RCEP will step into gap as Trump pulls out of TPP

Trump has sunk the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, creating space for one that includes China

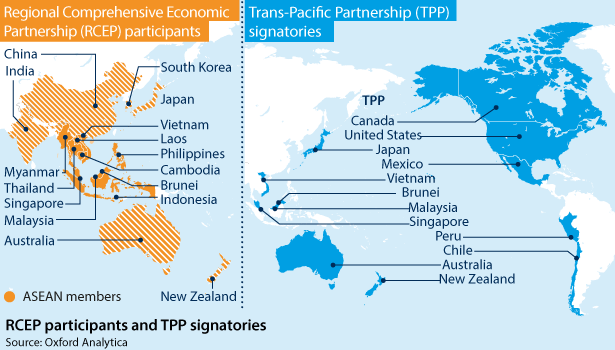

Shortly after Donald Trump was sworn in as US president on January 20, his administration announced withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. This leaves the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which unlike TPP includes China, as Asia's most ambitious planned regional trade agreement. The RCEP encompasses North-east Asia, South-east Asia, India, Australia and New Zealand. It has so far received less attention than the larger, more comprehensive TPP, but is now more likely to happen.

What next

The political will necessary to conclude the RCEP exists in all the participating countries, which are not undergoing the 'anti-globalisation' wave currently sweeping North America and Europe. It may be still difficult to meet the 2017 target for reaching the accord, but the possibility of concluding it within two or three years is high.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The TPP's collapse leaves China as the leader of large-scale regional economic integration, with the RCEP as the main pillar.

- The RCEP will probably be more open to new members than the TPP would have been.

- The RCEP may enhance the regional and global role of China, potentially contributing to bilateral rivalry with the United States.

Analysis

The RCEP involves:

- China, Japan and South Korea in North-east Asia;

- the ten ASEAN members in South-east Asia; and

- three non-East Asian countries -- India, Australia and New Zealand.

These economies account for about half of the world's population, and about 30% of the global GDP.

Washington withdraws

The United States played a key role in negotiations on the TPP, which targeted:

- exceptionally high levels of trade and investment liberalisation;

- high standards for protection of intellectual property rights; and

- tough limits on government regulation and state-owned enterprises.

However, now that Trump has withdrawn the United States from the TPP, the agreement will have to be renegotiated by the other participants and will be long-delayed and perhaps abandoned. That leaves the RCEP as the most significant integration platform for the whole of the Asia-Pacific, including most of the countries that were involved in the TPP.

Taking the TPP's place

Although the RCEP is expected to cover a range of areas and issues almost as wide as the TPP, the degree of liberalisation will be significantly lower and the number of exceptions and permitted safeguards greater.

Liberalisation will be lower than under the TPP

The number of participants may increase, especially if the TPP remains stalled. For example, Beijing foresees membership of South American countries such as Chile and Peru (see LATIN AMERICA/CHINA: Trade agenda sees new phase - November 25, 2016). Beijing emphasises its intention to keep the scheme open to any prospective members.

Long negotiations

Negotiations on the scheme were launched at the end of 2012 in Cambodia.

The number of participants in the RCEP talks is larger than the TPP -- 16 versus twelve. Also, they are more diverse. Unlike the TPP, it includes the two most populous countries -- China and India -- which have very different industrial structures:

- China is the world's largest exporter of goods and the largest net importer of services.

- India is a major exporter of services and net importer of goods.

Unlike the TPP, RCEP also includes the poorest (though fast-growing) countries of South-east Asia: Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar (see SOUTH-EAST ASIA/US: Ties will be mixed under Trump - December 29, 2016).

All this complicates balancing the interests of participants. Proposed solutions often differ from the TPP approach.

The initial December 2016 deadline for reaching an accord was missed after 16 rounds of negotiations and six ministerial meetings. The participants now seek to reach an agreement by the end of this year. The 17th round of talks is to be held in February-March in Kobe, Japan.

The solutions proposed for managing divergent interests differ from those of the TPP

Two chapters of the final agreement have been completed: on economic and technical cooperation; and on small and medium-sized enterprises.

Coverage

China emphasises its intention to make the RCEP the basis for trade rules in the Asia-Pacific region, while Japan is keen to provide a high level of liberalisation comparable to that of the TPP.

The 16 prospective members are discussing:

- trade in goods;

- trade in services;

- investment;

- rules of origin;

- intellectual property rights;

- competition; and

- e-commerce.

Unlike the TPP, they do not cover:

- labour;

- the environment; or

- state-owned enterprises.

The participants have agreed to discuss goods, services and investment as one package, primarily at India's insistence. Delhi was concerned that liberalisation of trade in goods would be given priority over services trade and foreign investment.

India has a competitive edge in services, and large Indian companies are becoming important foreign investors in the region. China, Australia and some other participants initially intended to discuss those issues separately. Beijing attaches priority to liberalisation of trade in manufacturing, particularly light industrial goods.

Tasks

Negotiators are now working to finalise the maximum number of goods for which import tariffs will be either eliminated or significantly reduced. They have agreed on a single-tier system of tariff reduction for all participating countries, while initially a three-tier system had been envisaged. However, reaching an agreement on tariffs for particular products is not easy.

India and some other countries fear a massive inflow of Chinese products once import tariffs are eliminated or reduced. Until recently, many Asian countries enjoyed surpluses in their trade with China due to a rapid expansion of the Chinese market and their exports of parts and materials used in the manufacturing of the made-in-China products exported to North America and Europe.

They are now running deficits. Exports to China are growing more slowly because the growth of the Chinese market is slowing and because Chinese domestic producers of parts and materials are increasingly competitive with imports.

To address the trade imbalance problem, India may require longer deviation periods for reduction or elimination of duties on goods imported from the countries with which it has large trade deficits. It may also offer to introduce a system allowing different tariff concessions for different RCEP member countries.

Liberalisation of trade in services is also a thorny issue. One challenge is finalising a Mutual Recognition Agreement, meaning recognition of the professional regulatory bodies of one country by another, for instance in engineering, architecture and accountancy.

Participants' views also differ on the protection of intellectual property rights, especially for pharmaceuticals. Tokyo and Seoul want higher standards, close to those of the TPP, while developing countries, concerned about access to medicines for low-income households, push for looser rules.

Good prospects

Compromises leading to agreement on the issues above are feasible.

ASEAN collectively has already concluded free trade agreements (FTAs) with the other six participants, and all 16 governments have accumulated experience of reaching agreements on the complicated issues that 'mega-FTAs' confront.

_350.jpg)