World hunger is likely to rise as 2030 UN target nears

The world is far from meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goal to ‘end hunger’ by 2030

Updated: Apr 21, 2020

The number of people classed as 'hungry' increased to 821 million in 2018, from 811 million in 2017, and a low of 785 million in 2015, according to a recent report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). This continues a recent trend of a slow increase in global hunger since 2015, although the proportion of hungry people globally is largely unchanged (around 11%). The trend is being compounded by a rise in obesity and overweight.

What next

Global hunger is being driven by a complex interaction of multiple factors, especially economic growth prospects, climate shocks and distorted agrarian supply chains. Closer integration of nutrition policy and poverty alleviation efforts would make economic planning more ‘nutrition-sensitive’. However, structural constraints dim the prospects for reversing the trend of rising hunger.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Climate-sensitive agriculture will generate more interest as extreme weather events rise in intensity and frequency.

- Taxes on high-sugar, high-fat foods will rise, but without access to healthier options, the problem of poor nutrition is intractable.

- Governments will face pressure to increase investment in nutrition education to help people make healthier choices.

Analysis

UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 calls for ending hunger and ensuring access to "safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round" by 2030, as well as eradicating "all forms of malnutrition".

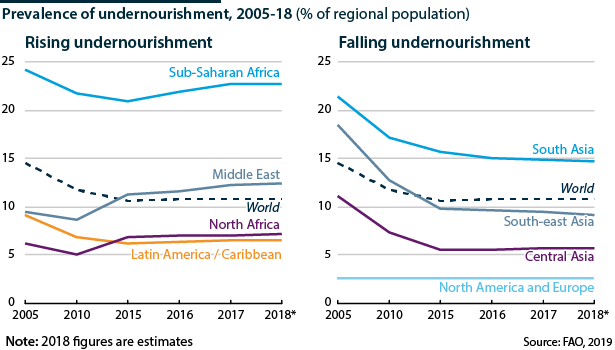

The FAO reports, however, that hunger has risen in many regions worldwide since 2015, the most pronounced increases occurring in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East:

- In sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 23% of the population is still classed as hungry (up 2 percentage points from 2015).

- In the Middle East, 12.4% of the population is hungry as a result of conflict (up from a low of 8.6% in 2010).

Moreover, progress is not happening at a sufficient pace to meet broader global nutrition targets, such as reducing the proportion of infants with low birthweight, infant stunting and food wastage.

Food insecurity

This year, the FAO has introduced a broader measure of the 'food insecurity experience' -- referring to situations where people do not face the extreme situation of hunger, but do not have regular access to sufficient and nutritious food.

Uncertainty about access and affordability leads to poor nutrition choices. This measure expands the number of those facing poor nutrition to 26% of the world's population, or around 2 billion people.

Complex drivers

Hunger is driven by complex economic factors

The FAO has stressed the connection between poor nutrition and the state of the world's economy.

Growth

Hunger and undernourishment are inversely correlated with economic growth. Hunger has risen particularly in countries whose economic growth has slowed or contracted:

- Burundi, Sudan and Zimbabwe were the three countries where economic shocks were found to be the primary causes of food crises in 2018.

- Undernourishment was already on the rise from about 2011, in countries facing economic downturns: 65 of 77 countries that have seen rises in hunger since 2011 have simultaneously suffered economic shocks.

Thus, while global hunger only began to rise in 2016, it had already been rising in countries experiencing economic downturns.

Commodity dependence

In the 65 countries where undernourishment occurred while the economy slowed, 52 are commodity-dependent either for food and fuel imports, or commodity exports.

Broader transformations such as diversification in commodity-dependent countries, is therefore important for reducing hunger and improving nutrition.

Social net

Such structural changes would have more significant effects on nutrition if accompanied by measures to reduce social inequalities and strengthen social protection systems (through universal healthcare or food vouchers, for example) to enable vulnerable groups to weather future downturns.

For instance, evidence shows that school feeding programmes improve access to nutritious and balanced meals for children, and serve as a form of social protection against household income shocks.

In addition, such programmes provide stable markets for local farmers, with spill-over effects: an estimate of Kenya's school feeding programme suggests that the programme has a multiplier effect of 2.74 on activity in the local economy.

However, governments frequently cut public spending during economic uncertainty, narrowing social protections. Reducing this vulnerability would require a commitment to counter-cyclical social spending -- or at the very least, a commitment to price stability for essential, high-nutrition food during a downturn to prevent households from switching to cheaper, processed food.

Climate change consequences

Climate change also threatens food security, as highlighted by a special August report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on the impact of climate change on land:

- The majority of the world's hungry (almost 600 million) live in countries with high exposure to climate shocks such as extreme rainfall, drought or temperature levels. Such shocks are increasing in frequency and intensity (see INTERNATIONAL: Rising emissions worsen disaster risks - June 12, 2019).

- Climate shocks also interact with the impact of economic downturns, with both shocks playing a role in 33 out of 53 countries that suffered food crises in 2018.

In the longer term, such risks are likely to rise owing to inadequate progress on addressing climate change. The IPCC report observes that animal growth rates and the productivity of pastoral systems in Africa have already fallen, as have crop yields in tropical regions thanks to higher temperatures.

Crop strains which are more resilient to variable temperatures or invasive pests that spread thanks to warmer weather may improve the resilience of food-production systems. These are not, however, permanent solutions in the face of rising global temperatures which are putting increasing strain on the productivity of agricultural land, and the greater likelihood of extreme weather events.

Obesity and overweight epidemic

$2tn

Estimated annual cost of obesity and overweight to the global economy

Simultaneously, poor nutrition-related problems are escalating globally.

Obesity and overweight are increasing in all age groups and in all countries; some 39% of the world's adult population (or 2 billion people) were classed as overweight in 2018, up from 31% in 2000 (see INT: Policy on ‘globesity’ epidemic needs rural focus - May 23, 2019).

The FAO report estimates that obesity and overweight cost the global economy 2 trillion dollars annually, largely from lost economic productivity, in addition to direct healthcare costs.

As with other aspects of nutrition, early-life influences shape subsequent adult risks for obesity and overweight (as well as other non-communicable diseases). Notably, poor maternal health -- including during the prenatal period -- increases the risk of overweight, making maternal health an area where effective nutrition intervention is vital.

For instance, some countries have begun actively supporting breastfeeding because of its contribution to early-years nutrition. Globally, 42% of infants are estimated to be exclusively breast-fed (up from 37% in 2012), but there is still some way to go to meet the 50% target by 2025.

In emerging countries such as Brazil, China, South Africa and Mexico, nutritious foods are more expensive than high-fat and high-sugar processed foods. Here, some fiscal measures could help combat obesity, such as sugar taxes.

However, other non-fiscal measures are also necessary, including ensuring the affordability of nutritious food, dietary guidelines and regulatory standards, in order to facilitate healthier diets especially within schools.

Outlook

Targeted and multi-pronged policy interventions across the human lifecycle would improve nutrition, particularly among vulnerable groups. However, these efforts vary regionally, and are vulnerable to both economic and climate shocks. Moreover, given the tepid outlook for global growth for 2019 and 2020, the overall number of hungry people is likely to rise in coming years.