Algeria's Ghardaia violence may rise in the long term

The government's decision to send in the army is only a temporary solution

Violent clashes took place on July 8 in the oasis city of Ghardaia in the south of Algeria, between the region's two major communities, the Arabs and the Berbers. Clashes between the two groups have occurred sporadically since the 1970s. However, the most recent ones were the most violent so far: 23 people died and dozens were injured. The government deployed 8,000 troops in the city, but the escalating violence has raised concerns about the government's ability to resolve the conflict.

What next

The army can keep a lid on violent incidents in Ghardaia. However, without implementing sustainable policies to address the mainly economic grievances, clashes will probably recur once the military withdraws. Yet the probability that the government will promote development in the south is decreasing as Algiers' revenues dwindle with the fall in hydrocarbon prices. Without the power to appease citizens by providing housing or state jobs, the government could see levels of violence in Ghardaia escalate in the longer term.

Subsidiary Impacts

- More violence in Ghardaia would damage the government's reputation, undermining its ability to solve domestic crises.

- This would lead to a further loss of credibility at home and abroad.

- It could also cause concerns among oil investors, at a time when Algiers is looking to increase its hydrocarbons production.

Analysis

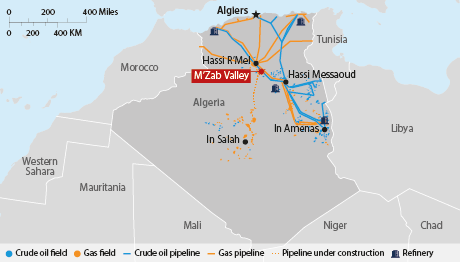

The M'zab valley consists of seven cities and lies about 600 kilometres south of Algiers. It includes a cluster of five in the south, Ghardaia, al-Atteuf, Melika, Bani Isguen and Bounoura, and two other more isolated communities, Berriane and Guerrara, further north.

Mozabite Berbers, who are Ibadi Muslims, have lived in the M'zab valley for centuries. The city of Ghardaia was founded in the eleventh century. The Arab community, who are Maliki Muslims, came later, while the (Arab) Chaamba tribe, which has seen the most frequent clashes, mostly arrived in the last 100 years.

The region is rich in natural resources, particularly oil and gas, and the development of the hydrocarbons sector has accelerated the rate of Arab migration from other parts of Algeria.

However, the local economy has not matched the growth of the hydrocarbons industry -- much like the rest of the country. High rates of unemployment -- especially among the youth -- housing and land shortages, high utility prices and cost of living in the valley mirror the situation elsewhere in Algeria.

Economic frustrations on the national level have magnified communal rivalries in the M'zab valley

In Ghardaia, competition for resources from the central state, such as social housing and jobs, has contributed to rising tensions between the Arab and Berber communities. Indeed, riots have repeatedly erupted following allocation of state-subsidised housing, with both communities accusing each other of receiving special treatment.

Berbers believe that the government favours Arabs in employment and housing, while Arabs think that Berbers are wealthier and exclude Arabs from their business activities intentionally. Berbers dominate business and trade links.

Informal economy

Ghardaia's location at the northern edge of the Sahara desert make it an important crossing point for trans-Saharan trade, particularly drug-trafficking routes from Morocco to Europe. The area's informal economy also provides an important source of income for the local population and jihadi groups in the Sahara and Sahel (see WEST AFRICA: Sahel dynamics foster illicit economies - July 31, 2015).

Jihadi threat

The upheaval that followed the Arab uprisings encouraged the proliferation of such groups in North Africa, the Sahara-Sahel region and even Algeria itself, where a group of armed men beheaded a French national in September 2014 shortly after they declared their allegiance to the Islamic State group (ISG).

Several jihadi groups operate in the Sahara-Sahel region: Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Al Mourabitun, Ansar Dine, Ansar Al-Sharia, the Movement for the Unity and Jihad in West Africa and sympathiser groups that have pledged to ISG.

Despite their global jihadist rhetoric, these groups are the product of local contexts and specific political, economic and social factors. They opportunistically use international jihadist slogans to bolster their legitimacy in areas where the population has become mistrustful of the authorities. Often, they try to control cross-border trade, as they tend to operate in small, mobile groups around the border areas with neighbouring countries (see AFRICA: Opportunism and localism drive militants - January 14, 2015).

Although unlikely in Algeria -- where the state and the army retain a strong presence -- jihadi groups may try to take advantage of rising tensions and radicalisation in Ghardaia to gain local support and recruits. This would represent a strategic asset for such groups.

Locals can help identify high-value targets and provide assistance during operations. For example, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a native of Ghardaia who conducted the attack against the Tiguentourine gas complex in January 2013, knew the area well, and there were suggestions that he had help from local guards.

Regional environment

Algeria has been beefing up its borders and sending more troops to monitor its frontiers with Libya, Mali and Niger. The country has closed all its land borders (except the one with Tunisia), and military zones have been set up that are accessible only with special security clearance.

However, policing these borders is a difficult task given the challenging terrain and long borders (Tunisia -- 965 km, Libya -- 982 km, Niger -- 956 km, and Mali -- 1,376 km).

In addition, neighbouring countries are unable to patrol their side of the borders effectively. Most significantly, Libya's instability is providing shelter, weapons and smuggling profits to extremist and other illicit groups, including people-smugglers.

Government strategy

The government has tried to mitigate external threats through combining the increased border deployment with diplomacy. Algiers has hosted several peace negotiations both for Mali and Libya.

Internally, the government has struggled to provide a sustainable solution to grievances in the M'zab valley. It had previously relied on local elders as intermediaries and peacebrokers to resolve conflict, but has since failed to realise that this strategy no longer works: the new generations are just as mistrustful of these elders as they are of local government representatives.

Furthermore, the strategy of containing outbreaks of violence by deploying police and promising development and redistribution of housing and land is also under pressure. Algiers has routinely failed to deliver on these promises, breeding mistrust and feeding perceptions that the central government is corrupt and incompetent.

Trust in the government is likely to be further eroded with the fall of government revenues as a result of the halving of oil prices since mid-2014. Having failed to improve socio-economic conditions nationwide during the period of high oil prices, Algiers' capacity to buy stability will become increasingly limited as revenues shrink. The army can keep a lid on violence in Ghardaia for now, but clashes could escalate again once the army is removed (see ALGERIA: Finances weaken capacity to buy stability - February 6, 2015).

Ghardaia is symptomatic of government failure to meet the population's needs

Outlook

Events in Ghardaia have been exacerbated by the local context -- mainly longstanding animosity between Mozabites and Arabs -- but at the root is the government's failure to translate financial wealth into inclusive growth.