West adopts diverse defences against cyber meddling

The DNC hacking and its impact on US politics is a cautionary tale for governments and the press

Data hacks and cyber ‘kompromat’ operations can influence domestic politics in democracies with a free press, as evidenced in the 2016 US presidential election. Consequently, governments, politicians and the media are recalibrating their responses.

What next

Western officials are applying lessons from each attempt at political meddling via cyber tools. This backward-looking bias means solutions to future attacks will be imperfect, but is unavoidable. Successful hacks will serve to boost populist movements that discredit the political centre. Nonetheless, increasing public awareness about disinformation and fake news, especially on social media, will over time make voters more resilient to leaked data.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Most European countries will strongly penalise social media for GDPR violations.

- US regulators will remain less hostile to the interests of ‘big tech’.

- Russian actors will constantly adapt their new campaigns to Western defences.

Analysis

After the Democratic National Committee (DNC) computer network was hacked, major US media outlets printed stories based on data stolen from presidential candidate Hillary Clinton's campaign.

They said they had no choice but to report them since the contents of Clinton's emails were newsworthy. Belatedly, The New York Times admitted that in their willingness to distribute the hacked information, US newspapers became "a de facto instrument of Russian intelligence".

US defence

Ahead of the November mid-terms, the US federal government, private sector and civil society launched a massive - and, by all accounts, successful -- effort to avoid a repeat of 2016:

- The government organised a three-day series of simulated cyberattacks; officials from 45 states participated.

- The Department of Homeland Security placed new sensors on databases that house voter registration information to monitor web traffic.

- The Department of Justice announced a policy of alerting US private organisations and individuals early.

- Facebook and Twitter increased their efforts to shut down malicious accounts and stop false information from spreading.

The US government also adopted a more assertive cybersecurity policy (see UNITED STATES: Aggression risks deeper cyber conflict - October 4, 2018).

The measures appear to have been successful thus far: the mid-term elections were free of the kind of cyber incidents seen in 2016.

Other countries have learnt from the US experience but adopted slightly different approaches.

French firm hand

In 2017, the Russian hacking group 'Fancy Bear', the same advanced persistent threat actor that was linked to the US hack, published 9 gigabytes of data from then presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron's 'En Marche!' party during the French election campaign.

The documents appeared online an hour before the start of a campaign blackout, which meant none of the presidential candidates was able to comment.

French authorities responded differently from their US counterparts:

- The electoral commission appealed to the media not to publish information from the documents, highlighting the need to preserve the integrity of the elections.

- A warning was issued that circulation of hacked information could be classed as a criminal offence.

Mainstream media complied, even though Le Monde newspaper had seen part of the documents.

French authorities have gone a step further with social media. France is engaging in the 'co-regulation' of Facebook by sending a small team of senior civil servants to the company for six months to verify how Facebook deals with online hate speech. This approach is modelled on how France deals with its banking and nuclear industries.

The French government sees such intrusive checks as 'smart regulation', a superior alternative to legal, rules-based approaches, the application of which can often be misjudged when done from the outside.

German caution

Berlin is balancing privacy and protection

In December 2018 sensitive and stolen data from 944 German politicians, celebrities and public figures were posted on Twitter. All the main German political parties were affected except the far-right Alternative for Germany.

A 20-year-old German national was arrested earlier this month and has confessed to the crime. Reportedly, no government networks were breached.

Even so, Germany cybersecurity protocols are set to change:

- The justice ministry is considering stricter security regulations for software manufacturers and internet platforms.

- The interior ministry is examining an 'early warning system' to allow Twitter accounts that illegally distributed data to third parties to be shut down more quickly.

Lessons from the hack will also feed into a new IT Security Law 2.0 which will be adopted later this year. The law will introduce a new IT safety certification for equipment such as routers (see EUROPE: EU eyes cybersecurity as competitive advantage - December 19, 2018).

The government also plans 35 new posts at the Federal Office for Information Security and 160 cybersecurity roles are being created at the Federal Criminal Police Office.

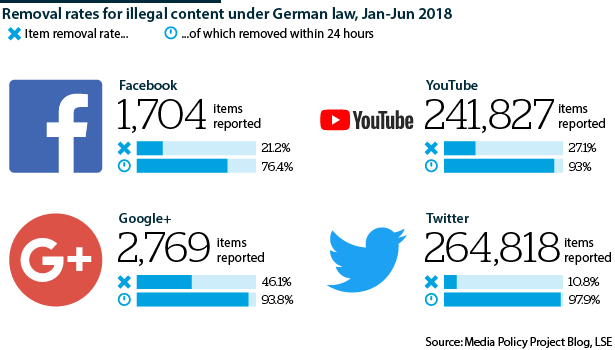

Berlin may also penalise Twitter for the leak. Previously, it has dealt with social media platforms in a manner different from the French approach. As Europe's leading privacy advocate, Germany introduced the Network Enforcement Act, obliging social media firms to remove hate speech and other illegal posts within 24 hours of receiving a notification or face fines.

German mainstream media are also cautious:

- The chief editor of Der Spiegel magazine has acknowledged that US media were weaponised and manipulated after the DNC hack.

- Discussing the same hack, the political editor of Bild said that if his paper were to come into possession of stolen emails, it would highlight in red every paragraph where leaked information is used and inform readers that the information was leaked in order to manipulate their opinions.

Sweden's collaborative response

Sweden is collaborating with the private sector

Sweden's government is working actively with the private sector, social media organisations, broadcasters and newspapers:

- A 'Facebook hotline' was created to allow officials quickly to report fake Swedish government pages.

- The government launched a nationwide education programme in schools on propaganda; leaflets on how to detect misinformation were distributed to 4.7 million households prior to the September 2018 election.

- Officials have received training in detecting online influence operations.

Other states are attempting piecemeal changes:

- The Netherlands abandoned electronic counting of votes in its 2017 general election due to concern over hacking.

- Canada has created a new Centre for Cyber Security to protect its democratic institutions from cyberattacks ahead of 2019 federal elections.

Outlook

Governments are treating the theft of data more seriously, recognising that politically motivated cyberattacks rarely occur in isolation and are usually part of larger malicious campaigns.

Yet none of their measures is foolproof -- data hacks will continue while cyber hygiene is imperfect -- but Western governments, mainstream media and social media firms are better equipped to deal with the effects of cyberattacks.

Recalibrating social media use

In the United Kingdom, Parliament's 'Health and Wellbeing Service' advised MPs to close their Twitter accounts in July 2018. This is unlikely to happen as Twitter provides a valuable tool for politicians to engage with their constituents; nearly 600 of the country's 650 MPs have Twitter accounts.

However, Western politicians will become more careful about using social media platforms for casual commentary and personal correspondence. They will likely focus on using their accounts to communicate prepared scripts.

Already in 2017, the German Bundestag's speaker requested legislators not to use electronic devices to tweet or share news about proceedings in the chamber. After the December hack, the leader of the Greens party cancelled his Twitter and Facebook accounts, as have several other politicians.

Boosting mainstream communications

Governments will reinforce their press offices to deal with leaked information better and reassure voters. The UK National Cyber Security Centre is actively pursuing this defence.

When deciding whether to print hacked information, mainstream media organisations will balance short-term publicity gains against long-term risks of political interference.