Demographics will underpin global productivity trends

An ageing global population will constrain potential GDP growth due to lower labour supply

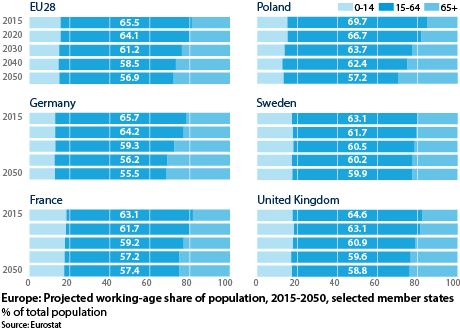

Unprecedented demographic change confronts the global economy. By 2050, populations will grow the fastest in Africa and India while Japan's will fall by 15%, Russia's by 14% and Germany's by 12%.

What next

By 2050, the global population will grow to 9.6 billion from 7.3 billion now. The number of over-65-year olds will triple while the numbers of working-age people and children will fall. Regional variations will be marked. In areas such as Africa and India, demographic change may support growth.

Subsidiary Impacts

- With no immigration, Germany's population will fall by 30 million by 2050 rather than the projected 10 million.

- High growth is probable in India and parts of Africa, where population growth is stronger.

- Governments facing demographic decline will need to reform their labour markets and health systems, while encouraging immigration.

Analysis

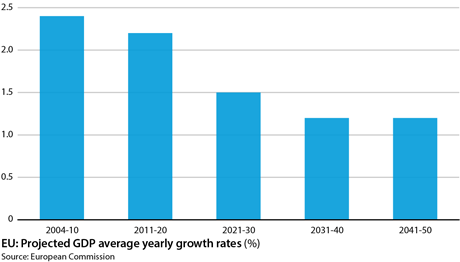

An older population is a less productive population. As the global population ages, potential GDP growth will be reduced by shrinking labour supply, higher wage costs, lower savings and lower capital through investment.

A Harvard study estimates that, had demographic decline begun in 1960, average yearly global growth from that year to 2005 would have been 2.1% rather than 2.8%, that is, 25% lower.

In the United States, average per-capita income would have risen to only 25,500 dollars in 2005 from 10,000 dollars in 1960, rather than to the 34,600-dollar income actually achieved. Additional projections can be produced applying this factor of demographic decline.

Average global GDP growth has been 2.5% since the 1973 OPEC oil embargo. If growth in 1975-2005 is reduced to 1.8% from 2.5% (as above, 25% lower), per-capita GDP will be 24,460 dollars in 2050 rather than 31,090 dollars under the 2.5%-growth scenario.

A wealthy OECD country with 45,000 dollars of per-capita GDP in 1975 will see this rise to 84,020 dollars in 2050, rather than 106,795 dollars.

Other threats to growth

These trends assume all other factors remaining unchanged, but they probably will not. Apart from demographics, growth depends on:

- the political environment;

- the level of corruption;

- the regulatory framework; and

- unexpected external shocks.

50%

Syria's GDP contraction in 2011-15War is bad for growth. Syria's real GDP contracted by 50% in 2011-15.

Corruption also affects growth (see INTERNATIONAL: NGOs will be slow to address corruption - May 5, 2016). The world's 15 least-corrupt countries are all, except for Barbados, wealthy OECD countries, while the world's 15 most-corrupt countries are all poor.

Legal and regulatory environments are also important. The OECD estimates that France could raise its GDP growth by 1.2% per year by increasing competition, liberalising its labour market, reforming governance and improving its tax system (see FRANCE: Reshuffle will not avert economic failures - February 17, 2016).

Regional variations

When making long-term investment, businesses consider the combined impact of demographic and political factors.

Africa

As demographic growth is the highest in Africa, the continent could experience strong growth. Even if per-capita GDP stays unchanged, population growth alone will lead to rising GDP, meaning more demand for products and services.

Ivory Coast, Senegal, Tanzania, Djibouti, Rwanda, Kenya and Mozambique enjoy annual GDP growth rates above 6%, though from a low base.

Among these countries, Senegal and Rwanda are ranked 44th and 54th respectively, out of 100 in terms of perceived corruption by Transparency International. The country ranked as 100th is seen as the least corrupt. For context, Germany is 81st and the United States 76th.

Though currently enjoying lower, or even negative growth, Zambia, Botswana, Ghana, Namibia and South Africa are also among the African states perceived as least corrupt, ranking 38th, 63rd, 47th, 53rd and 44th, respectively. They should be sources of growth.

India

India will be another important growth source, as a stable country with strong population growth and moderate perceptions of corruption. It is 38th in the corruption ranking, similar to Zambia.

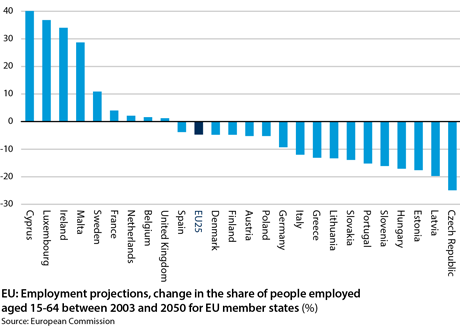

Europe

In Europe, the combination of relatively weak institutions and poor demographics will be worst in eastern and southern Europe. Political and demographic developments will be most favourable in France, the United Kingdom and Scandinavia.

Germany is an outlier. It lies at the heart of the European economy, has stable institutions and enjoys little corruption, but faces a rapidly ageing population.

Its skills-based, high-value-added economy and acceptance of migrants should deliver moderate economic growth and growing per-capita GDP. Germany's population declined in 2010, but large inwards migration has resulted in an overall population increase to 81.3 million from 80.2 million.

Germany's labour force expanded to 44.9 million people. Currently, there are 43 million people in work, the highest employment rate since reunification.

Even assuming 200,000-300,000 immigrants per year, Germany's population should still decline to 73.1 million by 2060, concentrated in eastern Germany, the Ruhr area and the countryside.

Major metropolitan areas will keep growing.

United States

The US senior population should more than double to 86 from 41 million people by 2060, but the overall population will grow by 89 million over the same period, underpinning growth.

The country has stable institutions and the largest share of global GDP.

Alternative scenario

The above analyses assume that current population predictions are accurate. Should Africa's population growth moderate on the back of rising GDP, as it did in Japan, North America and Europe, another scenario comes into play.

National Bureau of Economic Research data suggest that, as the birth rate declines, countries get a generational demographic dividend. Countries with a high share of children devote substantial resources to unproductive citizens.

However, as these children move into working life, both the labour force and productivity expand. As the population ages and this cohort retires, the country once again devotes substantial wealth to unproductive citizens.

Europe and North America enjoyed this dividend in the 1950s-60s, when growth was 6% per year. East Asia enjoyed it in the 1980s-2000s, when growth was also 6% per year on average and around 10% in China.

Political instability denied Latin America its demographic dividend. If population growth moderates, corruption is reduced and political stability achieved, this region could enjoy higher growth.

Fiscal effects

Countries with ageing population have fiscal effects more pronounced than growth effects

Countries with ageing populations see fiscal effects more pronounced than growth effects; health and social security costs rise as, with falling economic growth, tax revenue declines.

All countries in western Europe and in most of Asia will face such costs, but they will be most severe in countries with the most rapidly ageing populations, such as Japan and Germany. Due to a higher birth rate, the US population will age more slowly than the rest of the world's.

The global median age, which was eight years below that of the United States in 2010, is projected to be only five years below the US level by 2050. On the positive side, fiscal effects are easier to manage than growth effects.

These reforms would blunt the impact of ageing populations:

- increasing the female labour-force participation rate, raising tax revenues;

- raising the retirement age;

- moving from defined-benefit to defined-contribution pension schemes;

- favouring immigration, to slow labour force shrinkage; and

- linking healthcare costs to contributions; as the population ages, individual contributions or taxes will have to increase.

The combined effect of politics and demographics will affect the outcome of long-term investment decisions.

_350.jpg)