US deaths of despair will drag long-term growth lower

An uptick in US life expectancy does not signal an end to the 'deaths of despair'; the economic cost will only grow

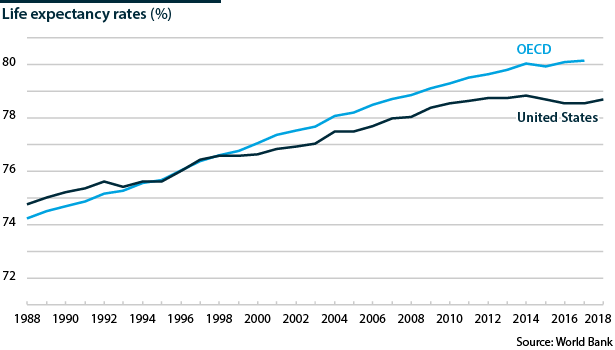

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on January 30 that US life expectancy at birth rose in 2018. This followed a decline in life expectancy in the years 2014 to 2017, caused by ‘deaths of despair’ among low-educated, white baby boomers, linked partly to escalating use of opioids. However, life expectancy and health for this segment of the population is not improving and their employment prospects are blighted by long-term economic restructuring and low labour mobility.

What next

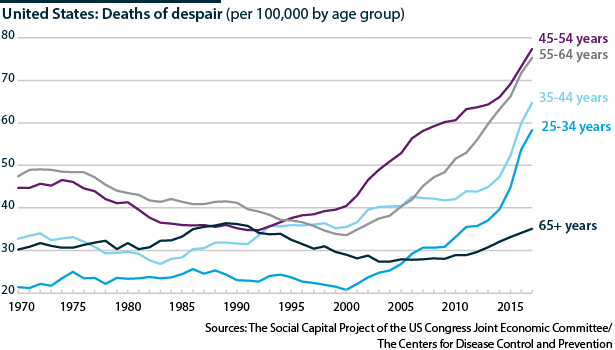

The rise in life expectancy in 2018 is likely to be a pause resulting from the crackdown on opioid prescriptions rather than a permanent shift. Suicide rates are at their highest since 1941, and death rates are flat for 55-64-year-olds when those for other cohorts are decreasing. The economic costs of this social crisis will surge. Differing opinions on root causation imply that policy responses will be piecemeal and may fail to address underlying factors, including labour market mobility and greater regional disparity in education and healthcare.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Anti-drug abuse policy will target synthetic opioids including fentanyl; these are a larger problem than natural and semi-synthetic opioids.

- Geographically targeted policies could create opportunities for workers with obsolete skills in places with scant job prospects.

- Geographically targeted policies have tended to be politically difficult to implement; the coming years will be no different.

- Generating low-skilled service jobs outside metropolitan areas will challenge labour policy in coming decades.

- Common root causes may drive deaths of despair higher in other nations, drawing more attention to well-being as a gauge of economic growth.

Analysis

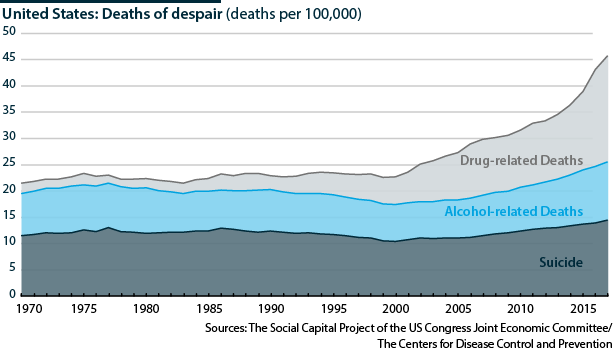

US 'deaths of despair' refer to deaths among low-income, less than college-educated, middle-aged whites from drug overdoses, suicide and alcohol abuse-related disease. In 2002, 48.5 non-Hispanic whites aged 45-54 per 100,000 died a death of despair, surpassing the previous peak in 1975. By 2017, the figure had risen to 91.6. They account for more than 100,000 preventable deaths a year, mainly male, and rank as the seventh-likeliest cause of death.

The rise in mortality (death) and morbidity (disease and ill-health) rates among this group from 1999 to 2015 contrasts with falling rates in other industrialised economies and US age and ethnic groups. Princeton University's Anne Case and Angus Deaton identified this phenomenon in 2015, since when the mortality and morbidity rates of this group have continued to rise.

The increase has more than offset other improving health outcomes including falling cancer death rates. US life expectancy at birth fell in the four years to 2017. Life expectancy rose in 2018, driven by a fall in opioid- and heroin-related overdose deaths, but the death rate for 55-64-year-olds was little changed in 2018. Preliminary data for January-June 2019 suggest that the decline in overdose deaths has, at best, flattened.

Geography

Deaths of despair have spread up the eastern heartlands through the Appalachian coalfields and the Ohio River Valley industrial rust belt. Low-income, non-metropolitan counties have been hardest hit -- particularly those that became poorer between 2000 and 2015 after manufacturing employment collapsed in many rural areas and small towns and cities. Life expectancy was equal for metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas in 1980 but has subsequently diverged, especially since 2000.

Opioids

The opioid crisis is amplifying the deaths of despair. The late Princeton economist Alan Krueger estimated in 2017 that half of the men who are out of the workforce were taking pain medication -- two-thirds a prescription painkiller, such as an opioid.

Some researchers argue that this is a consequence of globalisation and technological change dislocating US blue-collar jobs. They point to the correlation between median real household income per person and mortality since 1980, and to the rising share of men of prime working age (25-54 years old) who have dropped out of the workforce -- one in seven, against one in 25 in 1950, and currently one in five without a college degree.

Others, including Case and Deaton, suggest that this is only part of the explanation. The correlations weaken when disaggregated by age, income and race. They argue that deaths of despair are the cumulative effect of economic and social disadvantages for those with less than a college degree, causing a generation-to-generation downward spiral. More than 50% of those aged 25-54 years without a college degree in 2018.

Policy responses

The labour-market explanation encourages a solution that would narrow post-employment incomes via welfare payments or a guaranteed minimum income. Some Democratic presidential hopefuls propose this. The president has focused on trade and immigration policy to try to restore 'lost' blue-collar jobs.

The broader explanation requires a complex policy response to tackle the decline in blue-collar identity and purpose that resulted from the loss of jobs and the community ties that came with them (see UNITED STATES: Policy can bolster inflexible places - February 25, 2019). This could not be assured of support continuing from administration-to-administration at federal or state level.

Another approach is prioritising single-issue federal targets such as tackling opioid demand and supply (which the Trump administration is doing), improving the safety net for mothers and children (which it is not) or bolstering mental health services (whose federal funding faces cuts).

Small-scale experiments are creating informal safety nets by providing access to volunteering and other community activities to minimise the isolation of those not working. Use of public-private partnerships is also growing locally to support schemes to repair civic structures, provide reskilling and create jobs (see UNITED STATES: Amazon-NYC reversal will aid PPPs - April 2, 2019).

Economic impact

Healthcare, criminal justice and workplace costs associated with just the opioid crisis rose to an estimated 75 billion dollars in 2016 from 12 billion in 2001, according to a study published by Penn State University in July 2019.

$696bn

The estimated cost of the opioid epidemic in 2018

In 2017, the White House Council of Economic Advisors put the figure much higher, at 504 billion-622 billion dollars for 2015, accounting additionally for the full value of lives lost, assuming opioid-related deaths were under-reported and including deaths related to illicit as well as prescription drug abuse. In October 2019, the same organisation estimated the 2018 cost at 696 billion dollars.

Taxpayers shoulder most of those costs through Medicaid, the federal and state health insurance programme for those on low incomes. One in three opioid addicts is treated under Medicaid, which foots the bill for one-quarter of substance abuse treatment reimbursed by insurance. The Penn State researchers estimated that the additional annual burden on Medicaid topped 8 billion dollars by 2013. It will only have grown since.

Cutting emergency departments' opioid prescriptions to Medicaid beneficiaries (who are up to twice as likely to be substance abusers than the privately insured) has significantly reduced the epidemic on the demand side. Opioid oversupply has become a legal issue for opioid firms (see UNITED STATES: Opioid firms face criminal liability - December 2, 2019).

Prenatal exposure to opioids adds an estimated 1.5 billion dollars a year to the hospital costs of newborns. The future burden of lifelong poorer health outcomes for these children is unquantifiable.

Rising numbers of newborns are exposed to opioids prenatally; healthcare costs of this could surge

Outlook

The deaths of despair are rooted in the decline of the traditional blue-collar working class, the erosion of families and communities, declining labour mobility and inadequate public healthcare, especially outside the major cities. This will spill over to future generations.

Indeed, researchers at Vanderbilt University note a rise in deaths of despair among those in their late 30s and early 40s across all ethnicities, implying that the crisis in low-educated, white baby boomers may affect Generation X-ers (aged 40-55) in years to come.