Huawei dispute risks escalating reprisals from China

US-China 'strategic competition', symbolised by the dispute over Huawei, will have serious global ramifications

The US Justice Department yesterday filed several criminal charges against Chinese technology major Huawei and its chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, who was recently arrested in Canada at Washington’s request. The development raises the prospect of retaliation against North American companies from Beijing, which is already incensed by US tariffs and restrictions on technology exports and investment. This fear is reinforced by the recent arrest in China of two Canadians and an Australian.

What next

Political risk has increased for the value chains of large Western multinationals, especially those critically reliant on Chinese subcontractors. Companies are well advised to manage their potential exposure by doubling up value chains to include alternatives outside China. That would also insure against interruptions due to ever-more-frequent natural disasters. Yet such diversification will be neither quick nor easy nor cheap.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Lower-wage countries have an incentive to streamline their domestic business climate, but reforms will be slow.

- Chinese firms will increase their investment in fast-growing South and South-east Asia.

- This will accelerate the trend towards fewer global value chains and more regional ones.

Analysis

Western business people are ensnared in low-level court proceedings in China far more regularly than is reported in the West, and the risk remains low of a retaliatory move against a Western executive of similar status to Meng.

Such a move would undercut the high ground that Beijing has occupied as self-appointed defender of the 'rules-based international order'.

However, there are other ways for Chinese authorities to take reprisals against Western multinationals operating in China should they so choose:

- Day-to-day operations can be interrupted through inspections, audits and other tourniquets of red tape, and by the selective application of Chinese civil, administrative and criminal law.

- There is also the possibility of travel bans on executives (including on those facing unresolved court proceedings), and intimidation.

Pressure on Chinese firms

China can make its firms act 'patriotically'

Such reprisals could escalate in the context of the unresolved trade tensions between the United States and China.

In particular, Western multinationals, including large US technology companies, that use China for assembly or as a source of semi-manufactures or components have an additional vulnerability: their value chain.

Local suppliers of large Western firms and their subcontractors are susceptible to pressure to act 'patriotically', when authorities convey the message, however tacitly, that non-cooperation with foreign multinationals is in the national interest.

Chinese consumers have on earlier occasions read signals indicating that they were meant to boycott Japanese and South Korean products.

There are many ways to apply informal pressure along the value chain, from delaying delivery to easing quality standards. Suppliers and subcontractors could find themselves suffering sudden and 'unexpected' shortages of inputs or labour disruption.

Challenges to diversification

Several companies have started to reconfigure their value chains where possible, particularly those vulnerable to US national security concerns because they incorporate Chinese technology into their end-products (see INTERNATIONAL: Huawei's 5G kit has security weakness - January 4, 2019).

Yet diversifying supply chains can be neither easy nor cheap (see CHINA/US: Tensions risk unravelling tech value chains - January 3, 2019).

China has accumulated a vast manufacturing ecosystem servicing foreign companies, encompassing everything from hard infrastructure to soft skills. Its growth has accelerated in recent years as China has embraced automation as way to offset rising wages that could make it less competitive as an offshoring centre.

Therefore, building up a parallel value chain is not simply about shifting to another low-wage country. Both the quality and quantity of China's manufacturing skills, particularly in the areas of automation and robotics, deter companies from relocating elsewhere in South or South-east Asia.

Apple Chief Executive Tim Cook, for example, recently noted that one of the main reasons why his firm remains committed to and dependent on China for its value chain is China's vast talent pool of tooling engineers.

Lower-wage countries such as Vietnam and Cambodia have little production or skilled human capacity to spare, even in relatively low-skilled sectors such as textiles and garments, let alone the advanced precision-tooling, materials-handling, process-engineering and development skills that a US technology company needs.

Nor do those countries have the resources to develop them rapidly.

Accelerating trend

Nonetheless, a parallel process of value-chain reconfiguration has been under way in some sectors with a regional focus.

Production of end-products and components, ranging from bicycle parts to computer hard drives, has started to relocate -- lower-tech from China to Indonesia, Cambodia, Bangladesh and India, higher-tech to South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia. Vietnam straddles the two.

Burgeoning middle classes in South and South-east Asia provide a growing market for China's consumer and industrial goods, especially for non-luxury goods that do not need the cachet of a US or European brand.

Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand are all forecast to join the world's 20-25 largest economies during the second quarter of this century, alongside India and Indonesia. Moving production nearer to those markets makes sense.

China's market

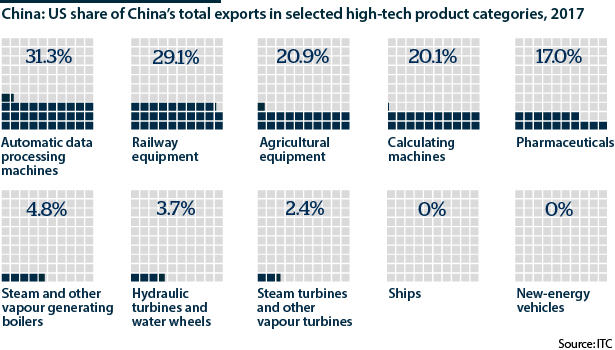

Chinese companies will be compelled to seek alternatives to the US market in response to Trump's tariffs, especially those that have become US-reliant, further accelerating the changes to regional trade and the value chains that support it.

The overall effect will be that more value chains will begin and end in China, rather than beginning in China and ending in the United States.

Regional value chains

Regional value chains have an advantage: they are shorter than global ones

As global value chains have become longer and leaner, they have also grown more fragile, just as the pressures on them are increasing from:

- reputational exposures;

- environmental concerns, such as carbon footprints;

- technological change -- particularly artificial intelligence, robotics and big data; and

- shifting relative labour costs.

The Trump administration's trade policies will provide new impetus to the developing patterns of multiple, shorter regional value chains, but the transformation will take time.

Reconfiguring a value chain can take as much time as rebuilding a manufacturing plant. Companies will hesitate to jump into new developing markets where investment laws can be unclear or nascent -- such as in Myanmar, Cambodia or Vietnam -- and where labour and environmental standards are lax.

Nor will it be easy to replicate established relationships with factories, suppliers and governments.

Complicated electronics value chains, in particular, are so entrenched in China that all business is unlikely to shift elsewhere as a result of the new tariffs alone.

Chinese constraints

For its part, China itself still depends on specific imported technologies such as chipsets and sensors.

This constraint will ease as China develops, with some urgency, local capacities in these technologies, not least because Washington is set on preventing the export of crucial US technologies and blocking Chinese companies from gaining access to them through inward foreign direct investment.

Dual technology world

The current US pushback against China's 'strategic competition' will further fracture value chains, with part of the world running US technology to US technical standards, and part running Chinese technology to Chinese standards. There is no certainty that the hardware, software and services from these two sources will be interoperable and once a market is locked into either of the systems, it will be difficult for users to switch. China would welcome this decoupling: it would allow its firms to dominate fast-growing developing markets.

This will add complexity to value chains, making it more likely they will default to specialising regionally. Manufacturers and suppliers may develop parallel value chains, one to supply the West and the other China, calculating that gains from maintaining commercial access to such large markets will outweigh the complexity and cost of doing so.