Russian-US arms treaties erode in new era of mistrust

Decades of commitment to curbing nuclear arms are coming to an end, with no vision of an alternative to competition

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said on March 5 that Moscow would deploy intermediate-range missiles in any region where the United States did so, but would avoid being drawn into an arms race. The likely end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty will be an important marker in the decline of international stability and a particular blow to long-held assumptions about European security. It comes at a time when US-Russian dialogue has stalled and uncertainties about intentions and evolving technologies abound.

What next

After INF, the remaining treaty covering long-range nuclear weapons will be in jeopardy as consensus about the intrinsic value of arms control is eroded. China will stay aloof from the discussion, at least until it feels threatened by new US and Russian deployments.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The INF issue will feed Moscow's narrative about encirclement by hostile forces.

- Despite delays to arms programmes, Russia has proved adept at developing and adapting smaller missile types.

- President Donald Trump is unlikely to engage meaningfully with Russia on the detail of arms control.

Analysis

The 1987 Treaty on Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) was a landmark agreement that eliminated an entire category of nuclear-capable delivery systems: land-based ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometres.

By agreeing to strip these systems from their arsenals, the United States and Soviet Union resolved the emerging "Euromissile crisis" and removed the risk of rapid escalation posed by nuclear-capable missiles based in Europe.

Mutual permission for verification of weapons destruction enhanced the rising confidence between the two adversarial states.

INF's real value is its embodiment of mutual commitment and trust

Subsequent technical developments reduced the actual restrictive utility of INF. Russia and the United States have airborne and sea-launched versions of intermediate-range cruise missiles that are banned on land. China, never included in INF arrangements, has emerged as a modern military power with a large stock of intermediate-range missiles. Russian and Chinese tactical (under 500-kilometre-range) and intermediate-range missiles are 'dual-capable' for nuclear and conventional payloads.

The power of INF, and the gap that will be left by its loss, is its enduring symbolism -- not least to West European states that were direct beneficiaries of the deal and have remained its staunchest advocates.

Collapsing consensus

In January, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the United States was withdrawing from the INF treaty because of a continuing pattern of Russian non-compliance, through the testing and deployment of a treaty-violating missile system. Under the treaty's terms, this started a six-month process expiring in July with formal termination.

The impending end of INF comes amid a range of issues that cause anger in Congress and frustrate attempts by Russian and US leaders to repair relations. These include Russian military actions against Ukraine and in Syria, and ongoing revelations of election-related hacking and manipulation.

In this context, the collapse of INF is not an exceptional moment.

President Donald Trump's administration publicly warned Russia of its plans to withdraw in October and offered it a last chance to return to compliance (see US/RUSSIA: INF treaty end will destabilise Europe - October 22, 2018).

Nor is it surprising that INF withdrawal became an administration priority after John Bolton was appointed National Security Advisor. In previous roles, Bolton made no secret of his disdain for INF, which he compares to the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty from which Washington withdrew in 2001 during his tenure in government.

Despite meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin and calling for better relations, President Donald Trump seems to view INF as unsustainable. Amid ongoing investigations into his administration's contacts with Moscow, and with veto-proof majorities in both parties calling for a harder line on Russia, INF withdrawal may buy him some breathing space (see RUSSIA/US: Rift too great for summits to bring detente - July 25, 2018).

US concerns are not a post-2016 phenomenon. President Barack Obama's administration reportedly confronted Moscow on violations as early as 2011, at the apex of a purported 'reset' in relations.

Strategic stability frays

If the INF treaty is terminated, broader assumptions underpinning US-Russian arms control will come into question: the idea that treaties reduce the danger of unintended escalation, provide a baseline for mutual trust and demonstrate great-power responsibility to other nuclear-armed states (and aspiring ones).

Bilateral mistrust

The last time US and Russian officials held a round of 'strategic stability talks' to discuss the wide range of issues that could potentially raise or lower the risk of direct conflict between nuclear superpowers was September 2017 -- before the tenures of the current US national security advisor, secretary of state and acting secretary of defence.

There is no apparent consensus to renew the dialogue from current US officials. The Kremlin says it will await US initiatives before re-engaging in arms talks.

Misperceptions

This lack of communication comes during a period of uncertainty on both sides about nuclear posture and intentions on both sides.

The two sides neither talk nor grasp one another's intentions

The 2018 US Nuclear Posture Review makes provision for new low-yield nuclear warheads for intercontinental weapons and upgrades to existing tactical nuclear munitions (carried on aircraft) (see UNITED STATES: Success of new nuclear arms not certain - February 6, 2018).

This is a response to Russian development of low-yield warheads for tactical missiles, which Washington sees as part of an implicit strategy of limited first use. Yet opinion is divided on whether this is strategy: Moscow may also fear total nuclear war and seek additional deterrents to prevent this.

Speaking in October, Putin said Russia would never use nuclear weapons for preventive strikes and would launch them only when it was certain its territory was being attacked with nuclear arms. Such an escalation would result in mutually assured destruction.

On the Russian side, there is concern that modern US anti-missile systems could underpin plans to decapitate its arsenal before it could be deployed. This thinking in part dictates Russian upgrades to strategic missiles, including now with hypersonic warheads, to ensure they penetrate US defences.

In response, Washington is preparing to replace its ageing strategic missiles (see UNITED STATES: Missile defence plans prove unrealistic - January 23, 2019).

Long-range arsenal

After INF, only one arms control agreement will remain in force: the 2011 New START treaty, which will lapse in 2021 unless extended by mutual agreement (see PROSPECTS 2019-23: Nuclear arms control - December 5, 2018).

There is no indication that Washington is inclined to seek an extension. Trump called New START "a bad deal" in an early discussion with Putin. Bolton's views will also count: he was highly critical of New START when it was signed.

If New START survives beyond 2021, that alone will not stem the gradual erosion of arms control measures -- with implications for both strategic stability and global nuclear non-proliferation.

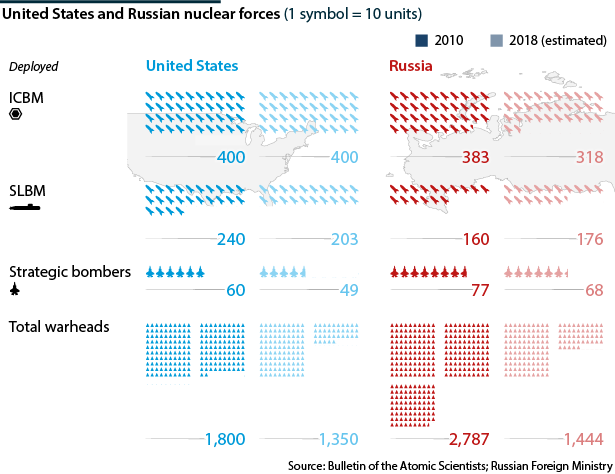

New START limits Moscow and Washington to 700 deployed strategic missiles or bombers and 1,550 deployed strategic warheads each. It says nothing about warheads in the tactical or intermediate ranges, about strategic warheads held in stockpile rather than deployed, about new hypersonic capabilities or about the emerging blurred lines between traditional nuclear deterrence doctrines and newer strategic capabilities such as cyber warfare, space-based systems and sophisticated missile defences (see US/RUSSIA: Nuclear arms treaty may lose relevance - April 24, 2017).

Non-proliferation

The present condition of US-Russia arms control worsens the prospects for global non-proliferation efforts as the 2020 review conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) approaches.

For half a century, the basic bargain of the NPT was a commitment by participating states not to pursue nuclear weapons in exchange for recognition of their right to peaceful nuclear technology and a promise by nuclear-armed states actively to pursue disarmament.

The UN General Assembly's resounding endorsement in 2017 of a universal Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons reflects the frustration felt by these states, since the other side of the bargain is manifestly not being kept.

Russia's next moves

The US announcement handed Russia a propaganda gift it was happy to exploit. Senior Russian officials accused Washington of "taking another step toward destroying the world" and promised a swift response.

Putin formally suspended Russia's INF participation on March 4.

If Russia genuinely intended to maintain the INF treaty, it could have invoked provisions for inspections written into the agreement. Bilateral expert groups would then have been empowered to examine controversial systems and confirm or deny violations.

No such mechanism was proposed or accepted, indicating that Moscow may have been as content as Washington to see its treaty obligations end.

Moscow has the advantage over Washington in ready-to-deploy weapons

Moscow flatly denies the US-claimed violations, even showing off what it said was the disputed 9M729 cruise missile to journalists (US officials rejected this as a sham), and levels counter-claims that US missile defence launchers, drones and dummy test missiles are in breach of the treaty.

Washington says the 9M729 (NATO designation SSC-8) has a range squarely within the INF-proscribed zone. It has apparently shared enough confirmatory intelligence with European NATO allies to win their agreement, although not necessarily their support for scrapping INF (see RUSSIA/US: INF treaty is at risk but not dead - November 23, 2017).

Assuming the 9M729 has been or will be deployed, Russia has the clear advantage, since US research into intermediate-class weapons is still in early stages.

While denying that the 9M729 is in breach of INF, Russian officials say the ship-launched, intermediate-range Kalibr cruise missile can be repurposed for ground launch by 2020.

Finally, Russia may recalibrate its intercontinental RS-26 Rubezh missile for intermediate range.

Intermediate-range systems would probably be deployed in Siberia, where mobile launchers enjoy survivability and concealment comparable to submarines. With such systems in place, Russia would gain additional deterrent power versus China and also Washington's allies in East Asia.

Although it has promised not to deploy intermediate-range missiles in the European theatre until and unless the United States does so, Moscow will be tempted to hint at that possibility. It has previously publicised deployments of Iskander short-range missiles in western Russia including forward-based Kaliningrad to send political signals.

European responses

Few US allies in Europe are eager to host a new class of destabilising nuclear weapons (see US/RUSSIA: INF treaty end will destabilise Europe - October 22, 2018).

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron have both decried the US withdrawal from INF and pledged to use diplomatic means to try to save the treaty.

Deep divisions between Washington and its traditional European allies were clearly on display during the February 2019 Munich Security Conference. The satisfaction of Russian and Chinese representatives at this state of affairs was evident, despite the lip-service paid to preserving arms control.

Cleavages within NATO complicate Washington's dialogue with its allies on the post-INF future.

Newer members such as Poland are eager to attract a maximum US troop presence on the ground, as concrete proof of US backing for NATO's Article 5 collective security guarantee. This might make these governments more favourably inclined toward hosting nuclear weapons.

Core US allies such as Germany, France and the Netherlands, have begun moves toward the creation of joint rapid-reaction forces. This is arguably a positive response to Washington's call for NATO partners to bear more of the security burden, but Trump has condemed talk of a 'European army' as an alternative to NATO.

US options east of Russia

Convincing US allies in East Asia to host intermediate-range missiles will be no easier than in Europe.

South Korea and Japan have enjoyed the security assurances provided by Washington's extended nuclear deterrence and significant troop presence in the region.

Both favour a diplomatic settlement with North Korea to enable a gradual normalisation of relations and would therefore be unlikely to welcome any US proposal to position a new class of nuclear weapons on their territories.

Chinese reluctance

The US decision to pull out of INF was partly justified by the argument that China was not included and should be brought into a future arrangement.

Unsurprisingly, Chinese officials take the position that the INF treaty was a bilateral agreement and that its demise, however regrettable, does not open the way for a binding trilateral arrangement.

Beijing never saw its nuclear arsenal as relevant to the Russian-US balance

With an arsenal that it claims is "tailored strictly to China's defensive needs", Beijing says it sees no reason to enter into the kind of formal arms control practiced by Washington and Moscow.

US officials say China's missile arsenal consists largely of land-based intermediate-range systems.

A range of 500-5,500 kilometres means China can target any potential adversary in East Asia and the Indo-Pacific region, using its vast territory to deploy highly survivable missile systems.

From a Chinese perspective, this posture is wholly defensive: if Beijing focuses on regional targeting, it avoids blundering into the delicate balance of US-Russian global strategic stability.

China's stance might change if, as some experts have suggested, both Washington and Moscow were to move toward new intermediate-range missile deployments in East Asia.

With no treaty constraints, Russia could quickly deploy road-mobile launchers armed with nuclear-capable missiles capable of hitting any target in China.

Washington might consider deployments on Pacific island bases or in any regional allies that can be persuaded to host them.

Either or both scenarios (Russian and US deployments) might remind Beijing why major powers have felt the need for arms control negotiations in the past.