from developing them.

This bargain is made possible by the commitment of nuclear-armed states to work towards eventual disarmament. Progressive cuts in US and Russian arsenals have been a strong argument for persuading non-nuclear states to remain in compliance.

If INF and New START disintegrate, the signal to non-nuclear states will be that Russia and the United States are not serious about disarmament.

This question will come to a head at the 2020 NPT Review Conference, the first full meeting to consider a proposed ban on all nuclear weapons, approved by the UN General Assembly in 2017 despite objections from all five nuclear-armed NPT states.

The end of US-Russian arms control will complicate international efforts to pressure Iran and North Korea to disarm. With the world's two nuclear superpowers setting an example of renewed confrontation, other regional powers in East Asia and the Middle East will be inclined to seek their own deterrent capabilities.