More concentration, less dynamism may dampen US growth

Recent research shows that US business concentration reduces dynamism, lending credibility to calls for more competition

US business concentration has risen since the 1990s, accompanied by higher profit margins, weaker investment and labour accounting for a lower share of income. Research finds that having fewer new firms entering industry is reducing business dynamism and workers’ geographic and sectoral mobility, as well as making it easier for less productive firms to stay in business. In Europe, competition policy is more vigorous and business concentration is lower -- but neither business dynamism nor productivity is notably higher than in the United States.

What next

The perception of greater concentration and its negative effects is spreading among economists and politicians. While the research findings are open to alternative interpretations, they all point to the likelihood of a less vibrant US economy ahead. Calls for anti-monopoly policies to be revived herald the end of a deliberately relaxed approach to corporate power over the last 30 years. While the EU’s more vigorous competition policy will be an example and stimulus for the United States, policymakers there and in Europe will also explore other ways of boosting productivity and enhancing the business environment.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The benefits that the largest tech firms have produced, such as job creation and tech innovations, have muted criticism of their practices.

- The giant tech firms that have branched out into other sectors will be targets for breakup and other anti-monopoly actions.

- The EU is pressing for digital firms’ sales to be taxed in the country of sale; this could help EU firms compete with larger US ones.

Analysis

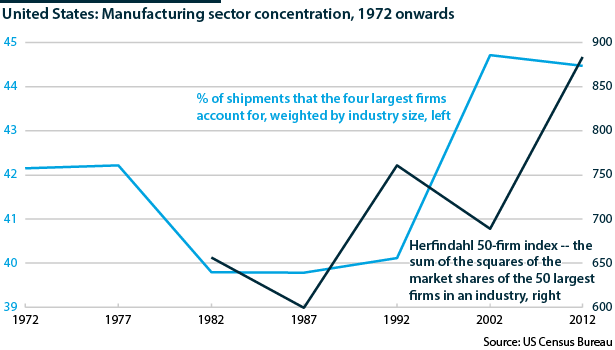

Economists across different specialties are finding that US product markets are becoming more concentrated, dominated by a few large firms (see INTERNATIONAL: Investment faces a multitude of risks - April 4, 2019). The average US firm is now almost three times larger in real terms than it was 20 years ago.

This has driven a systematic increase in industry concentration. Three-quarters of US industries have become more concentrated over the past 20 years. Most measures of concentration hit low points in the 1990s and rose thereafter. This pattern holds across different industries and gauges of company scale such as value-added, shipments and employees.

Concentration rose for several decades in the United States without interference from regulatory authorities because the larger firms and more concentrated industries were the sources of popular products and services that fostered rising productivity, incomes and profits. Falling prices and improved features drove demand, contributing to firm expansion, which in turn generated scale economies that further lowered costs (see INTERNATIONAL: Firms can aid equality and productivity - September 11, 2018).

More ominously, though, the increasingly large scale of the successful companies raised the entry price for potential competitors. Successful companies became entrenched companies. An analytical and policy problem is to distinguish good concentration, in which high price elasticity and scale economies drive down prices and raise productivity, from bad concentration, in which high fixed costs create entry barriers, reduce competitive pressures, and lead to higher prices and a loss of dynamism.

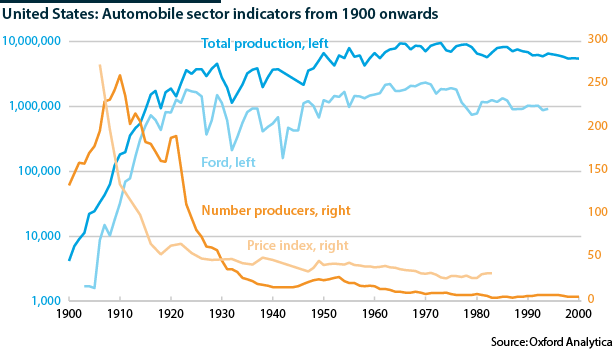

US autos -- good concentration to bad

The US automobile sector offers an example of an industry evolving from good to bad concentration. In the early 1900s, almost any competent machinist could produce a car, and hundreds tried. In 1920, almost 200 companies were active, the survivors of 1,000-plus entrants. Prices, adjusted for quality and inflation, fell by more than four-fifths between 1905 and 1930 while the scale of output at the largest company jumped from single digits to more than 1 million cars per year.

Scale economies and high capital entry costs then pushed down the number of surviving companies in the 1930s to a handful of firms that dominated the industry. Price declines decelerated and then stopped. The post-1945 oligopoly of three major companies caused the industry to lose competence, and indeed almost disappear, when confronted by cheaper, higher quality European and Japanese competition in the 1970s.

There were just three US car producers in the decades post-1945, from 200 in 1920

Good concentration to bad since 2000

Higher concentration was correlated with rising productivity, falling prices and high investment rates until 2000.

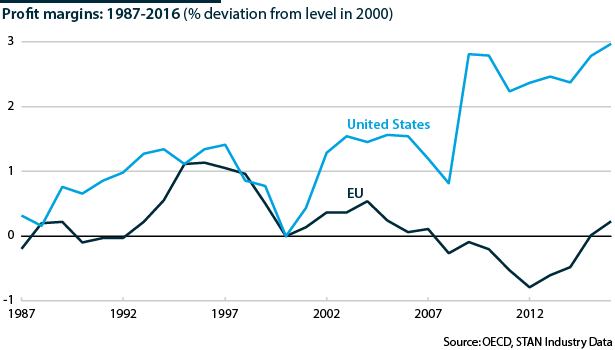

The relationships have reversed this century and rising barriers to competition are the most plausible explanation for this. Research by economists at New York University (NYU) in September 2019 found high entry costs to be a main source of market power, leading to higher markups and a lower share of income going to labour than capital.

The rise of concentration found in the United States, however, is not seen in Europe, nor is the increase in profits.

The uniqueness of the US trend suggests that technology cannot be an explanation for high concentration and its consequences (see UNITED STATES: Deaths of despair will drag GDP lower - February 6, 2020). The NYU economists argue that the rise of market barriers in the United States compared to Europe is partly explained by weakened competition policy, accompanied and driven by more intense business lobbying and political contributions.

The land of free entry

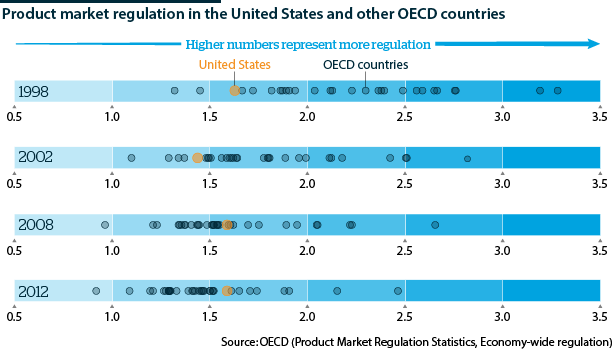

For more than a century, US markets were freer and more competitive than those in other nations. The United States invented modern antitrust in the late 19th and early 20th century and later led the deregulation of airlines and telecommunications.

Europe, heeding the advice of policymakers and academic economists, established an independent antitrust regulator and systematically deregulated many markets. According to many measures, European markets are now more competitive than their US counterparts.

Passenger airlines is an example of a US sector that used to be highly competitive. However, regulators then allowed a wave of mergers -- Delta-Northwest in 2008, United-Continental in 2010, Southwest-AirTran in 2011 and American-US Airways in 2014. Europe, in contrast, removed barriers to entry and saw some smaller low-cost airlines thrive. Deep discounters account for around one-third of the market in Europe, but less than 10% in the United States.

Deep discounters account for 33% of European aviation and less than 10% of US aviation

Decline of business dynamism

According to several measures, the US economy has become less dynamic since 2000. For example, the startup rate of new firms fell by 15% from the 1980s to 2010 in all major sectors; in high-tech, the startup rate only began to decline in the post-2000 period.

In 2014 economists at the University of Maryland conducted a study of entrepreneurship using US Census Bureau statistics on business dynamics from 1976 to 2011 and found that incentives to start new businesses are declining in all sectors.

Productivity improvements depend not only on technology but also on allocative efficiency -- resources continually moving from less to more productive firms. Declines in allocative efficiency emanating from declining entry and exit rates accounts for the bulk of the slowdown in productivity from the 1990s to the 2000s. Barriers to entry, the dominance of large incumbents and growing concentration all point to worrying changes in the US business environment.

While US evidence is mounting that market concentration eventually dampens business dynamism, implying that increasing competition would be likely to boost entrepreneurship and possibly productivity, there is little evidence that the less concentrated EU has seen markedly higher dynamism or productivity. The EU and United States are likely to explore different policies to try and increase their dynamism and productivity.