Prospects for the global economy in 2021

The world economy is recovering unevenly from the deepest and broadest recession since the Second World War

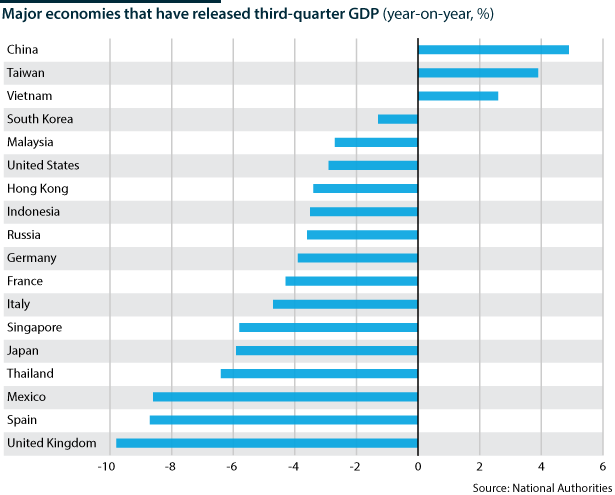

While every economy contracted in the first half of 2020, many rebounded from mid-2020 and some East and South-east Asian economies in particular are growing steadily. Europe and the United States may slip back into recession in the northern hemisphere winter. If vaccination succeeds, the advanced economies will recover robustly from mid-2021. Few emerging markets will be widely vaccinated by end-2021, restricting, if not negating, their recoveries.

What next

Retail, hospitality and domestic travel should recover robustly but vaccine inequality will prevent tourism recovering fully. Bankruptcies among previously productive firms, along with the subsidised survival of low-productivity firms, will reduce productivity. Rising debt costs will push fragile economies towards debt distress and curb developed states' ability to sustain fiscal stimulus; premature fiscal tightening is possible. Major central banks and the IMF can prevent contagion, but crisis-hit countries will face markedly weaker recoveries.

Strategic summary

- Inflation is unlikely to rise markedly as demand is very uneven, excess capacity is high and oil prices remain volatile, yet it remains on investors’ radars.

- The world economy could divide between nations vaccinated against COVID-19, and those not, with dramatic implications for trade and GDP.

- EU coordination is needed to avoid Southern European tourism losses creating a wider and deeper socio-economic depression across the continent.

- China is aiming for technological self-sufficiency and 'dual circulation', i.e. more domestic reliance; both imply less import demand for high-value products.

Analysis

Many sectors and developing economies have suffered far more disruption than in 2008-09, although the financial sector has continued to function. In 2008-09, G20 cooperation, the support given to the financial system, China's fiscal stimulus (around 13% of GDP) and a rapid commodity price rebound fuelled robust recovery. This time, high-income economies have announced broader economic stimuli and aid has increased, but actions have been uncoordinated. East Asia is recovering well, yet oil is unlikely to breach USD60 per barrel. Reflecting the depth and breadth of the crisis, the recovery will be highly uneven.

Pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical policies

Vaccine progress is promising, but even in high-income nations that have pre-purchased supplies, it will take until mid-2021 or beyond to distribute enough doses to lift non-pharmaceutical measures such as distancing (see PROSPECTS 2021: COVID-19 - November 19, 2020).

China and Russia have allowed vaccinations outside trials, but many low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) will rely on initiatives including COVAX, a WHO/GAVI-led arrangement that 80 self-financing countries have signed up to. A further 92 LMICs are eligible to benefit from the COVAX Advanced Market Commitment (funded by sovereign and private donors). Most LMICs are unlikely to achieve widespread vaccination by end-2021.

Logistical obstacles will impede speedy vaccination

Logistics planning is underway, but this alone will not ensure a speedy rollout.

Supply and demand

Lockdowns and travel restrictions imposed significant supply-side constraints on economies, disrupting supply chains and cutting output and jobs. However, supply has recovered faster than demand. Demand for travel, hospitality and entertainment remains disrupted and looks set for a patchy recovery.

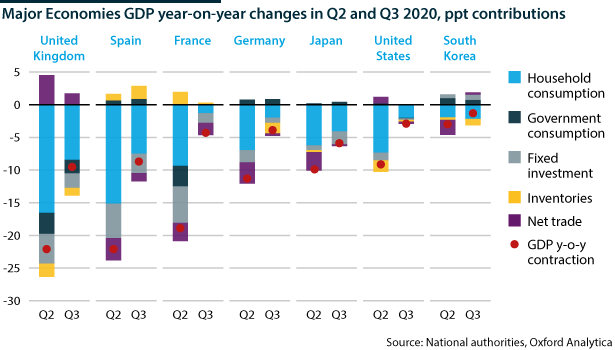

Country divergence will widen, partly due to COVID-19 spread, and partly due to different sectoral exposure. In East Asia, GDP will regain its pre-pandemic level by early 2021. The United States and Northern Europe may not recover this until 2022 or beyond. Southern Europe, South Asia and Latin America may take even longer.

Manufacturing, mining and construction have adopted policies including masks and distancing to continue operating. Distribution, and information and communications technology have surged. Housing and refurbishment demand has grown in high-income economies as people have taken advantage of remote working and low mortgage rates. However, the long-run consequences of changing work patterns have yet to be digested.

Several factors will influence the pace at which demand recovers.

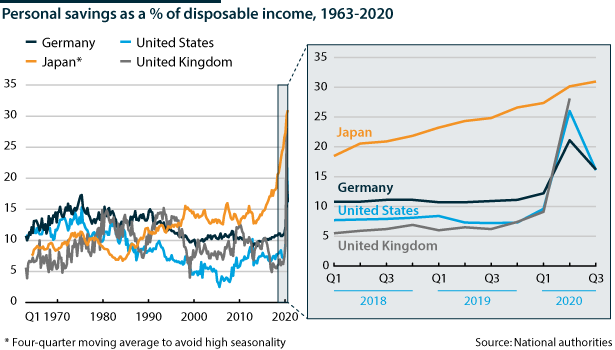

Pent-up demand

In countries able to enact such programmes, policies have supported incomes. Lockdowns reduced opportunities for spending but income support along with increased savings has enabled demand for consumer goods and services to rebound. Once a vaccine is distributed, travel, hospitality, arts, leisure and entertainment have the potential to recover rapidly provided that venues and companies survive. Domestic travel will recover quickest in Asia Pacific and North America as more than 80% of air travel occurs within the region. In Europe and the Middle East, the figure is just 25%.

Travel will recover faster in North America and Asia Pacific as domestic trips are dominant

Permanent scarring

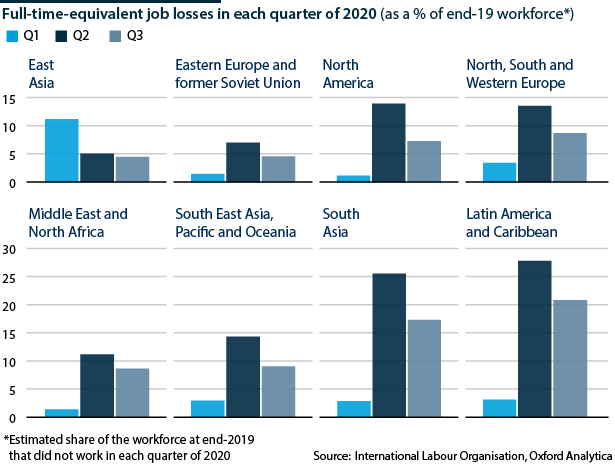

The more productive firms that disappear, the more sectors will be scarred. International Labour Organization data suggests that 16% of the global workforce stopped working in 2020, temporarily or permanently. After 2008-09, sectors including mining suffered project delays for years due to a shortage of skilled staff. Human capital and workforce participation, and consequently GDP growth, could suffer for years unless countries spend more on training, which may not appear an immediate priority (see INT: Joblessness will rise as job-save policies unwind - July 30, 2020).

Persistence of behavioural changes

Consumers will continue shopping online after the pandemic, and small and medium-sized shopkeepers will suffer unless they can successfully adopt multi-channel trading. This is increasing the number of individual consignments being shipped, straining long-distance transport forms and local delivery firms. Air travel prices could rise if bankruptcies reduce competition and climate action taxes the sector.

Consumer spending

Consumption, which accounts for 50-70% of national GDP, will drive the recovery, fuelled by unexpected household savings and post-vaccination demand for hospitality, non-essential retail, arts, leisure, recreation, entertainment and travel. However, even in high-income countries, vaccination will not be complete until at least mid-2021.

Real-time data from mobile phones and credit cards will signpost by-sector and by-country trends before the release of GDP and retail sales.

Investment

Private investment is likely to recover more slowly than consumption. The prospect of Europe and the United States lapsing into recession will make firms everywhere cautious of committing financial reserves and stoking excess capacity. Firms with less favourable financing opportunities might struggle to survive, with small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) a particular concern.

Productivity

The mix of how many unproductive firms survive, and how many productive firms fail, will be crucial. If only unproductive 'zombie' companies fail then national productivity will rise. However, crises can cause productive companies to fail while support schemes may keep zombies alive.

Studies suggest that in North America, Europe, Japan, China and other major emerging markets, as many as one-quarter to one-third of listed companies are unproductive. More zombie firms, higher unemployment, skill losses and SME closures threaten to shift productivity growth downwards.

Once the recovery builds momentum, firms with large reserves could unleash funds, boosting investment and innovation. Pandemic turbulence could spark higher productivity once new technologies overcome initial costs, but this is unlikely in 2021.

Trade

Overall, trade has fallen less relative to GDP than in 2008-09. Demand for non-traded services such as retail and local hospitality has been hugely disrupted, while demand for some highly traded sectors including electronics and medical supplies has surged. The relatively smooth functioning of global finance has also kept trade moving.

Nevertheless, renewed restrictions in Europe, the United States and various emerging markets will slow goods and services trade in the coming months. Tourism may be the slowest sector to recover, damaging countries heavily reliant on it (see EU: Travel coordination failure may spur depression - October 28, 2020).

US President-elect Joe Biden will adopt a softer approach towards multilateral institutions. However, protectionism is unlikely to reverse significantly even if rhetoric softens.

The US veto of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism may be resolved, allowing cases to progress and decisions to be legally binding. Further reform will be limited (see INTERNATIONAL: WTO marginalisation crimps world trade - August 4, 2020). Preferential trade agreements -- reciprocal deals between two or more partners - will progress, especially regional ones. Asia's Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership is in force and the African Continental Free Trade Area will take effect in January.

Policy support

The recovery will depend not only on vaccination, and the evolution of demand and supply, but also on fiscal and monetary policy. International relief will matter too.

Fiscal policies

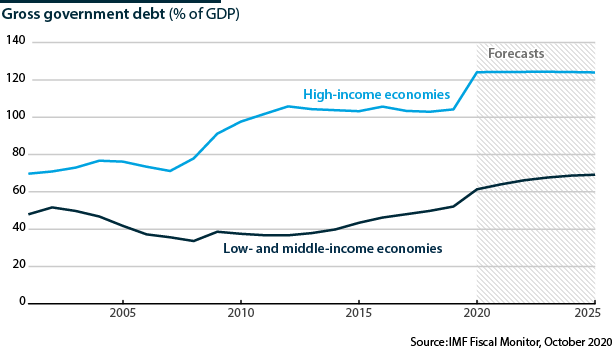

Limited financial or political space, or both, will curb many countries' scope for further stimulus. Debt as a share of GDP is starting to look alarming across many countries. Even with interest rates historically low in developed and developing countries, high debts risk provoking financial market repercussions and the share of debt service in government budgets will only rise. Interest payments alone risk crowding out spending on social services, education and infrastructure, threatening green energy projects and hopes of 'building back better'. Yet high-income countries still have leeway to expand debt.

Spending cuts could derail efforts to raise human capital and reduce carbon emissions

The UK economy is likely to suffer the largest recession among the G7 in 2020, having lost four times as much GDP as the United States in the third quarter, year-on-year, and around twice as much as the euro-area. As a result, while the government may come under pressure to expand policy, at the same time it is starting to consider spending cuts and tax increases. Other governments, whether high-, middle- or low-income, will also find themselves having to balance supporting economic recovery with ensuring budget sustainability.

Renewed COVID-19 disruption in Europe and the United States will increase calls for further stimulus. Biden is under pressure to agree a fiscal package and is likely to have to settle for less than the USD2.2tn in the latest iteration of the HEROES Act unless his party wins both Georgia run-off races for the US Senate (see PROSPECTS 2021: US economy - November 25, 2020).

Renewed European lockdowns increase the importance of speedy distribution of the EUR750bn (USD898bn) European recovery fund. However, some countries, especially in Southern Europe, have a poor record of deploying EU resources. Moreover, Poland and Hungary have delayed the recovery fund to stymie a rule-of-law scheme.

In emerging markets, India has restricted spending, fearful of a credit rating downgrade, but the combined deficit of the central and state governments could still rise to 13% of GDP by March 2022. A downgrade would reduce its capacity to borrow money and manage its debt (see PROSPECTS 2021: India - November 12, 2020).

Brazil distributed emergency payments to almost one-third of the population, mitigating pandemic-induced disruption but driving the budget deficit above 10% of GDP and raising fears about access to finance if the recovery falters.

Even China, and other East and South-east Asian economies, despite smaller GDP losses and faster recoveries, face pressure to cut spending as this would ease fears about rising debts damaging financial stability.

Monetary policies

Monetary policy is already loose worldwide, and this, together with international aid for LMICs, has lessened the financial market shock. Nevertheless, many countries face financial and political constraints to expanding fiscal policy, and for high-income economies, extra stimulus may well come from monetary policy.

Expectations are rising regarding an increase in the ECB's Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, under which it is buying EUR1.35tn of commercial banks assets. The ECB could also make more use of targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). Under TLTROs, banks lending a certain amount can then borrow at a rate as low as minus 1%; ie, the ECB effectively pays firms to borrow, then the firms can lend this out at a higher rate. The strategy review concludes in 2021 and is likely to follow the Federal Reserve (Fed) in recommending a symmetric inflation target around 2% to increase flexibility.

Further Fed stimulus is unlikely because the Fed looks to set policy several quarters ahead, and expectations are high that vaccination will get underway. Nevertheless, economic news will weigh on decisions.

The credibility of the major emerging market (EM) central banks has improved to such an extent that 13 have adopted forms of quantitative easing. However, EM central banks, including in Asia, might struggle to loosen policy further without stoking fears of inflation and outflows. Countries that see their recovery falter could be forced to tighten policy. More EMs are likely to have to seek international aid.

International aid

Recession and lower commodity prices, tourism, remittances and foreign investment threaten to push many LMICs into debt distress (see INT: Many middle-income states face a fragile recovery - November 24, 2020). At least 40 are in or near debt distress or default. In 2012, high-income countries and LMICs both spent about 5.5% of government revenue on debt servicing. This has fallen towards 4% in high-income economies but now exceeds 10% in LMICs.

>10%

Debt servicing as a share of government revenue in LMICs

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) runs to mid-2021 but is only available to the 76 lowest-income countries (LICs). Moreover, it just delays payments rather than restructuring them.

Lenders, including multilateral institutions, Paris Club and other bilateral creditors, most notably China, and private creditors including bondholders and trade creditors, are unlikely to agree a further extension. Without debt relief, disorderly debt defaults will occur, as with Zambia last month, potentially hiking the cost of borrowing for other LMICs on international markets (see PROSPECTS 2021: African economies - November 18, 2020).

Reducing the risk of contagion, the IMF has close to USD800bn to hand to meet the financing challenges. It is deploying USD250bn and 100 countries have required support. Hopes of an allocation of IMF special drawing rights have revived since the US election but similarly to the difficulty agreeing debt relief, gaining agreement will be tricky.

Outlook

The prospect of a vaccine dispels fears of a global depression, but decisions governments take in 2021 will be critical for a well-balanced recovery. Countries achieving vaccination sooner will find it easier to maintain political and social cohesion. The scale of workforce disruption will increase political pressure for remedies including social security, and reskilling workers to raise workforce participation, quality and productivity. However, many countries may have to cut spending or raise taxes to cover higher debt payments. Policy short-termism could impede efforts to tackle inequalities and address climate change, and raise the risk of social and political unrest.