Prospects for COVID-19 to end-2021

Return to 'normal' after COVID-19 will not be universal or simultaneous across the world

More than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries still face mass outbreaks, though a few are on the cusp of controlling their domestic epidemics. COVID-19 remains a complex disease due to lack of effective treatment, uncertainty around variants, marked differences by country and region on vaccination progress, and diplomatic bottlenecks.

What next

Countries will ease restrictions on mobility depending on their vaccine coverage, circulating cases and the impact of the disease on the mortality rate. This will result in a two-speed pandemic, with some, primarily high-income countries, racing ahead with vaccinations and reducing social-distancing measures, while lower- and middle-income nations fall behind. As vaccine supplies increase, the situation will stabilise, but full global recovery will be slow and staggered.

Strategic summary

- COVID-19 is likely to become endemic, with outbreaks more pronounced in regions with low vaccine coverage and many susceptible individuals.

- Travel is likely to remain complex in the medium term and could prove divisive if fast movers prescribe conditions that the rest of the world is not able to follow.

- Genomic surveillance in the long term may have to follow an enhanced influenza surveillance model to monitor the global emergence of new variants, especially if vaccines need to be routinely updated.

Analysis

Over a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, no part of the world is completely free from the disease. A few countries are controlling it through border controls and social distancing measures, such as New Zealand, China and South Korea. Others are controlling it -- or are close to it -- through vaccinations, such as Israel, the United States and the United Kingdom.

So far there is no evidence of natural herd immunity in any part of the world, even in areas that reported higher seroprevalence such as Brazil and India or in countries which did not lock down, such as Sweden. All three have experienced strong surges of the virus over the past year (see BRAZIL: Vaccine moves may not avert a third COVID wave - June 7, 2021).

Countries such as Singapore, Taiwan, China, New Zealand and South Korea were able to contain initial COVID-19 outbreaks better through early and strict lockdowns, effective contact tracing and extensive testing. However, most countries have not been successful at predicting surges or being fully prepared for one.

Most countries have not been prepared for COVID-19 surges

Extended social distancing measures are not sustainable. The only viable protection so far appears to be preventive vaccination.

Vaccine efficacy and coverage

Most vaccines that entered phase III trials have met and surpassed anticipated efficacy scores in protecting from severe disease.

Trial efficacy ranges from 60-95% protection from symptomatic COVID-19 and recent real-world data (for the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines) also support this. In addition, data from Israel and the United Kingdom also show 50-94% reduction in asymptomatic transmission, which is key to stopping the pandemic.

The levels of vaccines needed to control COVID-19 vary by country

With efficacy having been proved, the immediate concern is coverage: the point at which vaccinations will be sufficient to allow social distancing measures to be lifted.

Vaccine coverage

Two perspectives are important with regard to vaccine coverage. One is to protect the vulnerable and the other is to achieve herd immunity thresholds, whereupon even unvaccinated people are protected indirectly because it will be difficult for the disease to take hold amidst the many individuals who are immune. This is currently the case with mumps and polio.

Globally, herd immunity is unlikely to be achieved in the medium term, if ever, given the difficulties in procuring and delivering vaccines and the potential of variants (see INT: COVID vaccine roll-out will face multiple hurdles - October 14, 2020). Even if vaccines are widely available, they do not completely block transmission.

Endemicity of COVID-19 infection is therefore highly probable across the world as some transmission is likely to continue everywhere.

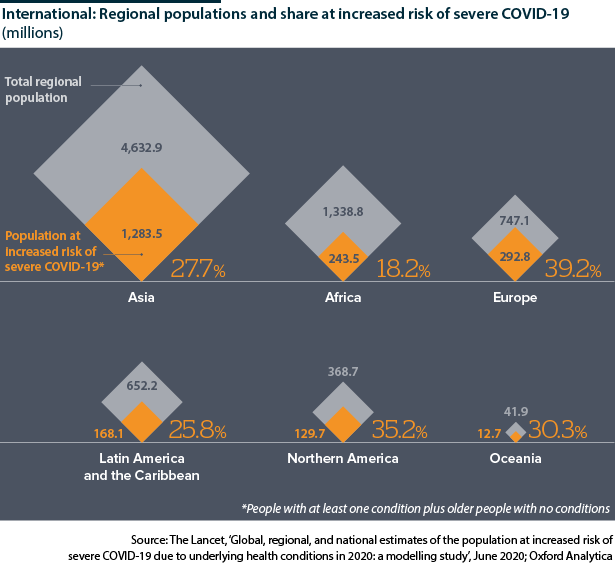

High-income countries have larger vulnerable populations than low-income ones

Protecting the vulnerable, however, is achievable in many countries. For example, countries that have young populations, such as Niger, where median age is 14.9 years and only 4% of its population is over 60, might be able to cope with a smaller supply of vaccines. By contrast, countries with older populations, such as Japan, where median age is 48.4 years and 34% of its population is over 60, will need more (see INT: ‘Finishing line’ of pandemic will vary - May 6, 2021).

Most low-income countries have younger populations, whereas high-income countries have high median ages.

Yet median age is not the only variable: confounding factors such as HIV prevalence, co-morbidities and health care provision can complicate matters for both.

Lack of healthcare provision in particular raises the risk of death significantly for older cohorts and vulnerable individuals, even if as a whole a country may record fewer deaths per capita. A Lancet study showed that Africa has the highest global mortality rate among the critically ill patients from COVID-19 (48.2% of critically ill patients died in Africa compared to a global average of 31.5%).

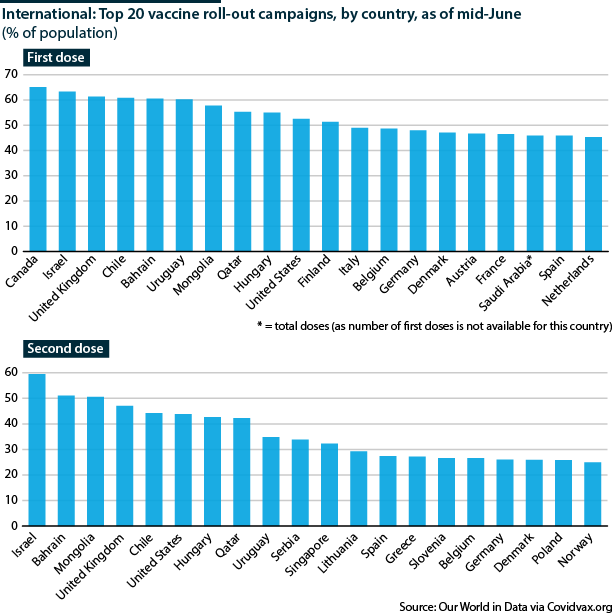

As of May, countries leading on vaccination with at least 50% of their population having had one dose include Israel, the United Kingdom, Mongolia, Bahrain, Canada, Chile, Hungary, United States and the United Arab Emirates. Of these, early vaccination appears to have avoided deaths in most except Mongolia, Bahrain, Chile and Canada. This discrepancy can be a factor of timing, circulating variants or varying social distancing measures.

The rest of the world lags further behind in immunisations. The majority of low-income and lower- and middle-income countries have administered doses to less than 10% of their population. The World Health Organization (WHO) Secretary General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in early June that high-income countries have administered almost 44% of the world's doses, and low-income countries just 0.4%.

Many of the low-income countries depend on a central pool of vaccines supplied through the COVAX scheme, the WHO's initiative to guarantee fair and equitable access to vaccines for all countries. The initiative aims to supply enough vaccines for 20% of the population of every participating country.

COVAX, however, is largely dependent on the AstraZeneca vaccine manufactured in India. India suspended exports in order to accelerate its own vaccination programme while it experienced a surge in COVID-19 during April and May, further constraining vaccine supplies available to other countries (see INDIA: Supply-chain blockage remains key jab problem - April 20, 2021 and see INDIA: Vaccine roll-out risks major coverage gaps - May 13, 2021).

Vaccine variety

WHO has approved vaccines from AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Moderna, Sinopharm and Sinovac. Other vaccines in use in some parts of the world include Bharat Biotech Covaxin, Gamaleya Sputnik V and those from Cansino, while Novavax is poised to file for approval soon.

Clinical trials with 'mix-and-match' doses have begun in Spain and the United Kingdom, and many European countries are recommending under 60s that received the AstraZeneca vaccine as a first dose can now opt for another vaccine as a booster to avoid thrombosis side-effects linked to the AstraZeneca.

Mixing-and-matching would allow more flexibility in vaccine roll-outs throughout the world. Preliminary results are promising and combining two different vaccines (one as the first dose and another as a booster) might even make some vaccines better than they are when used on their own.

The science behind combining doses is well known (and was previously trialled in the Ebola outbreak). However, an extensive variety of vaccines has never been available before for any disease, so practical efficacy and safety needs to be established for each combination, especially where different platforms are being combined (for example, the adenoviral vector-based AstraZeneca vaccine combined with the mRNA-based Pfizer vaccine).

Variants

The generally assumed herd immunity threshold is 70% of the population protected through vaccination. However, calculating this for every country is complex and can depend on transmission of the circulating virus, demographics of age and co-morbidities, vaccines' efficacy (against variants) and coverage.

The United Kingdom, which has one of the best surveillance systems in the world for infectious diseases, has reported 16 SARS-CoV-2 variants-of-interest. Several of them are thought to have increased transmissibility, especially the Alpha (B.1.1.7) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants (see INT/UK: Delta variant will fuel faster COVID waves - June 10, 2021). The Delta is also considered to double the risk of hospitalisation and evades vaccine immunity from one dose.

Other variants also reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, such as the Beta (B.1.351), but none completely abrogate it. Studies from the United Kingdom this week showed that both the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccine are over 90% effective after two doses against the Delta variant.

Variants could make protection for a country a moving target

Even if a variant reduces the efficacy of vaccines, vaccination will still be protective but for a smaller proportion of people than originally measured (see INT: Variants may delay, not derail COVID-19 control - February 15, 2021). This indicates that herd immunity can be a moving target and even in a fully vaccinated population, the proportion of people vulnerable to disease could vary.

Immunity from infection through vaccination is thought to last at least a year, and some early data predict it could be longer for people who were exposed to the virus naturally and subsequently vaccinated (see INTERNATIONAL: Immunity will shape pandemic's future - June 26, 2020). If it is found that the duration of protection varies by age or another demographic characteristic, certain groups of the population may need repeat vaccinations, while others may not.

So far, the effect of variants in the absence of vaccines has been devastating. Several countries saw surges fuelled by variants in the past year, including the United Kingdom with the Alpha variant, South Africa (Beta), Brazil (Gamma) and India (Delta) (see LATIN AMERICA: Region risks another lost decade - October 5, 2020).

However, the risk from variants in the presence of full vaccination appears to be low to moderate. In the United Kingdom, which is expecting COVID-19 infections to rise as social distancing measures are lifted, hospitalisations so far comprise more unvaccinated individuals than fully vaccinated. Data show 146 unvaccinated people hospitalised, compared to 20 fully vaccinated people hospitalised, between February 1 and June 7.

Travel outlook

As variants are better understood, and pharmaceutical interventions become more effective, the risk of severe disease is expected to become even lower.

The risk from severe disease will gradually reduce

In a few months, more countries will have vaccinated 70-80% of their population. As social distancing measures are lifted, it will become clearer how vaccines perform in the 'normal' world and if circulating disease is truly reduced. This may allow travel to resume slowly, starting with regional bubbles and 'safe' corridors (see INT: Vaccine passports will come before standards - April 16, 2021). If no further outbreaks occur, these safe corridors would likely be gradually expanded.

Both circulating virus and vaccine coverage will remain disparate across nations.

Regions of high vaccine coverage, such as Europe and North America, will probably not face a further high burden of disease and deaths, though pockets of low levels of vaccinations or unvaccinated communities could be highly affected.

Sparsely vaccinated countries or those with difficult to reach rural areas, including in Latin America, Africa and South Asia, will still see serious outbreaks that can particularly affect their vulnerable populations. These regions could become hotspots of infection and remain longer off the 'safe-to-travel' zone.

Reduction in severity is a major factor in how COVID-19 will be perceived in the future, and a substantial change in mortality will facilitate the easing of social distancing measures. Lockdowns may become more regional than national, but surveillance will remain important.

Vaccine travel requirements could be needed for years for certain countries

Long term, if countries eventually remain sparsely covered, a proportion of vaccines could be made available specifically for travel. Some specific vaccinations are currently required for travel to an endemic-affected area (eg, yellow fever), but COVID-19 carries bidirectional risk because of its person-to-person transmission. The situation could become more complex if destination countries recognise few but not all vaccines in use; although approvals are likely to be updated with time, as data emerge.

Yet variants have emerged that are capable of reducing the efficacy of current vaccines, albeit to different degrees. Often the impact of a mutant is only apparent after it has caused an outbreak, and has been reported in a country that is actively pursuing genomic sequencing. Therefore, a variant could emerge that can challenge preparedness measures or change disease manifestation.

Extensive genome sequencing in countries may eventually be replaced by a sentinel surveillance system, similar to influenza but will be required to be round-the-year and global.