Global COVID vaccine roll-out will face many hurdles

With results due to be released by the end of the year, a vaccine is likely to be ready for distribution by early 2021

A dozen COVID-19 vaccines are in advanced trials across different countries. Initial data are expected to become available before the end of the year, and subject to evidence of safety and efficacy, to be submitted for approval and fast-tracked so that a vaccine is released within the first quarter of 2021. However, there are challenges to distribution worldwide. Diplomacy and logistics will eventually decide whether a vaccine serves the global population or not.

What next

More than one vaccine is likely to become available for limited use in the next few months. In the absence of a unanimous commitment on global distribution, countries may depend on bilateral agreements to procure vaccines, based on regional availability and distribution capacity. Countries may also set different priorities on whom to vaccinate first as supplies will be limited at least in 2021. Protecting only a proportion of the population will not stop the pandemic but will reduce COVID-19-related mortality.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Bilateral agreements between rich countries and vaccine manufacturers will result in unequal access to vaccines overall.

- Efforts to uphold scientific rigour will be important to maintain faith in science and the pharmaceutical sector.

- Vaccine scepticism and choice may affect uptake and coverage in some developed countries.

- Immunisation schedules for other infections may be disrupted to channel resources into distributing COVID-19 vaccines worldwide.

- Public health agencies may need restructuring and greater involvement from experts to rebuild trust in their decision-making powers.

Analysis

Vaccines are exceptionally highly regulated biological drugs requiring vast, demonstrable evidence of benefit with minimal and insignificant adverse effects, ideally none. This is because once licensed, vaccines are administered to billions of healthy people, as opposed to therapeutic drugs that are administered specifically to unwell patients.

Regulation and licensing

The licensing process for vaccines can happen in the country of use (with established regulatory authorities) or in the country of manufacture, followed by review and approval in the country of use. UN agencies purchase products that are pre-qualified by the World Health Organization (WHO), which in turn relies on licensing by an approved body.

Phase II/III clinical trials for multiple COVID-19 vaccines are expected to yield initial data by the end of 2020 (see INT: Vaccine timelines should be clear by end of 2020 - September 22, 2020).

There are some 250 vaccine candidates in development worldwide. Taking historical success rates into consideration, McKinsey estimates that seven to nine COVID-19 vaccines may be successful in trials -- this could rise to 20 in optimistic scenarios.

7-9

COVID-19 successful vaccines are likely to emerge

Regulatory bodies are prepared to expedite the review and licensing of a vaccine, once satisfactory safety and acceptable efficacy is shown (safety is non-negotiable). The European Medicines Agency, for example, uses real-time reviews of COVID-19 vaccines to speed up the process. Reviewing data in real time allows the regulatory body to reach conclusions about the efficacy and safety of the vaccines as data accumulate, before waiting for trials to conclude or reach predetermined points (typically, when a regulator would agree to review data).

The more effective a vaccine, the faster evidence that it works becomes clear. With tens of thousands of participants in the Phase III trials and a full-blown pandemic, these data points are likely to accrue quickly.

Safety is paramount, especially in the context of a rising vaccine hesitancy movement amid an ongoing pandemic (see INTERNATIONAL: Anti-vaxxers may derail virus control - May 21, 2020).

In an effort to highlight vaccine safety records, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) strengthened its guidelines on COVID-19 vaccines in October. It now requires trials to have two months of safety data on at least half of their Phase III study participants after a second dose of vaccination (if it is a two-dose regime) before applicants can seek an Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA). Most adverse events occur within two to three months after immunisation (see INT: New FDA rule aims to highlight vaccine safety - October 7, 2020).

The FDA has also specified that a vaccine considered for full licensing will have to demonstrate at least 50% reduction in disease in the test group and safety data spanning at least one year, shown in 3,000 vaccinated persons. Most early-roll-out vaccines will probably be licensed under types of EUAs.

Most early vaccines will be licensed under EUAs

Less than ideal efficacy for first vaccines may be considered, and indeed this is likely. They will still be useful, as they would lower mortality -- even if they do not stop the spread of infection -- though some social distancing measures are likely to persist (see INTERNATIONAL: Early vaccine may keep some distancing - May 12, 2020).

Beyond the scientific hurdle of developing a good vaccine, its fast and efficient distribution on a global scale now requires unprecedented cooperation among manufacturers, governments, cargo operators and ground workers.

No vaccine has previously been administered worldwide at maximum capacity and in minimum time, making this one of the biggest diplomatic and logistical challenges encountered by any immunisation programmes.

Vaccine manufacture

The total vaccine market is currently valued at USD35bn (less than 3% of total pharmaceutical sales). While initial screening of candidates takes place in various academic labs across the world, an industrial partner usually becomes involved at later human trials.

Four multinational brands -- GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Merck and Pfizer -- through various mergers now hold 85% of market share. Global investment in COVID-19 vaccines so far is estimated at USD7bn.

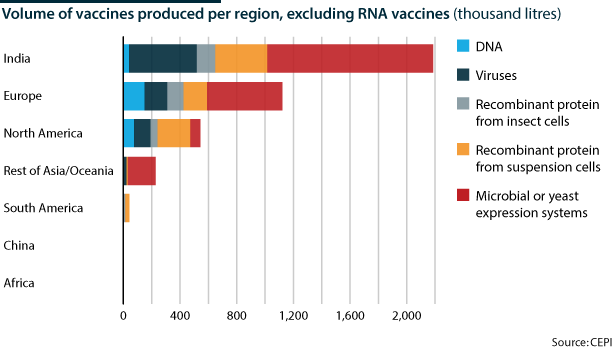

India, China and Europe have the largest capacity to produce vaccines, some of which are part of WHO/UNICEF's Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) against measles, polio, tetanus and others in developing countries. Newer vaccines such as those for hepatitis B, rotavirus, and haemophilus influenzae are less universally available because initial manufacturing capacity is limited and companies need a return on their R&D investment (estimated at USD1bn for each new vaccine) by selling to markets that can afford the high price.

In 2000, GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, was established as a public-private partnership to increase access to vaccines in developing countries through a system of incentives for manufacturers such as tiered pricing, advance market commitments, logistical support and innovative financing. In 2019, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was set up to work on vaccines for five priority diseases and also for emerging threats such as COVID-19.

Under the Sustainable Manufacturing Project, CEPI conducted a survey of vaccine production capacity involving 113 manufacturers from 30 countries. It found that 2-4 billion doses of a COVID-19 vaccine could be supplied by the end of 2021 (catering for 20% of the world population) without compromising other pipelines.

Besides initial stock, other factors that can affect the distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine include manufacturing speed, stability of vaccine product (ie, sensitivity to heat, light, radiation, environment changes or interaction with other vaccine components), cold chain considerations and uptake willingness.

Equitable distribution?

Historically, access to vaccines and therapeutics has not been equitable. International access to smallpox and polio vaccines, as well as HIV drugs, followed only after high-income countries had procured sufficient supplies.

In 2007, Indonesia opposed the idea of high-income countries using samples from affected regions and producing expensive therapeutics that the country of origin often could not afford. It evoked the right to 'viral sovereignty' where countries could refuse to share genetic information on pathogens unless granted equity in the diagnostics and therapeutics arising from that information.

Because of the ubiquitous nature of SARS-CoV-2, no country has such leverage for COVID-19. Countries do, however, have very diverse levels of wealth, and this could result in extreme discrepancies in protection from COVID-19.

Many countries have already secured millions of doses of one or more vaccines through bilateral agreements with manufacturers (see INT: Vaccine nationalism may prolong pandemic - September 2, 2020).

The United Kingdom, United States and Canada have the richest vaccine portfolio while the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine candidate has the most diverse purchase agreements, becoming the candidate that is projected to help the most regions of the world, aided by its low cost.

Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines are pitched at a much higher price and have higher stakes from affluent countries. Countries have also expressed an interest in the Russian Sputnik V vaccine as well as the Chinese Sinovac candidate. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation estimates that while 33% of COVID-19 deaths can be averted by selling vaccines to high-income countries, this number becomes 61% with equitable access.

A more inclusive vaccine initiative is the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX), currently a WHO/GAVI-led multilateral arrangement for pooled vaccine access. Eighty self-financing countries have signed up to the COVAX facility so far, in either committed or optional purchase agreements (which are hedged by differential pricing), while 92 participating low-income countries will be eligible to benefit from the COVAX Advanced Market Commitment (AMC) which depends on funding through sovereign donors, private sector and philanthropy.

COVAX AMC has so far been able to raise one-third of the total proposed funds of USD2bn. COVAX aims to provide doses for an initial 3% priority vaccinees in each member country, and increase this to 20% by the end of 2021.

Alternative allocation models have been suggested, based on risk (health care workers and older people) and 'Fair Priority' with staggered phases focused on:

- preventing premature death;

- sparing poverty; and

- transmission, but eventually leading to maximum coverage (above 70%).

Some large economies (Russia, United States) have refused to be part of the COVAX facility, choosing instead their own vaccine programmes or direct purchase of vaccines. China joined in early October. While China and Russia have each approved a vaccine for in-country limited use, few data have emerged from their trials (see CHINA/RUSSIA: Tactics will undercut vaccine take-up - October 1, 2020).

Logistical challenge

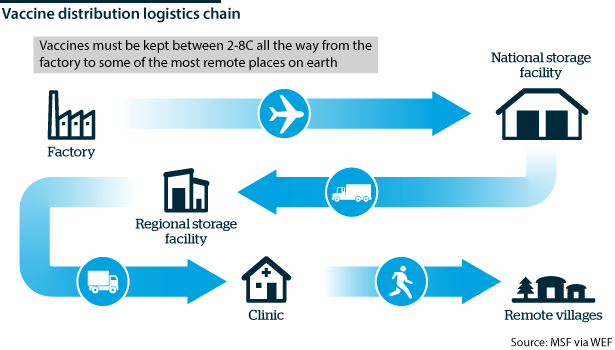

Once vaccine distribution is decided on paper, a significant hurdle is the actual transport and delivery of vaccines, most of which require cold storage or freezer support.

8,000

cargo aircraft estimated to be needed to supply a single vaccine dose worldwide

The International Air Transport Association estimates that 8,000 cargo aircraft will be needed to supply a single dose of a vaccine for the world's population. However, it is the vaccine's journey beyond the aircraft that is most vulnerable in areas without a reliable power supply.

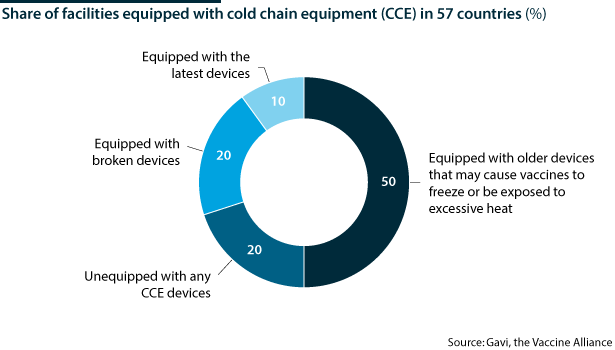

The WHO estimates that more than 50% of the world's vaccines go to waste for this reason. This is something the world cannot afford with the COVID-19 vaccine in short supply and where the nature and stability of the vaccine will be extremely important.

While mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid) vaccines, for instance those developed by Modern and Pfizer, require storage at between minus 24 to minus 80 degrees Celsius in specialised freezers, most other vaccines (those of Astra Zeneca and Johnson & Johnson, for example) are less unstable and need to be stored at minus 20 degrees Celsius, with temporary stability at between 4 and 8 degrees Celsius.

An estimate from DHL showed that only 2.5 billion people in 25 developed countries can benefit from frozen vaccines, compared with 5 billion people if using cold vaccines.

Future considerations

Vaccine manufacturers at this stage will need to prepare for post-pandemic scenarios where different vaccines may be needed as the dynamics evolve.

For example, dosage and immunisation regimes have not yet been determined. The level of vaccine dose needed to elicit an immune response that is enough to prevent severe disease or contracting COVID-19 is not yet known. This also means it is unclear whether one or two doses of a vaccine are needed -- twin doses have been eliciting stronger immune responses and may be needed for older people whose immune systems are weaker (see INTERNATIONAL: Immunity will shape pandemic's future - June 26, 2020).

Ideally, platforms developed at this time will be flexible and cater to changing requirements and potential future outbreaks. Vaccine demand may also be affected negatively by better drugs that reduce mortality -- especially if vaccines are only partially effective.

A unique characteristic of immunisation is the sheer scale of what is needed to protect populations fully, exacerbated by the complexities of a ubiquitous pathogen. To eradicate the virus completely, very high levels of induced population immunity are needed (over 70%), depending on the efficacy of a vaccine and other interventions. If the vaccine in use has sub-optimal efficacy, this coverage threshold may be even higher.

Low population-level vaccine effectiveness would make COVID-19 endemic

For this reason, maintaining trust in vaccines is of utmost importance. If vaccine coverage is patchy or insufficient, the disease is very likely to become endemic, either everywhere or in regions with low vaccination rates (as in the case of measles).

This has long-term repercussions for health, and also disproportionately affects economies. The IMF projected a loss of USD11tn from the global economy in 2020-21 and USD28tn over the period 2020-25, even with the USD18tn invested to tackle the pandemic. Other metrics on economic from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation show that extreme poverty has gone up by 7%, with 68 million people pushed below the poverty line this year.

Initial access to a vaccine ensures that at least a proportion of the population in each country will be immune. If this is the most vulnerable part, then the overall burden of disease will be significantly less. Because most of the population will still not have been exposed to COVID-19, virus transmission will continue, but with relatively fewer deaths.