UK 'Brexit' vote will weaken EU

The complicated withdrawal process will shape UK and EU politics for years to come

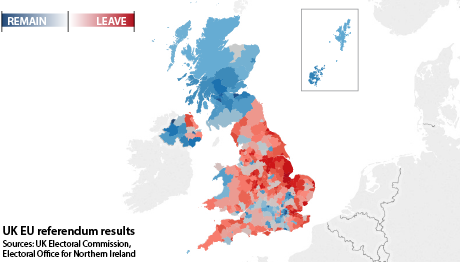

In a result that came as a surprise to markets, pollsters and commentators alike, the UK electorate yesterday voted to leave the EU by a 52-48% margin. This follows a campaign in which the 'Remain' side sought but ultimately failed to make the economy and, in particular, the economic risks associated with leaving the EU the main issue, while the 'Leave' lobby focused on immigration, the alleged cost of EU membership to the taxpayer and the advantages of enhanced sovereignty. This momentous vote means that the mechanism of withdrawal will dominate UK politics until 2020.

What next

The United Kingdom now faces the imminent prospect of a change in prime minister and a reshaped Conservative government, possibly under the leadership of Boris Johnson. It must then endure a three-to-four-year period of uncertainty as a Canada-style trade relationship with the EU emerges. The result is likely to boost Eurosceptic parties across the EU and trigger calls for referenda in other countries.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The United Kingdom's importance in Washington -- underpinned by diplomatic rather than military or economic clout -- is likely to decrease.

- Russia will seek to take advantage of a weaker and more divided EU.

- Relations with London will become a lower priority for Beijing, and some Chinese businesses will put investment plans on hold.

- Central European governments unhappy with EU pressure to admit migrants will call for a more diverse, less centralised model.

Analysis

The Leave victory came against the weight of expectations.

It appears to have been achieved by an alliance of the centre-right and much of the working class centre-left who found common cause in their opposition to EU membership and particularly the free movement of people, even if politically these two constituencies do not agree on much else.

There is also a generational and residential aspect to the result, with older voters much more motivated to vote and to leave the EU than was the case for younger electors, and rural England more disposed to quit than more urban areas.

Conservative negotiators

It has been assumed throughout that Prime Minister David Cameron could not and would not want to survive a Leave vote and oversee the negotiations necessary to implement that decision. He announced this morning that he would step down by the time of the Conservatives' annual conference in October.

His successor logically should be one of the leading advocates of the Leave campaign. That suggests two plausible individuals -- Johnson, the former mayor of London, and Michael Gove, the justice secretary -- who were the most prominent Conservative advocates of departing from the EU.

Although Gove might come under some pressure to stand, he has disavowed that ambition and in any regard would probably calculate that his chances of defeating Johnson in the ultimate ballot of Conservative Party members were modest.

Johnson is the early front runner to succeed Cameron

The contest is too early to call, but Johnson could become Conservative Party leader and prime minister with Gove overseeing the team conducting the negotiations on the United Kingdom's exit from the EU, either as deputy prime minister or foreign secretary, or in a bespoke position.

The unknown element is whether a senior figure -- notably Theresa May, the home secretary, who was a reluctant member of the Remain campaign -- challenges Johnson as a party-unifying compromise candidate, or cuts a deal with him.

Duration of negotiations

The mechanics of withdrawal are set out in Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. They involve a two-year process of dialogue before a departure becomes final, although this can be extended if there is unanimous consent to do so.

In practice, the government is likely to conclude that two years is too short a period and that it would be wise to agree some core principles for departure in a series of pre-negotiations before the article is officially triggered.

The United Kingdom's most likely exit point is 2019 or early 2020

Ministers would not, however, want an extended period of dialogue to undermine business and economic confidence in the United Kingdom. A target date in 2019 or early 2020 (certainly before the May 2020 election) is likely to be adopted.

The final agreement would have to be ratified by the European Parliament and, most probably, all remaining 27 member states, complicating the final timing.

UK-EU relationship

At the start of the referendum campaign there was an ambiguity in what the future model relationship would be.

Some Leave advocates, seemingly including Johnson, appeared to have sympathy with an 'EU-lite' relationship associated with Norway or Switzerland while others, including Gove, appeared to want a more detached outcome that would enable the United Kingdom to position itself as a more global actor.

The nature of the referendum contest appears to have moved this debate. The electorate is seen to have opted for withdrawal largely because of concerns over the free movement of people (with the disputed costs of EU membership to taxpayers a salient consideration as well).

A Norway- or Switzerland-style deal may be politically impossible

As any EU-lite deal akin to that of Norway or Switzerland would almost certainly have to involve the free movement of people and would probably include a UK contribution to the EU budget as well, such a bargain may now have to be considered politically impractical.

It seems more probable as a consequence that an arrangement more akin to the EU-Canada relationship would be more acceptable to both parties. That would imply a liberal EU-UK trade and investment regime, and an agreement to cooperate on strategic global issues.

Political consequences

There are several wider political consequences.

The first revolves around the response of pro-Remain figures within the Conservative Party and their willingness to serve in an administration that is pursuing a wholly new EU policy.

Second, there is likely to be exceptional acrimony within the Labour Party as well, with many Labour MPs blaming their leader, Jeremy Corbyn, for a half-hearted advocacy of the EU that failed to inspire Labour-inclined electors to back continued membership.

Third, the question of Scotland's continued participation in the United Kingdom has been reopened. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said this morning that a second independence referendum was now "highly likely", as Scotland (which voted 62% to 38% to remain) faced being taken out of the EU against its will (see UNITED KINGDOM: SNP to bide time on independence - October 30, 2015).

Finally, the status of the border between Northern Ireland and EU member Ireland will become salient again. The common travel area betwen the two provided under the Good Friday power-sharing agreement would come into question, with Irish politicians possibly arguing that closing it would be a breach of an international treaty.

Economic impact

The economic impact is the largest single unknown factor (see UNITED KINGDOM: 'Brexit' could hinder long-term growth - April 11, 2016).

In the short term, there may be a slowdown in economic growth with the risk of a technical recession. In the medium term, much depends on the arrangements that the United Kingdom concludes with its former partners.

The new Conservative leadership will be aware of these risks and is likely to adopt an economic agenda that promotes tax cuts over the original timetable for deficit reduction and outlines a sweeping deregulation initiative that would be implemented from the moment that UK membership of the EU ceased.

Shock in Europe

European Council President Donald Tusk has convened a meeting of the leaders of the 27 other member states on the sidelines of the June 28-29 Council to consider how to respond to the UK referendum result. Tusk said this morning they had hoped for a different outcome, but over the past two days he had spoken to EU leaders and they were determined to maintain their unity as the EU-27.

Managing the United Kingdom's departure will require major attention from EU institutions and member states and divert capacity from addressing other problems.

The EU will be diminished symbolically and practically, losing 65 million of its population (although probably Scotland and possibly Northern Ireland may eventually rejoin the EU) and one-sixth of its GDP.

It is a staggering blow to the 'European project', a move in a different direction to the non-EU European nations that still aspire to join that could lead some to reconsider.

The result will boost Eurosceptic parties

Eurosceptic parties across Europe will take heart, each pushing for a national referendum on recasting relations with the EU.

Party leaders that have already called for referenda on EU membership of their countries include Geert Wilders of the Dutch Freedom Party, Marine Le Pen of the French Front National and Mateo Salvini of the Italian Northern League.

Eurosceptic parties such as Spain's Podemos and Germany's Alternative fuer Deutschland are likely to benefit in upcoming elections. Established centrist parties may increasingly embrace Eurosceptic positions in an attempt to win back voters.

Those governments that want looser relations with the EU and a more free-market economic policy will miss an ally, while those on its eastern borders will be concerned at the signal sent to Russia that one of its two strongest military powers is disengaging from Europe.

The 27 will try to ponder the lessons for the EU from the UK referendum, but the variety of views on what those lessons are will blunt policy responses.

Some will conclude that UK departure is a shame but the EU must continue; others that a more 'social' EU is called for including greater integration and deeper economic and monetary union (with London seen as a major obstacle now removed); still others that 'Europe' has become too detached from its peoples and a major reappraisal is required; and others again that the possibility of a full political union is dead and buried.

_350.jpg)