Policy will be key to supporting cashless consumption

‘Cashless’ payments are growing fast, but policy will be key to ensure inclusion, security, privacy and competition

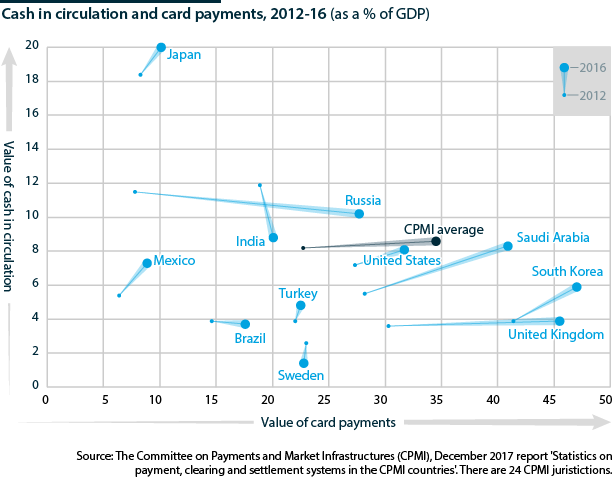

Transacting electronically is quicker and cheaper than using cash, provided the infrastructure is in place to support the transactions. Across the world, the number of electronic transactions and the supporting infrastructure has surged over the last two decades. Card payments averaged 25.3% of GDP in 2016 in the 24 countries the Committee for Payments and Markets Infrastructure covers, up from 12.8% in 2000. Despite this, cash retains a key role, paradoxically even more since the global financial crisis, as ultra-low interest rates in the ten post-crisis years reduced the opportunity cost of holding cash.

What next

China and other low and middle-income countries will lead the growth of cashless payments but will monitor the policies advanced countries adopt to ensure as much of the population as possible can participate and benefit from a cashless society. More regulation is likely, especially to address privacy and security, while schemes to assist vulnerable members of society directly will proliferate. Cash will decline as a means of payment but will retain its role as a store of value.

Subsidiary Impacts

- All cashless transactions are automatically tracked, forcing consumers to sacrifice more privacy without the ability to ‘opt-out’.

- An individual’s credit standing will gain importance and may become as key to gaining employment as it is to accessing financial services.

- There will be a digital divide not only in access to and exclusion from financial services but also the ability to pay.

- Payments for services could become the fastest-growing category of cashless transactions.

Analysis

Non-cash transactions grew by 11.2% to reach 433.1 billion dollars in 2015, the highest growth in a decade, and the latest World Payment Report estimates that volumes of non-cash transactions will grow by more than 10% between 2015 and 2020. Non-cash transactions in emerging markets are expected to grow by closer to 20% over this period, and by around 5% in advanced markets.

For the individual, the ubiquity and seamlessness of cashless payments depends on the robustness of the digital infrastructure and the network of merchants equipped to accept cashless payments. Point of sale (PoS) terminals have fallen in price over the last fifteen years, enabling more businesses to acquire them and they have proliferated across advanced and emerging markets (see PROSPECTS 2017-22: Fintech - December 5, 2016).

In the United Kingdom, United States, Japan, Australia, euro-area and Sweden, card payments as a share of GDP doubled or more between 2000 and 2016. In China, India, Brazil and Russia, card payments trebled or more as a share of GDP over the same period.

The most advanced cashless adoption markets share common traits:

- Non-financial domestic actors, often technology or internet firms are driving cashless growth.

- The government is overtly supportive, or not interfering.

- Cultural and consumer behaviours are amenable to cashless payments.

China and India are leading cashless adoption among emerging markets, accounting for 32.1% of non-cash transactions in 2014-15, and growing by more than 20%, treble the 6.8% mature markets growth.

1/3

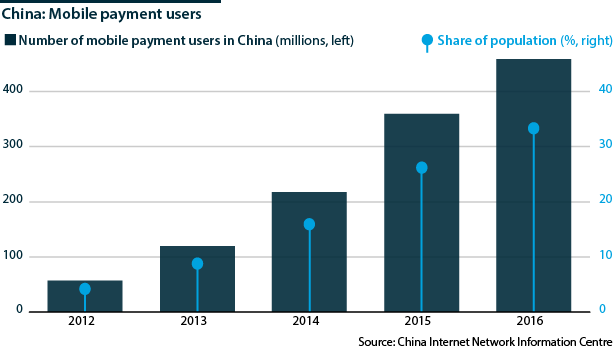

- Share of China's population that made mobile payments in 2016

China

In China the technology and internet companies Alibaba and Tencent have driven the growth. Alibaba's Alipay and Tencent's WeChat process over 90% of the country's mobile payments. The Global and China Mobile Payment Industry Report for 2017-21 estimates that mobile payment transactions reached 294.97 trillion renminbi (46.4 trillion dollars) in 2017, a 41.4% increase from 2016, and expects transactions to reach 793 trillion in 2021.

For Alibaba and Tencent Mobile, while the fee revenue is substantial, typically 0.6% of transactions, the consumer data they can gather is transforming their relationships along the supply chain from buyers to clients, enabling them to customise their product and service offerings. However, regulation will increasingly address the security and privacy risks this raises.

India

Aadhaar is a biometric database that uses a twelve-digit digital identifier authenticated by finger prints and retina scans. Before its launch in 2009, half of Indians had no form of identification. By 2016, 1.1 billion, or 95% of the population, had proof of identity, giving them access to public and financial services and helping to reduce fraud and corruption. Since Aadhaar's launch, 270 million bank accounts have been opened.

The 2016 rollout of India Stack enhanced the digitalisation infrastructure, allowing people to store and share personal data through a series of secured and connected systems in the Aadhaar framework.

In November 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government removed India's two most common banknotes, the 500 (7.5 US dollar) and 1,000 rupee notes from legal tender (see INDIA: Demonetisation will dampen 2017 GDP growth - November 23, 2016). Demonetisation disproportionately affected the poor, choking off working capital for cash-reliant businesses and the rural economy, which largely lacked the infrastructure for processing cashless payments.

However, the policy enjoyed some success. In August 2017, Modi estimated that 5.7 million more people paid tax after the demonetisation.

Private sector efforts are also gaining traction. Digital transactions and mobile wallet subscriptions are seeing significant growth. The Alibaba-backed Paytm platform has 250 million subscribers, double from 2016.

Global developments

In mature markets, the debate is focusing on privacy, fairness and inclusion.

Inclusion risk

The difficulty of achieving 'cashless inclusion' is disproportionately higher for the poor, near-poor or undocumented. Cashless inclusion largely requires financial inclusion, creating difficulties for the unbanked and undocumented. M-PESA in Kenya does not require users of its mobile payment platform to have a bank account but for most platforms, mobile payments are tied to bank accounts.

In Sweden, cash in circulation accounts for less than 2% of GDP, compared to more than 8% in the United States, Japan, the euro-area, China and India. The law allows shops to refuse to take cash.

Sweden is leading the way not only towards a completely cashless society but also towards everyone being included

The magazine Situation Stockholm has equipped its homeless sellers with credit card readers, highlighting the role that direct assistance will play in ensuring vulnerable populations are included in cashless societies. Indeed, Sweden's central bank governor urges that the cashless transition occurs "at a rate that does not create problems for certain ...groups or exclude anyone".

Oligopoly risk

The Bank also highlighted that in Sweden a small number of banks and non-bank institutions are responsible for all payments, and that widening this would make the economy more resilient to a crisis. However, in many sections of the supply chain, there is scope for start-up firms to build market share. Improving the regulation and infrastructure around cashless payments will support and encourage competition and innovation.

Debt risk

The advent of payment platforms morphing into consumer financial services platforms runs the risk of making it easier to acquire debt, potentially changing attitudes in countries that have traditionally avoided accumulating consumer debt.

In China, short-term loans to households rose by 13% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2018, the most since 2016. However, the government has put in place measures to curb this, tightening access to payment licenses and reducing the number of non-bank payment institutions to 247.

Starting this year, all electronic payments will go through a central bank payment clearing platform, Wanglian. Last month the central bank also implemented rules on mobile payments made by QR code (machine-readable code containing price and product information). Daily transaction limits will be set at three levels for users based on their demand and risk profile; at 500 renminbi, 1,000 renminbi and 5,000 renminbi.

_350.jpg)