China-Africa debt trap myth may obscure real dangers

China has been accused of geostrategic manipulation in its lending practices to Africa, but the reality is more complex

Amid fears of a new African debt crisis, China’s role as a major development financier faces increasing scrutiny. However, the ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ debate mischaracterises the underlying mechanisms driving Chinese lending while obscuring the legitimate reasons to be wary of Chinese financing practices.

What next

Chinese loans will remain a major part of Africa's debt landscape, but are unlikely to rise significantly, as Beijing imposes stricter regulations on overseas lending. Most Chinese loans will go to much-needed infrastructure projects. However, implementation may be underwhelming, as elite deals with little transparency result in inflated costs and poor environmental and social safeguards, while some host governments fail to manage debt trajectories and development projects responsibly.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Washington will try to use the ‘debt-trap’ angle as a lever against Chinese influence, while its own Africa strategy remains slow and vague.

- As Chinese-backed projects face more scrutiny, host nations may impose tighter requirements and rework or cancel some existing projects.

- Amid domestic concern over slowing growth and profligate spending, Beijing may tighten regulations to prevent funding of unviable projects.

Analysis

Some 14 years after the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) helped cut Sub-Saharan Africa's indebtedness by two-thirds, the continent's external debt levels are rising again (see AFRICA: Revenue diversification would reduce debt - January 11, 2018).

Though concomitant with increased global borrowing, African nations have accumulated debt much faster than other low- and middle-income countries.

The combined external debt stocks of the 30 African countries that benefited from MDRI have doubled since 2010, with debt generally outpacing economic growth.

External debt stocks in some countries -- including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia -- have risen over 200% in the last decade. The IMF currently assesses 18 African countries are in or at high risk of debt distress.

Moreover, the composition of African debt has changed since MDRI. Today, commercial lenders and non-Paris Club lenders, notably China, hold a much greater share of African debt than before, resulting in a riskier, more complex financing landscape.

China's emerging role as a development financier throughout the 'Global South' has been widely criticised by Western -- especially US -- actors.

They accuse Beijing of 'debt-trap' diplomacy: essentially, predatory lending practices that lure states into accepting unsustainable debts they must inevitably default on. This is presented as part of a geostrategic ploy to gain international influence and secure strategic assets overseas.

Critics often point to Sri Lanka's Hambantota port as a prime example. Hambantota was built mainly with Chinese funds and ultimately turned over to China Merchants Port Holdings on a 99-year lease when Sri Lanka struggled to service the loans.

Nevertheless, Hambantota is the only identifiable example of debt-for-equity among nearly 3,000 projects financed by Chinese banks.

Elite-led development

Closer examination of the drivers, mechanisms and logics behind Chinese lending to Africa provides little support for the debt trap myth.

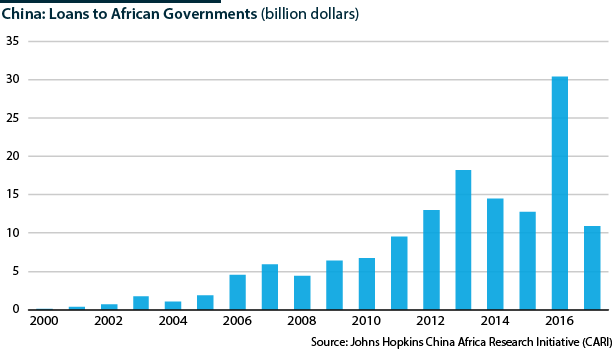

China is now Africa's largest single creditor nation, having loaned some 161 billion dollars to African states between 2000 and 2017.

Nevertheless, Africa's Chinese debt stock is less notable when juxtaposed with overall external debt, approximately 20% of which is owed to Chinese lenders, compared to 35% to multilateral institutions and 32% to commercial lenders.

Chinese loans are the largest contributor to debt distress in only three countries: Republic of the Congo, Djibouti and Zambia.

Moreover, Beijing will likely be open to restructuring these deals, as its developmental discourse aims to portray South-South cooperation as less exploitative than North-South engagement. Over the last 15 years, Chinese lenders have restructured or waived debts on 84 occasions.

Meanwhile, the debt-trap narrative ultimately mischaracterises the internal logics of Chinese commercial expansion by portraying state and commercial interests as essentially monolithic.

While Beijing encourages and incentivises Chinese businesses to expand overseas, it has exerted relatively limited control over their activities in Africa (even for state-owned enterprises). Essentially, if a firm can get funding, they have largely been left free to pursue their own interests.

Rather than being geostrategic in nature, Chinese financing is thus primarily determined by the interplay between uncoordinated Chinese commercial interests and political and economic dynamics in recipient countries.

The debt trap narrative obscures the real reasons to be wary of Chinese financing

Conceptualising engagement through the debt-trap lens thus obscures the legitimate reasons to be wary of Chinese financing practices. Problems with Chinese-financed projects tend to arise for two main reasons.

Firstly, much Chinese lending is for large-scale projects, but 90% of all megaprojects go over budget no matter the location or manner of financing.

Secondly, most Chinese loan deals are made at the elite level with little transparency. While cost estimates for such projects are typically publicised, specific terms are not, and Chinese banks do not report cross-border financing in a systematic fashion.

Meanwhile, limited state supervision has resulted in a relatively unregulated lending environment. The combination of these factors can result in economically irrational projects with little oversight and poor environmental and social safeguards.

Geopolitical narrative

The debt-trap narrative has in part gained prominence due to its growing use by US officials to try to undermine Chinese influence in Africa. Washington warns that Chinese-funded development projects, in the words of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, are "almost certainly designed for foreclosure" (see US/AFRICA: Trump policy faces familiar hurdles - January 28, 2019).

The debt trap narrative is in part geopolitically motivated

Such rhetoric intensified ahead of the 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which saw Beijing pledge 60 billion dollars in development assistance to Africa through various channels over three years (see CHINA/AFRICA: Policy shift will be mainly symbolic - September 5, 2018).

The impact, however, is debatable. In 2018, as this narrative gained pace, several countries rejected or altered their Chinese loan deals. Concern over Chinese lending practices may have played a role, but domestic political and economic factors (largely around electoral transitions) appear more prominent.

For example, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Sierra Leone all cancelled large-scale Chinese-funded projects. However, a closer look reveals projects with tenuous economic logics or deals struck between opportunistic commercial actors and outgoing regimes, while other Chinese deals remained on the table (see SIERRA LEONE: China relationship will be reconfigured - October 24, 2018).

Changing the landscape

In Africa, Chinese lending is seen as an opportunity as much as a risk.

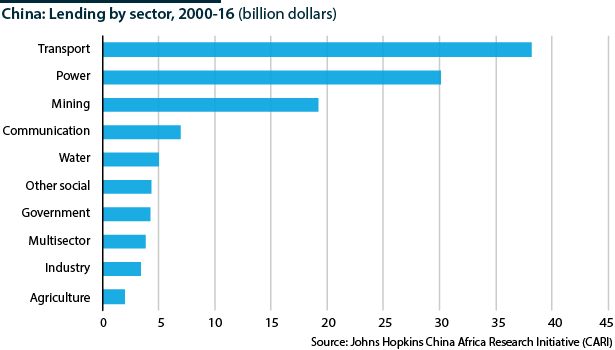

Africa faces an infrastructure deficit of approximately 130-170 billion dollars each year, with a financing gap of 68-108 billion dollars. This shortfall encompasses critical development infrastructure including transportation, energy generation and telecommunications (see AFRICA: Improved infrastructure will be key to growth - September 24, 2018).

Having neither the capital nor expertise to resolve this historically rooted deficit, African nations largely depend on external financing to build the infrastructure necessary for development.

Approximately half of Chinese financing in Africa goes towards such infrastructure projects, with much of the rest divided between extractive, commercial and information and communications technology projects.

Such projects are important to African leaders, both in terms of driving their industrialisation agendas and often in terms of their own personal agendas.

By characterising Chinese financing as part of a grand conspiracy perpetrated against African nations, the debt trap narrative thus largely ignores African agency in debt accumulation -- and the ultimate responsibility of African governments for good governance, environmental and social standards, and transparency.

Ultimately, Chinese financing presents both risks and opportunities for African states. How well risks are managed and opportunities leveraged will largely be a function of the extent to which African states themselves secure deals and manage projects responsibly for the benefit of their broader populaces.