COVID-19 vaccine allocation may change over time

The top US infectious diseases expert said that a COVID-19 vaccine may be available to US nationals by late December

Dr Anthony Fauci, the Director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said yesterday that there could be a vaccine deployed to immunise high-risk US nationals as early as December or early January. Although COVID-19 vaccine candidates are already in production to speed up delivery, there will be limited doses of vaccines available in the immediate term if one of the eleven candidates currently in last phase clinical trials receives authorisation. Who is vaccinated will not only affect the speed in which this pandemic is brought under control, but also which communities suffer the largest socioeconomic and health scars from it.

What next

Rich nations have already pre-ordered multiple vaccine candidates and will be able to use them first. However, over the next twelve months at least, doses will be insufficient to prevent community transmission: it is estimated two-thirds of the population would need to be vaccinated to achieve this. Health workers and individuals at greatest risk of death will probably be prioritised. From there, the order in which other groups with be vaccinated will depend on the particular characteristics of each country’s pandemic, and the priorities and governance of the specific country.

Subsidiary Impacts

- International actors such as Gavi and CEPI will try to ensure equitable distribution of vaccines across borders.

- Priority may be based on particular groups’ exposure to the disease, importance to society or economy and political power.

- Universal vaccine coverage will take many years and require prolonged international collaboration.

Analysis

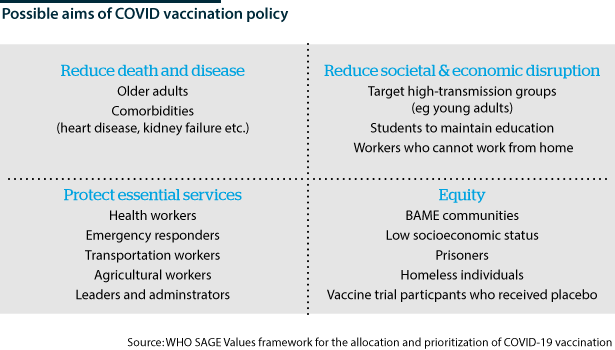

Prioritising those that most need a vaccine may appear a simple task. However, it is a difficult moral, economic and societal question.

There are two main objectives:

- interrupt transmission and control the pandemic; and

- protect high-risk individuals.

Vaccinating those with higher mortality and morbidity rates would reduce the extent of death and disease. In the case of COVID-19, the most obvious groups are the elderly and those with multiple high-risk comorbidities (such as diabetes, heart or kidney disease).

The pandemic has exacerbated existing structural health inequalities

However, historically marginalised groups and ethnic and impoverished communities have experienced disproportionately high death rates and economic impacts from COVID-19 and societies' response to it. There are calls to try to use vaccine policy to attempt to correct these injustices (see INTERNATIONAL: Coming months to be pandemic's riskiest - July 30, 2020).

Another consideration for limited supplies is immunising health workers first. That would sustain a critical service and reduce overall rates of transmission. However, it leads to the question of maintaining other key societal functions and vaccinating others such as the police, teachers, agricultural and transport workers.

Lastly, another priority population would be those people who are more likely to be exposed and spread the virus. This would include people who could be exposed to super-spreader events or adults in densely populated areas, for example.

A US stance

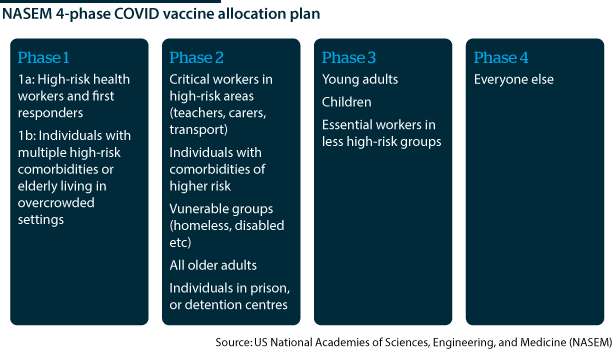

In the United States, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has tried to acknowledge all of these issues with a four-phase plan for the US population.

The first phase (1a) would vaccinate approximately 5% of the US population and concentrates on high-risk health workers. Phase 1b concentrates on reducing disease and death by vaccinating those at most risk of poor outcomes (10% of the US population).

A similar approach is followed in phase 2: vaccinating other at-risk groups but also trying to protect important societal functions, such as education and transport (30-35% of the US population).

Phase 3 is a more targeted approach aimed at reducing community transmission by vaccinating those at high risk of transmission but with likely milder disease (40% of the US population). It is only in phase 4 that 'herd immunity' would be approached by vaccinating the rest of the population.

The UK approach

The UK government stated that its principle aims are to reduce mortality, reduce serious disease and protect the National Health Service (NHS) and social care system. Perhaps in response to the disproportionate number of COVID-19 deaths occurring among elderly care home residents in the United Kingdom, the government has prioritised this group and their carers, as the first to be vaccinated.

Older cohorts and health workers will likely be prioritised

Subsequent vaccination would be of health workers and those over 80 and then in descending order of age until 50 years unless otherwise at high risk. There are no plans to vaccinate those under 18, who see few COVID-19 complications. There is acknowledgement of the need to get good coverage in minority ethnic communities; public health experts have called for clearer prioritisation of these groups, for instance, with lower age thresholds.

Vaccine variable

All plans will need to be flexible so they can be modified depending on vaccine effectiveness. The UK government acknowledges their plan assumes a vaccine that is effective in all age groups. However, any successful vaccine is likely to be more effective in certain populations.

Plans may vary according to vaccine effectiveness

Typically, immune responses among older people are less effective, requiring, for example, booster shots for effective protection (see INTERNATIONAL: Immunity will shape pandemic's future - June 26, 2020). This could complicate distribution of the vaccine and lead to lower protection if people forget or refuse the booster dose. Many of the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates are two-dose vaccines.

If a first vaccine is not very effective among older people (regardless of booster shots), then governments may focus limited vaccine supplies on younger age groups in order to create protection around the older, more vulnerable cohorts. In that case, for example, health workers, care home workers, physiotherapists, residential care staff and support staff who come into regular contact with elderly people may be prioritised.

It is unlikely that initial vaccines will prevent all infections, but they will still be useful if they limit severe disease and transmission. Studies on animals for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine candidate showed prevention of severe lung disease, but the subjects still exhibited mild symptoms. This could mean that some transmission may still happen, but it is assumed this will be lower than for non-vaccinated adults who get infected.

Immunisation tactics

In vaccine efforts against polio, a 'mop-up' strategy is used where vaccine efforts are concentrated in areas of local outbreak to try to break the transmission. This potentially could be used in response to COVID-19 where governments focus vaccination efforts on specific towns or cities. Although not equitable, this may bring about faster control of the pandemic in countries with regional outbreaks.

Another strategy is 'ring vaccination', whereby individuals who were or may have been exposed to an infected individual are identified and vaccinated, and then a second 'ring' of people who may have been exposed to the first 'ring' are vaccinated.

The US, UK and EU governments have produced broadly similar plans, but these will have to adapt depending on how effective an eventual vaccine is in different groups, the quantities available and logistical considerations, as well as the particular nature of the disease outbreaks in their populations (see INT: COVID vaccine roll-out will face multiple hurdles - October 14, 2020).