Facebook seeks new users and markets as troubles mount

Facebook's multiple political, reputational and economic challenges reflect tensions with its underlying business model

Updated: Jan 30, 2019

Facebook's reputational decline has yet to bottom out · All Updates

Facebook’s financial performance is determined by its success in adding, retaining and engaging active users of its products, particularly its eponymous social media platform and photo- and video-sharing service Instagram. Its North American and West European markets are reaching their ceiling for new users while removing fake accounts, estimated by the company to account for 3-4% of the total, is reducing overall numbers. Meanwhile, privacy, data sharing and security, and false and bot-created content concerns, put user engagement and retention at risk, further endangering revenue.

What next

Facebook’s response to criticism in the United States and Europe about abuses of its services will be constrained by the imperatives of its business model. As a result, Facebook will aggressively seek its next 1 billion users in developing economies, particularly in South-east Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where regulatory concerns will be minimal. The spectacular growth rates of its revenue and profits may slow, until it raises advertising yields in its new markets to the levels it extracts in its mature ones.

Subsidiary Impacts

- A global regulatory regime against social media is highly improbable.

- Some US and EU regulation could be useful for Facebook as barriers to entry, as it does in such industries as banking and airlines.

- Sustaining advertiser loyalty is as vital to the sustainability of Facebook’s business model as growing users.

Analysis

Facebook is an advertising business based on a technology platform. Adverts generate nearly all its revenue (24.8 billion dollars out of total revenue of 25.2 billion in the six months to June 30), using a traditional model -- aggregating a qualified audience and selling marketers access to it.

Payments services and fees are the company's other revenue stream (364 million dollars for the same six months).

Business lines

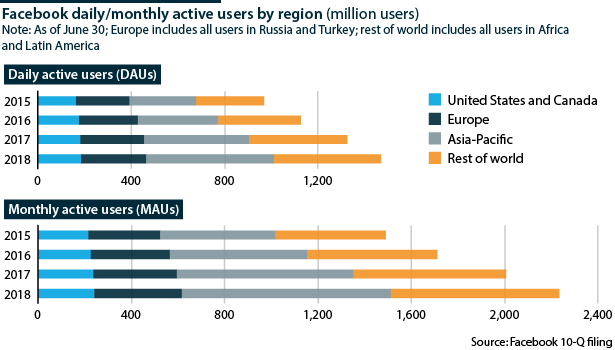

Facebook's primary business line is its social media platform, for which it claims 1.47 billion daily active users (DAUs) and 2.23 billion monthly active users (MAUs). It also owns Instagram, the WhatsApp messaging application and Messenger, its instant messaging (IM) service for mobile.

Instagram and WhatsApp are among more than 60 companies acquired by Facebook during its history, at a cost of 23 billion dollars. Like other technology giants, it buys companies to acquire technology, products, specialist talent, audience and potential competitors.

Advertising model

Facebook differs from traditional publishers in several key aspects, including:

- its ability to micro-target advertising based on the data it collects on its users;

- its auctioning of ad inventory to marketers;

- not creating content but providing a free platform on which virtually anyone can publish theirs; and

- filtering content, so that users are served content they are most likely to share.

This has let it build an audience at unprecedented scale and speed for a firm started in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg, its chairman, chief executive and controlling shareholder (60% of the voting stock).

It generates revenue each time it displays an advertisement on one of its services or on those of third-party affiliates (an 'ad impression'), or when a user performs an action such as clicking on advertisement (including political messaging) to be redirected to the advertiser's content. Using the data it has accumulated on its users, Facebook can target advertisements against qualified audiences and relevant content, and sells advertisers the capacity to reach narrowly defined receptive audiences, in groups as small as 20.

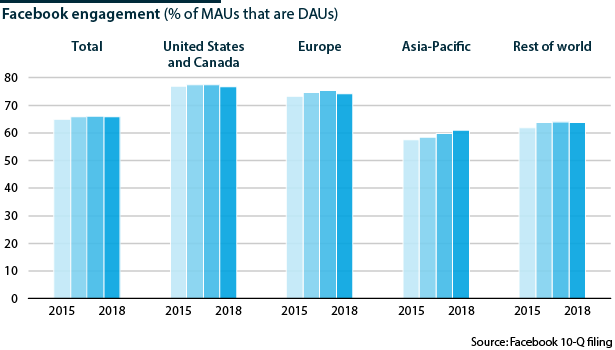

Thus scale is critical to Facebook's business model, not just in generating revenue volumes but making each message more valuable by being more effectively targeted. The more users Facebook has, and the more times they look at their feed, the more ad inventory is created and the more data the company acquires on its users.

Facebook's ability to get its users to share more and more content has been critical to the working of (for Facebook) this virtuous circle.

Social media tend to favour positive sentiment over negative and exaggeration over subtlety. This causes 'echo chambers' and reinforces existing opinions to the exclusion of contesting ones.

Facebook's motivation to drive scale through content-sharing has made it, until recent scandals, necessarily blind to the provenance of its content, whether human- or machine-created. This has provided an immense opportunity for malevolent actors.

Critical juncture

Facebook faces several scandals, particularly the Cambridge Analytica data-sharing abuses and its alleged use by Russian meddlers in the 2016 US presidential election (see RUSSIA: US charges designed to prove hacking - July 27, 2018). These reflect problems with its business model.

Maturing markets

North America and Europe are Facebook's largest markets, but are approaching saturation. Growth in the number of MAUs has slowed to a crawl. In the United States and Canada in the fourth quarter of 2017, Facebook saw a slight quarter-on-quarter decline in its DAUs.

Also, users are spending less time on the platform, and starting to become older (a less valuable audience to advertisers). Among younger users, Facebook has strong competitors such as the photo-messaging service SnapChat.

Abandonment risk

Failure to add new users and loss of or lower levels of engagement by existing users, because they are opting for new or rival platforms, or cutting back their usage and sharing because of privacy or data abuse concerns, is a direct threat to Facebook's business model. Facebook does not have a single user tied to a long-term contract (and barely any advertisers, either).

Facebook could also lose the support of third-party developers that it relies on to integrate Facebook's products and services with their own and are thus a critical distribution channel through which Facebook grows users and usage.

This a particular risk in mobile, which the campany says generates a "substantial majority" of Facebook's advertising revenue. Facebook is reliant on carriers, operating systems, products such as browsers and standards over which it has no direct control to monetise the numbers and engagement of users; or users could lose trust in third-party apps as a result of their data practices.

Regulatory exemptions

US regulation treats Facebook more like a telephone company than a publisher

Facebook has benefited in the United States from internet companies' exemption under Section 230 of Title V of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This immunises it from responsibility for the content on its platform provided by third parties, giving it a legal status more like a telephone company than a publisher.

It has also been exempted from the 'sunshine' provisions of political advertising imposed on broadcasters. Malevolent actors have taken advantage of this.

Changing political winds

The public mood in the United States and Europe favours some regulation.

However, banning political advertising is difficult to enforce. Definitions would become blurry quickly and, in the United States, run into First Amendment challenges. Greater transparency regarding the provenance of political advertisements on television, as is already required in the United States, is possible but its effectiveness is untested.

Banning all targeted advertising would be unfeasible. It would undercut Facebook's business model and thus be fiercely resisted. 'Big Tech', including Facebook, 'owns' a large chunk of the political spectrum, starting with the Democratic Party, reflected in the latest tweets by US President Donald Trump about social media platforms silencing conservative voices.

There is also a question whether enforcing it is technically within the competence of regulators, especially if Facebook has further diversified its product line by the time any legislation is enacted.

Anti-trust regulations

Anti-trust action to enforce a break-up of component services (Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger) could be achieved but would take time (see EU/US: 'Big tech' faces tighter competition oversight - August 28, 2018).

European regulators, with no domestic large technology companies to defend, might choose to be bolder. Germany is the standard bearer but is advancing slowly and cautiously.

Facebook has already had to adapt products and services to comply with the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and similar changes made in the United States and other markets to protect personal information online by seeking consent to use personal data.

The EU could also seek to constrain Facebook and other tech companies by using taxation, such as the proposed levy on the revenue of the global technology companies. Both fronts will meet stiff resistance.

During the Trump administration, either approach would probably be matched by retaliatory US tariffs, and tirades against yet another EU 'anti-US' business practice.

Facebook reportedly lost some 1 million European MAUs after GDPR, and it said some users' desire to avoid targeted advertisements may lead to a modest revenue hit, as it will reduce marketers' ability to target their ads effectively.

This could manifest itself as low ad rates, low ad volumes or both.

Privacy, 'fake news' and bot-generated content

Advertisers want to pitch products to humans not bots

Concerns about these three factors and the power of technology firms is raising the possibility of the regulation of social media companies, not only in the United States and EU but also in larger emerging economies such as India (see INDIA: Social media face opposite pressures - August 31, 2018).

In addition, legitimate advertisers are concerned about the scale of bot-driven traffic on Facebook (see INTERNATIONAL: Distortion by social media bots to rise - July 25, 2018). They want to reach humans who buy goods and services, not bots that do not.

They also have reputational concerns, such as a wish not to be associated with objectionable content published on Facebook products by third parties, discomfort with Facebook's user data practices and uncertainty regarding their own legal and compliance obligations in what are likely to be regulatory regimes in flux.

Censorship and content moderation

Outright censorship spreads beyond China, Iran and North Korea. Other countries already restrict access to Facebook products from time to time for varying periods, when they consider Facebook has violated local laws or threatens civic norms.

Facebook also struggles with internal policing of its content. It is expending considerable resources on moderating material that may violate its 'Community Standards', in large part to protect its brand and mitigate potential liability.

Much of this is done using artificial intelligence (AI), which is generally successful at identifying spam and nudity that should be removed, but has so far proved ineffective with hate speech (it reportedly fails to identify more than three-fifths of the hate speech posted on Facebook).

AI struggles with the nuances of human languages (Facebook operates in more than 100) and with cultural context. Zuckerberg's notions of a global Facebook community with shared values that can be codified into a standard set of rules for AI moderation is a fiction of techno-utopianism that does not fit the realities of a world of multiple religions, cultures and languages, and may be fundamentally irreconcilable.

Facebook tacitly recognises this by having culture- and country-specific moderation guidelines, often where its business model would be at risk did it not. Civil society groups anyway have concerns about the arbitration of free speech by a private company.

Legal challenges

Facebook faces multiple class action and derivative lawsuits as a result of data abuse by a third-party developer (unnamed but clearly Cambridge Analytica). Regardless of their outcome, these cases will cost substantial management time and legal fees.

Similarly, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development has filed complaints against the company, accusing it of helping landlords and home sellers violate the Fair Housing Act by offering advertisement targeting that excludes certain demographics related to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and religion. Facebook has said it is removing more than 5,000 categories of ad targeting.

Social media companies may also be vulnerable in the United States to activist lawsuits claiming consumer fraud, especially if there is coordinated conservative action against being 'muzzled' by 'liberal' technology company chief executives.

New business models

Potential new business lines for Facebook could offer more premium content (including professional sport streaming or, in the longer term, augmented and virtual reality) to attract new users or more frequent usage of existing services.

It could process digital payments. China's most popular social network platform, Tencent's WeChat, embraces messaging, games, online shopping and financial services. WeChat users can get almost everything they need from their smartphone without leaving the WeChat app.

The firm may focus on attracting more advertisers and getting the 6 million Facebook already has to spend more by using more of the company's outlets. One example of this is its efforts to get businesses to use more Facebook mobile services.

It could pay users to surrender their data. Issues around trust would make it difficult for a social media company to operate such an exchange. It might be a role for government, or for a blockchain implementation.

All these options are costly, requiring development investment that would erode profit margins. Facebook has said its expenses are growing faster than its revenues and this is likely to continue at least into 2019.

Emerging markets

Facebook's future is in emerging markets. Its expects its jump from 2 billion MAUs to 3 billion will come predominantly from there, particularly South-east Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Facebook's audience growth is already increasingly coming from those regions, where it already has more than 1 billion users. Over the last two years, for each user added in North America or Europe, Facebook added six in the Asia-Pacific region and four in the rest of the world (primarily Sub-Saharan Africa).

Demographics and rapidly increasing rates of internet connection in emerging markets suggest the gap will continue to widen.

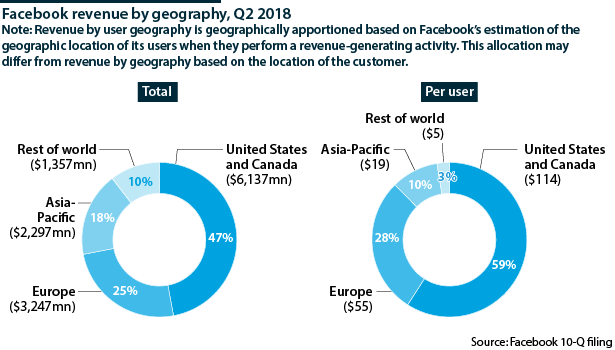

Yet financial returns will lag. The rate charged to the advertiser is a third variable in Facebook's revenue generation, and thus the size and maturity of the online advertising market in a given region is a key determinant of local ad rates as is the scale of the data Facebook has on its users there. The average revenue generated per Facebook user in the second quarter of 2018 in the United States and Canada was more than nine times higher than in the Asia-Pacific region.

In addition, Facebook has to invest in infrastructure such as broadband distribution by satellites or large drones to reach and serve these scattered and under-connected markets.

Facebook may follow Google and Apple's lead into China

China is the major blank spot on the map for Facebook, but developing products consistent with Chinese censorships would expose the firm to reputational risk in other markets; however, Apple and Google provide precedents.

Outlook

By contrast with Western countries, these regions are likely to remain regulation-free for quite a while. Facebook will have an opportunity to lock up these markets, including with other revenue lines where it has no more than a toehold in developed economies, notably payments services, which are mobile-phone-centric in developing countries.