Pandemic to deepen food insecurity beyond 2020

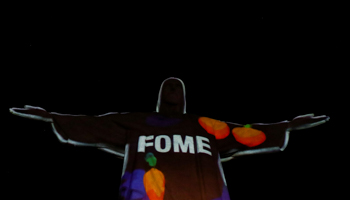

The World Food Programme has warned that the world is “on the brink of a hunger pandemic”

UN agencies have warned of increasing global hunger due to the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Some 135 million people faced ‘crisis’ levels of hunger in 2019, of which the majority were located in just two regions: 73 million in Africa and 43 million in the Middle East, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). The 2019 figure, already a four-year high, could nearly double to 265 million by end-2020.

What next

Global hunger will rise sharply this year, with vulnerable populations being pushed into crisis situations as remedial actions fall short. Recovery in 2021 will be tied to the pandemic’s knock-on negative impact on food production and food trade, which have not been experienced fully as yet, and would reduce supplies and raise prices.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Disruptions to agricultural input supply will negatively affect future planting seasons.

- Establishing national strategic food reserves will become more attractive, although these distort food markets.

- Automated food handling and fruit-picking will become more popular but technological challenges persist.

- Movement restrictions, especially at ports and transport hubs, will disrupt food trade throughout 2020 and possibly beyond.

Analysis

Food 'crisis' refers to Phase 3 of a five-tier scale used by governments, donors and aid agencies to classify countries' food security situations (Phase 4 is 'emergency' and Phase 5 'famine'). Phase 3 marks a livelihoods crisis, lack of food access and the need for external food assistance. The 265 million estimate for 2020 refers to people in Phase 3 or above.

Trade volatility

The pandemic is affecting both supply and demand in the food supply chain.

Supply-side

The World Trade Organisation has found that at least 17 food exporters have introduced some export restrictions on foodstuffs and agricultural products. Notably, Russia, the world's largest wheat exporter, has unusually set an export quota of 7 million tonnes for the April-June period (see RUSSIA: Moscow adjusts foreign trade to ensure food - April 3, 2020). Although this quota is in line with normal export volumes, the entirety of it has already been booked, creating uncertainty in the wheat market. Meanwhile, importing countries such as Egypt, the world's largest wheat importer, are building larger-than-normal stockpiles amid fears of continuing disruptions.

Most African countries are net food importers, putting their food-insecure populations at particular risk of tighter or pricier global supplies (see SAHEL: COVID-19 will exacerbate food crisis - April 23, 2020).

G20 agriculture ministers have agreed that emergency food trade policies should be "targeted, proportionate, transparent and temporary". They have also agreed not to impose export restrictions or extra taxes on food purchased by international humanitarian agencies. However, these promises are vulnerable to subjective judgments.

Demand-side

Reduced demand from developed-country markets for food commodities such as coffee will also lead to income losses for cash crop exporters such as Sri Lanka, Ghana, Kenya and Argentina. Meanwhile, the oil slump will hit exporters such as Nigeria, where over 7 million people already face a food crisis risk.

The decline in trade revenues will trim the ability of such developing economies to provide food support to vulnerable households.

Weak safety nets

The countries where food assistance is currently being provided have limited scope and flexibility to scale-up social protection.

Notably, widespread school closures have reduced access to school meals, which fill nutrition gaps for some 370 million children worldwide. WFP has responded by using schools as distribution centres and converting school meal services into dry, take-home provisions to improve household food access. However, this has happened only in parts of 32 countries -- about half the countries WFP usually operates in.

Livelihood risks

Food insecurity will also be intensified by increasing employment vulnerability.

Work

The World Bank expects the crisis to push 40-60 million more people into extreme poverty this year, including 23 million in Sub-Saharan Africa and 16 million in South Asia, as livelihoods are lost.

Some countries with international travel closures, such as Australia, may open borders to migrant workers, especially in agriculture, to maintain their own food production. However, this will help only a small section of migrant labour. Moreover, complications in picking highly perishable fruit and vegetables will disrupt supply and raise prices later in the year.

Remittances

20%

Expected drop in remittances to developing countries in 2020

The World Bank estimates a 20% decline in remittances to low- and middle-income countries in 2020 to 445 billion dollars from 554 billion in 2019, due to the economic recession in upper-income countries. Remittances support basic household needs in populous, migrant-exporting countries such as the Philippines and Pakistan, as well as small islands such as Tonga and Vanuatu.

Worst hit will be those with both high remittance dependence and a pre-existing food crisis such as Haiti, Somalia, Yemen or Zimbabwe.

As incomes fall due to higher unemployment and lower remittances, food-insecure households will switch to less nutritious food, and reduce health and education spending, widening longer-term development gaps.

Remedial strategies are emerging, but slowly (see INTERNATIONAL: Food retailers will innovate to survive - February 24, 2020). Mobile phone-based payment services are being stepped up for cash transfers to vulnerable households, and other e-market services such as online food shopping, are also increasing. One such app has been rolled out by the Uttarakhand state government in India.

Locust infestation

In East Africa, some 20 million people are already food-insecure; this number is expected to reach 34-43 million in the next three months.

In addition to impacts from the COVID-19 crisis, a second wave of desert locust swarms in the region poses a further threat to agricultural production in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia, which were already hit hard by a first wave earlier this year (see EAST AFRICA: Locust control will require coordination - February 24, 2020).

- Unlike that first wave, the second wave will coincide with the planting season and damage seedlings. Eggs laid during this period will hatch in June, which could see a third wave arrive just as the harvest is underway, with the potential to cause even greater crop damage.

- A 1-square-kilometre swarm can eat enough food for 35,000 people, and damage can sometimes be total (100% crop loss). Some swarms are dozens of square kilometres in size, and their highly migratory nature impedes control efforts.

- The swarms can grow exponentially; in the worst-case scenario, without control measures and with perfect breeding conditions, swarms can grow by a factor of 20 per generation, meaning a third generation could be up to 400 times larger than the first.

Many of the affected countries lack significant control capacity, and pandemic-related restrictions on movement and trade are slowing the import of resources such as fumigators, insecticides and spraying equipment for aircraft.

Wider areas also face rising risks: Yemen, Iran and Pakistan are also expected to suffer renewed crop damage from new swarms, while other food-insecure countries such as Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda could face more swarms, which could even hit West Africa as the year progresses.

Outlook

Demand for food aid is rising just as donors' capacity is stretched:

- The WFP has called for 12 billion dollars in increased funding in 2020, including 1.9 billion for immediate crisis responses such as pre-positioning food and cash transfers. It has thus far received 1.1 billion.

- Food security is a major goal of the UN's revised 6.7-billion-dollar pandemic humanitarian appeal. It has received 13% of this, limiting the implementation of time-critical humanitarian support.

Significant new resources will be needed quickly as the pandemic pushes vulnerable sections into crisis situations. The most vulnerable are the 183 million people that last year faced Phase-2 food insecurity (characterised by borderline food access), who could fall into Phase 3 or worse, and the 821 million people who were undernourished before the pandemic began.