Prospects for global development goals to end-2020

Progress on UN Sustainable Development Goals faces serious new risks from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Updated: Nov 18, 2020

No country was on track to achieve all of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 as of last year. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic this year is threatening to halt, or even reverse, improvements in key areas.

What next

The pandemic will widen the gap between the rhetoric and reality on the SDGs in the second half of 2020 and in the next few years, endangering both recent progress and the prospects for future international development cooperation. Meanwhile, the status of the SDGs as a non-binding soft treaty will make it difficult to hold governments accountable for lack of progress.

Strategic summary

- Public and private funding shortfalls are a rising challenge to achieving the SDGs both globally and at the national level.

- National governments are likely to prioritise economic recovery from the pandemic even if that involves neglect of some SDGs.

- Progress on critical goals such as eradicating extreme poverty, malnutrition and social inequalities will be set back due to the pandemic.

Analysis

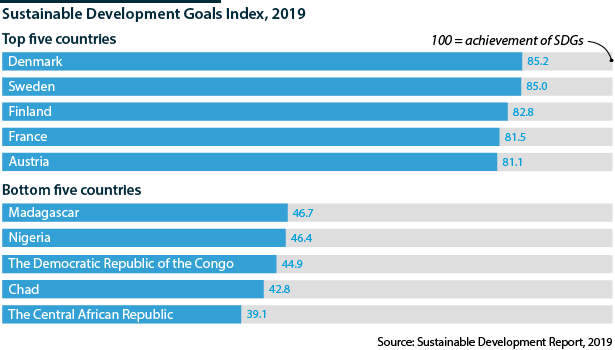

The Bertelsmann Stiftung Index report for 2019 scored Nordic countries -- Denmark, Sweden and Finland -- the highest for the third consecutive year for making progress towards most (but not all) of the SDGs, while the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Chad and the Central African Republic scored the lowest.

The rankings reflect a mismatch between the aspirations of the SDGs and the ambition in implementing targeted programmes by international donors and national governments. This gap is set to widen from this year onwards in key areas due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Poverty

Progress on poverty goals will likely reverse in 2020

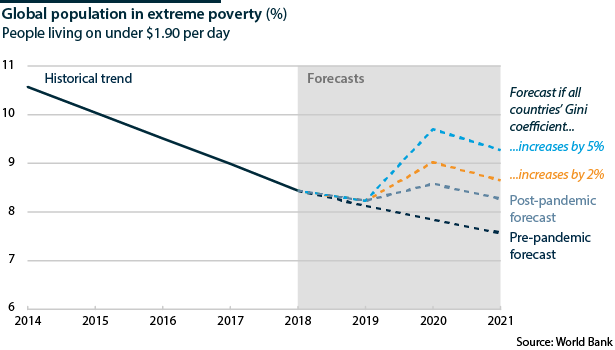

Half of the 193 countries that adopted the SDG agenda in 2015 are not on track to achieve the goal on eradicating poverty. At least 8.2% of the world's population was living in extreme poverty (ie, on less than 1.90 dollars per day) in 2019 and optimistic estimates projected this would decrease to 6.0% by 2030.

The pandemic has drastically revised projections: in April, the World Bank estimated that 49 million more people will suffer extreme poverty by end-2020. Of these, 23 million are projected to be in Sub-Saharan Africa and 16 million in South Asia. This will mark the first time when global poverty will increase in 30 years.

The impact is likely to be felt most strongly by those who live close to the poverty line as they face unemployment, loss of remittances and disruptions to basic services.

Most governments have responded to the pandemic with measures such as cash transfers and fiscal stimuli, but these measures are unlikely to be sufficient or to reach vulnerable sections such as refugees, migrant workers and the displaced.

Partly due to the pandemic's impact on poverty, the World Food Programme has warned that some 265 million people will suffer from acute hunger by end-2020 (see INT: Pandemic to deepen food insecurity beyond 2020 - May 13, 2020).

Climate and conservation

The long deprioritised goals on climate change, conservation of marine resources and sustainable management of resources on land are likely to see further neglect in the second half of 2020.

Before the pandemic, the trend on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions was travelling in the wrong direction even though climate change goals require emissions to fall 45% by 2030 from 2010 levels.

The percentage of forest area fell from 31.9% of total land area in 2000 to 31.2% in 2019, showing a net loss of almost 100 million hectares of the world's forests (see INTERNATIONAL: Land misuse poses long-term threats - November 26, 2019).

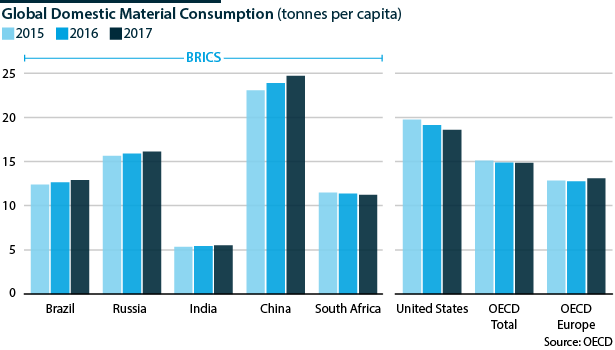

The rate of domestic material consumption per capita, which reflects progress in promoting growth while preventing environmental degradation, also remains disappointing. The figure rose across major economies in Europe and in BRICS countries except South Africa between 2015 and 2017, according to OECD data.

Despite the Paris Agreement, the Climate Action Tracker assessment shows that:

- only Bhutan, Ethiopia, India and the Philippines have made both commitments and efforts to help keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius; and

- only Morocco is on track to meet the target of keeping warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Policies and programmes in Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United States receive the lowest possible score.

The pandemic has delayed climate-related conferences such as the COP26 designed to reaffirm national commitments, report on progress and give visibility to climate advocates. Moreover, the economic shutdown precipitated by COVID-19 and the corresponding decrease in GHG emissions this year are also likely to be short-lived absent deeper policy changes such as increased regulation of airlines.

Financing challenges

The pandemic will undercut financing for SDGs (see INTERNATIONAL: COVID-19 will complicate global aid - April 16, 2020).

Aid

Net overseas development assistance (ODA) increased only slightly in 2019 to reach 152.8 billion dollars, while humanitarian aid from the 30 high-income countries in the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) fell 2.9% in real terms for the second consecutive year to 15.4 billion, according to OECD data.

At the national level, while countries have made commitments in their national plans to the SDGs, these commitments have not necessarily been reflected in budgetary allocations. Analysis of the submissions by 47 countries on SDG progress in 2019 showed that only 30% of the reports included specific details about the budget for SDG implementation.

As the pandemic triggers a global recession this year, ODA, humanitarian aid to DAC countries and budgetary allocations by developing countries for SDGs are likely to dip, with the scale of the decrease depending on the depth and length of the recession.

Private sector role

Private support for SDGs will likely decline due to the global recession

The private sector is playing a limited role in advancing the SDGs.

Notably, the UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, representing nearly 4 trillion dollars in assets, has committed to moving portfolios to net-zero GHG emissions but only by 2050. The UN has noted that transformation is neither happening fast enough nor at the required scale, both of which require refashioning corporate governance and raising the bar for the role played by the private sector.

A bright spot appears to be the World Bank's Sustainable Development Bonds (SDBs), first issued in 2018. In 2019 the Bank issued bonds worth 54 billion dollars in 440 transactions to support the financing of sustainable development projects and programmes.

Although the returns on a specific SDB are not linked to a particular project or programme, the first impact report shows that these bonds have supported projects linked to SDG 3 (health), 5 (gender equality), 6 (water), 11 (oceans), 12 (cities) and 14 (consumption and production).

Yet further private sector interest in 2020 and beyond will be shaped by the pandemic's economic impact on corporate donors and participants.

Outlook

While governments of countries such as Norway and Ghana are proposing that the response to COVID-19 be linked to progress on the SDGs, other countries will prioritise specific sectors. A central focus will be the health sector, which is likely to benefit from investment in both staff and infrastructure, and greater attention to vaccine programmes (see INTERNATIONAL: Early vaccine may keep some distancing - May 12, 2020).

Yet trade-offs between the SDGs will be ignored. For example, while governments are mitigating the economic impact of the pandemic through cash assistance to individuals and businesses, there are few measures to use the opportunity to push sectors with a high carbon footprint (such as airlines and automobiles) to overhaul practices.