Turkish invasion of north-east Syria is a risky gambit

A Turkish incursion into north-eastern Syria, months in the planning, has begun but could provoke a major backlash

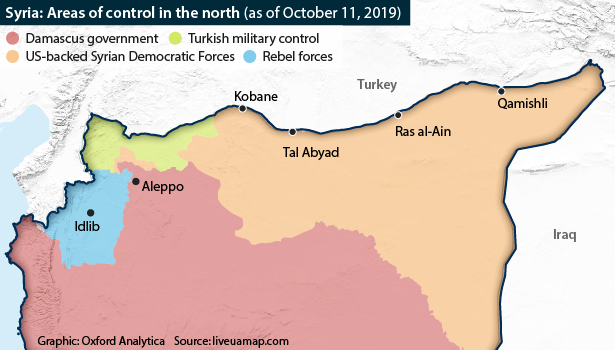

Turkey began a military incursion into north-eastern Syria on October 9, after US President Donald Trump said he would no longer impede Ankara’s plans. The offensive has, however, exacerbated Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan’s already-strained relations with the United States and EU. The longer fighting persists and the farther Turkey tries to penetrate, the higher the risk that the United States in particular will impose severe sanctions and send the Turkish economy deeper into recession. Although tensions between Washington and Ankara serve Moscow's interests, Russia too has no desire to see Turkey expand the area of Syria it already controls.

What next

The EU is expected to announce some measures against Turkey at its summit on October 17-18. More ominously for Erdogan, there is growing bipartisan support in Washington for economic sanctions against Turkey if it persists with its operations against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). It is unclear how Trump will react, although he has threatened Erdogan with economic consequences should Turkey cross unspecified red lines. Republican opposition to Trump’s policy shift was so strong that sanctions may have the necessary two-thirds majority to overcome any presidential veto. If the fighting continues -- or intensifies -- the pressure on Trump to agree to sanctions is likely to become irresistible.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The incursion has fuelled nationalist fervour inside Turkey and, in the short term at least, boosted Erdogan’s previously fading popularity.

- Yet it will not alleviate social tensions by providing a solution to the continued presence of so many Syrian refugees.

- US sanctions in particular would trigger a run on the Turkish lira.

- The international outrage over the incursion has made the PKK less likely to launch a bombing campaign inside Turkey.

- Such a respite may be short lived if international condemnations of Turkey are not followed by concrete measures.

Analysis

The Turkish incursion into north-eastern Syria against the Kurdish-led SDF, which had been fighting alongside US troops against Islamic State, came three days after Trump tweeted that Washington would not attempt to prevent a Turkish invasion, in an apparent reversal of previous US commitments to the SDF (see SYRIA/TURKEY: Talks over ‘safe zone’ will drag on - September 6, 2019).

The operation itself was, however, months in the planning. Over the summer, Turkey amassed an invasion force on the border opposite the area controlled by the SDF -- which Kurds refer to as Rojava -- while Erdogan repeatedly threatened to launch a unilateral offensive unless Washington bowed to his demands for a 'safe zone', some 450 kilometres wide by 30 kilometres deep.

The strip of land would be cleared of Kurdish armed groups and administered by Turkey; Ankara would relocate to it 1-2 million of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees estimated to be in Turkey.

Security threat?

Erdogan has attempted to justify his incursion on the grounds that the SDF's control of Rojava poses a threat to Turkey's security. This is misleading.

Kurdish forces have never attempted to attack Turkey from the area

Although the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) that dominate the SDF are affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which has been waging an insurgency for Kurdish rights in Turkey since 1984, they have never attempted to attack Turkey from Rojava. The PKK's own insurgency has long been based out of northern Iraq rather than Syria.

However, the mountainous terrain in northern Iraq makes it very difficult for Ankara to stage military operations there. In contrast, the terrain in northern Rojava is relatively flat, which makes it much easier for Turkey to deploy its overwhelming superiority in firepower, including artillery and armour, in an invasion.

However, this does not explain the timing of Turkey's latest incursion into Rojava, which has been under SDF control since 2015.

Domestic motivations

The timing of the operation appears to have been determined by Erdogan's domestic political considerations.

Military planning began in earnest after political setbacks in the summer

Although Ankara had long expressed its unease at the SDF's presence on its border, detailed planning for an incursion only appears to have begun earlier this year. It was in the summer -- after Erdogan had suffered humiliating defeats in local elections, particularly the June rerun of the Istanbul mayoral election (see TURKEY: Pressure is likely to build on opponents - August 16, 2019), and with opinion polls suggesting that his popularity was in irreversible decline -- that Turkish troops began massing on the border.

Recent history shows that Erdogan's popularity rises when he launches operations against perceived national security threats, such as the brutal internal military campaign against the PKK in 2015, mass purges of the state apparatus following the failed coup of 2016 and the seizure from the SDF of its Syrian enclave of Afrin in early 2018.

Opinion polls also suggest that the two main reasons for the decline in Erdogan's popularity are the current economic downturn and popular resentment at the presence of so many Syrian refugees (see MIDDLE EAST: Pressure over Syrian refugees will grow - August 29, 2019).

Poor prospects

There is little prospect of Erdogan ever realising his goals. There is no infrastructure to accommodate large numbers of refugees in his planned 'safe zone'. Nor is there any possibility of an external actor, such as the EU, paying to construct it. Turkey lacks the funds to do so itself.

It is also difficult to see why large numbers of the refugees in Turkey, only a tiny proportion of whom originally come from the area, could be persuaded to go to Rojava voluntarily. Meanwhile, a mass forced relocation would result in an international outcry.

Military difficulties

There are also questions about whether the Turkish military would eventually be able to seize and secure such a large area.

For the moment, battle plans are mainly focused on a 120-kilometre strip of territory between the Syrian border towns of Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ain. Turkish forces, including five brigades of regular troops and around 5,000 special forces, as well as 5,000 members of the Syrian National Army (a coalition of Islamist groups armed and equipped by Ankara) have crossed into Syria in rural areas.

Their initial goals appear to be to establish bases in the countryside, control the road that runs close to the border and encircle Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ain, before taking both towns and then pushing farther south.

Problematically, if the SDF does not retreat (it has vowed not to), any ensuing urban warfare will be very costly in terms of casualties and Turkey's already-battered international image. Indeed, flattening residential areas or high civilian loss of life would generate outrage, while gradual street-by-street fighting, would entail heavy casualties on the Turkish side.

Fighting intensity

Prior to the US policy reversal, Ankara and Washington had been engaged in a consultative process, where the United States tried to assuage Turkish pressure by persuading the SDF to dismantle defences and pull back from the border. As a result of measures previously undertaken, casualties and clashes have so far been relatively light.

Yet the fighting is expected to intensify as the SDF recovers from the initial shock and particularly if Turkey penetrates deeper and tries to take urban areas by force.

The SDF is no match for the Turkish military in pitched battle, but even if Turkey can seize a large area of territory, deployed troops would remain vulnerable to improvised explosive devices and hit-and-run attacks. Moreover, the longer the fighting persists and the deeper Turkey tries to penetrate, the higher the risk that it will be faced with international sanctions.