‘Nationalism-lite’ will contaminate mainstream Europe

Mainstream, not extremist, parties will be responsible for the surge in nationalist politics

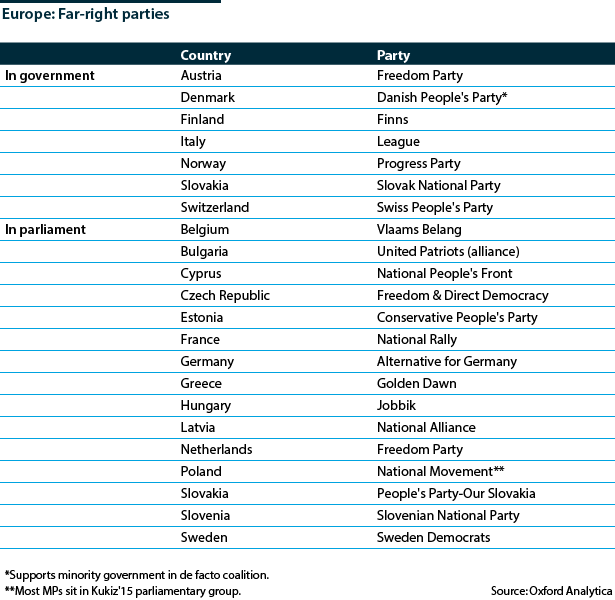

In contemporary Europe, far-right parties and extremist voices lack the electoral support to reach the levers of power without mainstream parties’ support. Such parties’ willingness to ally with extremists in government in Austria, Finland, Bulgaria, Denmark and Switzerland, or reluctance to move swiftly to curb nationalist voices in their midst in the United Kingdom, Romania, Poland, Croatia and Hungary, are the main reasons behind the prominent nationalist agenda in Europe and elsewhere.

What next

Support for extreme nationalists will increase but hit an inevitable firewall. Their access to power is limited by the extent of mainstream parties’ willingness to include them in cabinets as parties or as individuals. Yet despite this important ‘gatekeeper’ role, established parties will be tempted to incorporate nationalist rhetoric or to ally with extremists.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The increasing inclusion of far-right parties in cabinets will further legitimise societies’ retreat from the values of liberal democracy.

- Mainstream parties will increasingly feel compelled to make concessions to nationalist electoral preferences.

- Democratic institutions will continue to weaken in Central-Eastern Europe.

- EU parties will face mounting challenges in constraining centrifugal forces.

Analysis

Mainstream parties' affinity for extremists on their side of the political spectrum is providing an early warning of a weakening in liberal democracy.

Accepting or pushing back

There are 22 far-right/nationalist parties in European parliaments. The only EU countries without extremist parties in the national parliament are the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Lithuania, Croatia, Ireland and Romania.

In some countries, their size and influence are marginal: Estonia's Conservative People's Party or Belgium's Vlaams Belang. In others, they have negotiated their way into government as coalition partners: in Austria, Finland, Italy, Bulgaria, Norway and Slovakia.

Denmark has had minority governments supported by the far-right Danish People's Party. Sweden has seen similar negotiations with the Sweden Democrats after the 2018 elections.

Mainstream parties have a gatekeeper role for democracy and their approach to extremists can predetermine outcomes. When they accept alliances with or endorsement of the actions of far-right movements or candidates, they open the gate.

Mainstream parties may allow the far-right political access

On the surface, once these parties are included in the state machinery, there is a constraining effect on their behaviour centrally. The nationalist parties in the Bulgarian, Austrian and Finnish cabinets, for example, have slightly moderated their more abrasive stances.

However, when their members express an aversion to the values of liberal democracy, they do it from the elevated platform of a government position. This sends signals to members of society that their own aggressive nationalist attitudes need not be constrained, but may be expressed as legitimate attitudes in public. Consequently, restraint as a social norm is replaced by polarising passions, and nationalism increases.

The consequences of increased nationalism will be seen in the upcoming European Parliament (EP) elections (see EUROPE: Right-wing populism will change politics - September 20, 2018).

In other cases, mainstream parties have pushed back and collaborated across the ideological spectrum to keep Marine Le Pen from the French presidency and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) out of government. Similarly, the Freedom Party (FPOe) candidate lost the 2017 election to the Austrian presidency to the Greens' Alexander Van der Bellen, who had cross-party support from mainstream parties.

This came at great electoral cost for centre-right and socialist mainstream parties in France, Germany and Austria. As a result, Austria's centre-right was the first to stop isolating the FPOe, Germany's Social Democrats and Christian Democrats are struggling to retain support and France's mainstream parties have all but disappeared, leaving the centre open to newcomer En Marche.

Electoral pressures will continue to mount, leading centrist parties to incorporate populist-nationalist rhetoric. A recent example is the change of rhetoric and policy by French President Emmanuel Macron to conciliate the 'yellow vest' movement (see FRANCE: Protests will limit Macron's electoral appeal - December 3, 2018).

Nationalist agendas will increasingly drive party politics and government decisions

Incorporating nationalist ideology

In such Central-East European (CEE) countries as Croatia, Bulgaria, Hungary and Poland, mainstream parties employ nationalist rhetoric themselves and nurture voices within their midst that are allowed to 'do the dirty work' for the party's populist ends. This has ensured the electoral success of the Croatian Democratic Union, Citizens for Bulgaria's European Development, Hungary's Fidesz and the Polish Law and Justice (PiS), and encroached on competing far-right movements in these countries.

Romania also has a social-conservative government led by the Social Democrats (PSD), whose use of nationalist discourse was instrumental in winning the 2016 elections. Their need to consolidate a large voter base may prompt a move further to the right.

Nationalist campaigning is often a vote-winner

On November 12, the march celebrating 100 years of Polish independence saw far-right movements and the governing PiS negotiating for a peaceful joint demonstration of Polish patriotism. However, the open display of anti-Semitic and Christian white supremacist symbols alongside PiS and President Andrzej Duda was worrying.

The conservative PiS was already under scrutiny for its authoritarian tendencies; it has now been associated with fascist-style groups behaving aggressively and chanting slogans against anything they perceive as threatening Polish 'white pride'.

PiS's stated intention was to overwhelm the far-right protesters. However, this is an example of gatekeepers leaving the door open in a political system that is already doubtful when it comes to upholding civil rights.

European parties' loosening constraints

European party groups have their own gatekeeping role that will be tested after the 2019 EP elections. A surge of Euro-sceptic parliamentarians is to be expected.

EPP

The European People's Party (EPP) will once again have to deal with Hungarian, Bulgarian and Croatian members, who will be on the group's right wing and will most likely have come first in the preferences of their national constituencies.

Croatia and Bulgaria will continue to escape scrutiny, but Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban's authoritarianism cannot be ignored. However, it is unlikely that the EPP will want to part ways with Orban (see HUNGARY: Isolation in EU will not harm Orban at home - October 12, 2018).

ALDE

The EU's liberal Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) faces similar dilemmas in the case of the Romanian junior coalition party also called ALDE, and the Euro-sceptic Czech ANO 2011. So far, Guy Verhofstadt has openly dissociated his group from Romanian ALDE's attacks on the rule of law.

PES

The Party of European Socialists (PES) will be severely hit by the defection of traditional supporters to far-right and challenger parties throughout Europe. Consequently, the hold over their electorates will loosen of the few remaining successful social-democratic parties in Europe.

In the past, PES suspended the membership of Slovakia's Direction-Social Democracy for forming a coalition with the far-right Slovak National Party (SNP), but this was later reconsidered. The SNP is again a member of the Pellegrini cabinet.

Similarly, Romania's PSD will win the EP elections and deliver a by no means negligible ten members to PES. This consideration makes the PES leadership wary of visibly condemning the PSD's attacks on the rule of law.

Outlook

The model of France and Germany, where parties worked across political ideologies to keep Le Pen's National Front and AfD, respectively, out of the presidency and government, will come under increasing pressure.

For both mainstream national and European parties, the gatekeeper role which has long-term benefits for democratic governance is being subverted by the lure of the instant gratification of more votes. This will sustain the spread of nationalistic attitudes throughout Europe in response to cultural insecurities and economic malaise.