Prospects for Russian politics in 2022

The Kremlin will consolidate political arrangements and practices, including repression, rather than make major changes

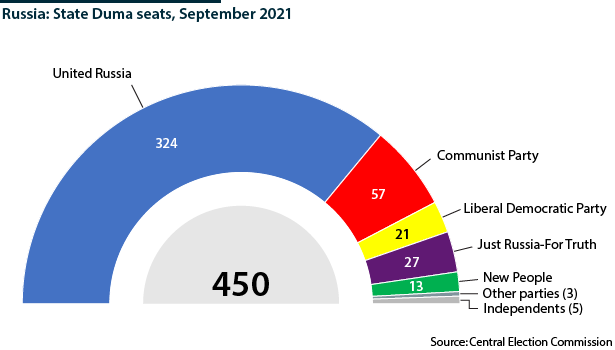

Now that the Kremlin has dealt with the immediate domestic policy priorities of constitutional change and parliamentary elections, 2022 will be a year of consolidation and continuity. The administration's focus will be on preparing what it regards as optimal, stable conditions for the presidential election in 2024. The Communist Party has a chance to build popularity among anti-government voters, but may not be bold enough given the Kremlin's limited tolerance for rebellious behaviour.

What next

Political stability, as envisioned by the Kremlin, is fairly well assured for the year ahead. The danger is that continuity becomes complacency and that no significant policy initiatives emerge next year. Failure to reverse poverty and curb COVID-19 will present real-world challenges which the government cannot afford to ignore if it wants stability at grassroots as well as elite level.

Strategic summary

- The Kremlin's attention will turn to managing the presidential election in 2024.

- Significant policy innovation is unlikely, creating risks of stagnation.

- The Kremlin will continue to suppress opposition activity, turning its attention to anti-government activity online and in wider society.

- Centralisation of governance will be enhanced, strengthening the Kremlin's ability to blame regional governors for policy failures.

Analysis

Over the last two years, the governance system under President Vladimir Putin has proved resilient to a series of challenges. It has carried out constitutional change and parliamentary elections, suppressed opposition challenges and maintained the loyalty of the elite.

The constitutional changes of 2020 cleared the way for Putin to stay in power beyond 2024. By removing the uncertainty that surrounded Putin's future, the Kremlin has cemented elite-level unity. After the carefully managed election of September, the political situation is unlikely to change over the next twelve months (see RUSSIA: Election meets sole aim of Kremlin validation - September 24, 2021).

The Kremlin is focused on extending Putin's rule beyond 2024 and has no desire for a radical shake-up; it will consolidate and strengthen systems that have served it well. With a strong aversion to risk-taking, it has in place the components it wants to be able to move towards a post-2024 Putin presidency.

Risk of losing momentum

The focus on political stability limits scope for significant policy innovation, and this presents risks if Russians see their incomes stagnating and no clear plan to reverse their fortunes (see RUSSIA: Welfare policies need change to cut poverty - October 20, 2021).

The ambitious National Projects first unveiled in 2018 lost focus last year when the government tried to channel funding to poorer people hit by the pandemic's fall-out. It may resume but the initial momentum has been lost (see RUSSIA: Development plan goes forward amid delays - December 15, 2020).

Growing public concern about inflation will shape economic policy. The government will maintain price controls on certain food products while the central bank raises its key rate to battle inflation (see RUSSIA: Food prices are a particular inflation worry - November 5, 2021 and see RUSSIA: Policy toolkit mixes rate rises and price caps - July 20, 2021).

Stability risks may stem from real-world problems, not political management

The government's action on the COVID-19 pandemic has been decidedly mixed: swift development of Russian vaccines was followed by a slow vaccination programme that faced widespread resistance. Restrictions have been extensive but still inadequate, and the scale of infections fatalities -- higher this month than a year ago -- has been aggravated by perceptions of a cover-up.

The response exposed a lack of unified policy formation at the centre of government. Decision-making was delegated to regional authorities as Putin tried to avoid blame. Until vaccination rates rise significantly, COVID-19 will present political and economic challenges well into 2022 (see RUSSIA: COVID rates surge after week-long holiday - November 8, 2021).

Removing sources of opposition

The Duma elections prompted an intensification of the campaign against political opposition in all its forms, and this is likely to continue throughout 2022.

New charges of 'extremism' are being prepared against imprisoned opposition leader Alexey Navalny, and another trial could take place in 2022.

Navalny's anti-corruption and electoral mobilisation networks have been shut down through judicial instruments (some specially designed) and plain persecution. The focus of repressions will widen beyond recognisable opposition groups to cover individuals engaged in any kind of criticism of the government (see RUSSIA: Repression grows despite regime stability - October 26, 2021).

Further measures to tighten control over the internet are likely. This will include greater efforts to coerce international tech firms. Government pressure forced Google and Apple to remove Navalny's 'smart voting' app when voting began in September.

The Communist Party's relatively strong performance in the Duma elections highlighted the continuing demand for political alternatives. However, opportunities for genuine opposition competition remain limited.

The Communists could be the 'new opposition' but may lack the courage

Strident voices within the Communist Party are likely to face government penalties and this will place the leadership in a difficult position, forced to choose between the safety of playing by the Kremlin's rules and the opportunity to appeal to an increasingly radical electorate (see RUSSIA: Communists may reduce United Russia lead - September 17, 2021).

Managed regional polls

The next test of opposition sentiment is the annual round of regional elections in September 2022, the most significant of which will be for Moscow city council. In the last contest for this council in 2019, the Communists won more votes than United Russia and their seat count increased.

This was partly the result of tactical voting by opposition voters, coordinated by Navalny's team. The introduction of electronic voting and elections held over three days reduced the effectiveness of smart voting in the 2021 elections, and the Kremlin is likely to adopt similar tactics next year.

Gubernatorial, assembly and municipal elections will take place across approximately 30 regions. This includes places where United Russia performed relatively poorly in this year's Duma election: gubernatorial elections will take place in five of the ten regions where the party scored its lowest vote share: Kirov, Yaroslavl, Karelia, Novgorod and Tomsk (see RUSSIA: No surprises in engineered elections - September 21, 2021).

These regional contests are unlikely to provide a focal point for protest action. If protests do happen, they are more likely to be of the government's (inadvertent) making, as happened with protests against pension reform in 2018 and demonstrations against the arrest of Khabarovsk governor Sergei Furgal in 2020 (see RUSSIA: Khabarovsk 'solution' is ill-judged - July 27, 2020).

Such mass action is unpredictable: it can occur spontaneously and does not require effective party organisation.

Eleven regions are scheduled to elect governors in 2022, but sitting governors have already been replaced elsewhere since September -- in Yaroslavl, Vladimir and Tambov -- suggesting that elections will be needed there, too. Established practice is for regional leaders to step down in good time to be replaced by interim appointees, who duly win election. The Vedomosti newspaper reports that early replacements are also likely in Krasnoyarsk, Saratov, Tomsk, Kirov and Ryazan (see RUSSIA: Kremlin picks governors to suit regional needs - May 6, 2021).

Downgrading regional power

Recent legislative proposals suggest that the Kremlin plans to tighten its control over regional governments, even though they are already in a weak and subordinate position.

Under proposed legislation, the president will gain more powers to dismiss and penalise regional leaders. The ability of voters to recall their regional leaders will be reduced.

Key regional heads will be allowed to stay on beyond two terms

The new law will remove term limits on regional leaders. This will enable the Kremlin to keep in place several key figures whose terms expire before 2024, including Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, as a way of maintaining regional-level stability through the presidential election period.

In Tatarstan, the bill is being opposed on the grounds that its strips the republic's leader of the unique title of 'president' and gives him and other governors the same status as 'heads' (see RUSSIA: Regional reform bill meets opposition - November 10, 2021 and see RUSSIA: Tatar leadership will contest status downgrade - October 27, 2021).