Vaccine nationalism could prolong pandemic

High-income countries are already dominating pre-orders of COVID-19 vaccine candidates

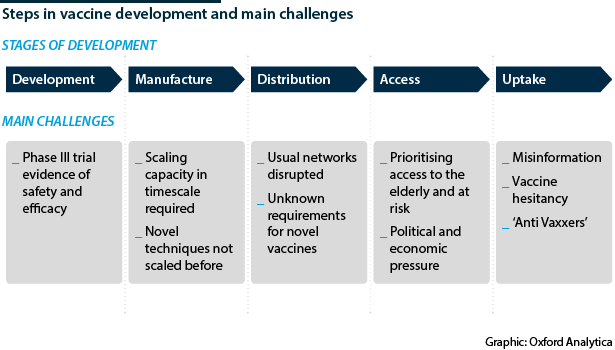

WHO Europe Director Hans Klugge yesterday said Europe can “learn to live” with the SARS-CoV-2 virus by adhering to measures including local lockdowns, without having a vaccine. Klugge is likely aiming to be optimistic. An effective COVID-19 vaccine is considered to be the only economically and humanely acceptable exit strategy for this pandemic. However, never before has a vaccine been developed, manufactured and distributed in the timescale now required.

What next

Optimistically, there may be an effective vaccine licensed and widely manufactured by end-2021. Even then, national competition will undermine efficient distribution and so lengthen the pandemic. High-income countries already have agreements with pharmaceutical companies for guaranteed access to vaccine candidates, pricing out lower-income countries. This will be marginally countered by global health institutions that will facilitate some access for low-income countries but will not cover the majority of the world’s population.

Subsidiary Impacts

- High-income countries will initially monopolise access to a vaccine.

- The country in which the vaccine is developed will be the very first to use it.

- Low- and middle-income countries covered by GAVI will gain some access to a vaccine, but it will not be comprehensive.

- Middle-income countries outside GAVI will likely be the last to get access.

Analysis

Global vaccine markets have a core ethical conflict: vaccine development is expensive and risky, but a cheap effective vaccine disproportionately benefits low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) because their healthcare systems have less capacity to deal with disease, making prevention more valuable.

Meanwhile, governments of high-income countries, which have an ethical obligation to protect their own citizens, will expect first access to vaccines they have funded and will have high bidding power for vaccines developed elsewhere. LMICs, on the other hand, are the least likely to be able to afford it.

In recognition of this inherent conflict, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI) and The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) have been created to improve access to vaccines for the world's poorest.

Securing vaccines

The procurement power of industrialised nations was seen during the swine flu outbreak in 2009 and is already becoming evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. The EU, United Kingdom, United States and Japan have already secured 1.3 billion doses of potential COVID-19 vaccines.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has the made the largest stockpile orders of COVID-19 vaccine candidates in the world

The United Kingdom has the largest potential stockpile per capita, having made orders of six vaccine candidates, totalling 340 million (mn) doses. The most pre-ordered vaccine so far globally, is the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca AZD1222, which has been proven to show the all-important dual antibody and T-cell immune response (see INTERNATIONAL: Immunity will shape pandemic's future - June 26, 2020).

Given that much of the funding came from the UK government at GBP65.5mn (USD87.5mn), it has first access and has secured 100mn doses. As an insurance policy, London has also placed advanced purchase orders of vaccine candidates using different approaches: 30mn doses from Pfizer-BioNtech SE, and a further 60mn each from Valneva and GSK/Sanofi.

United States

Similarly, the United States have an 'America First' policy in their USD10bn Operation Warp Speed. They have invested USD1.2bn in the AstraZeneca trial for 300mn doses, as well as candidate vaccines by Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, Glaxo and Sanofi. They are aggressively investing in manufacturing and distribution systems in anticipation of a vaccine candidate being licensed.

Elsewhere

The EU has also ordered 400mn doses from AstraZeneca as part of the Inclusive Vaccines Alliance set up by Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands. For China, AstraZeneca has partnered with BioKangtai to produce 200mn doses per year locally by end-2021 and has made similar deals with partners in Japan, Brazil, Russia and India. AstraZeneca has also reached agreements to produce a reported 150mn-200mn doses in Argentina and Mexico for Latin America. The order in which these countries gain access to the vaccine is not known. China and Russia also have their own vaccine candidates and Russia has begun a vaccination programme though a Phase III has not been published for that vaccine candidate.

Inequitable access

Inequitable access to a vaccine candidate is a future diplomatic powder keg, as it is likely a successful vaccine candidate will be announced at a time of asymmetrical international infection rates. For instance, there could be a scenario where Europe has access to 400mn doses at a time when the disease is largely under control, while it is running rampant in South Asia or Africa which have no vaccine access.

COVID-19 could become a travel-related disease, if it remains endemic in some areas and not others

This 'vaccine nationalism' of high-income states has already been criticised by LMICs and by Pope Francis, among others. Moreover, it is in the self-interest of high-income countries to support vaccinations in developing countries, to stop continued seeding of COVID-19 infections into their own territories.

WHO, GAVI and CEPI have formed COVAX, a means for LMICs to pool the risk of vaccine development by investing in a diverse portfolio of candidate vaccines and in return receive doses of an effective vaccine to cover 20% of their population by the end of 2021: an estimated 2bn vaccines.

Challenges ahead

However, vaccine manufacturing capacity is difficult to scale up quickly. One independent model by Airfinity, an analytics company, predicts the billionth dose will be made in the first quarter of 2022. The world's population is 7.8bn. To counter this, GAVI is using advanced market commitment mechanisms to incentivise companies to scale up manufacture capacity before their candidate has been licensed.

How quickly a vaccine is distributed will also depend on the type developed, for example if it requires refrigeration during transport, and if trade routes or borders remain closed due to COVID-19 control measures. Furthermore, many vaccine candidates are novel, and the techniques required for manufacturing and distribution differ significantly from those previously in place.

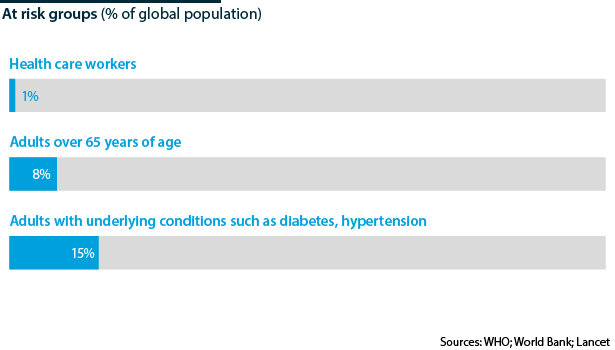

Ideally, access to the initial pool of vaccinations should be restricted to the 22% of the world population estimated to be most at risk due to underlying conditions and distributed globally on this basis. This would most efficiently reduce morbidity and mortality but not initially induce broad immunity within any country. However, in reality nations will maximise coverage of their own populations to expedite return to economic normality.

Finally, uptake of vaccine will require sufficient public trust, which will require prolonged public health messaging. With the rise of 'anti-vaxxers' and mistrust in science and governments fuelled by social media, this will be a final barrier to achieving broad immunity in some countries (see INTERNATIONAL: Falsehoods undercut COVID-19 responses - March 2, 2020).

Delivering a vaccine and ending the pandemic will require global collaboration. Historically, the United States took the global leadership role in combating public health threats and forming a large network of global health institutions. In 2003, President George W Bush's actions to counter the HIV/AIDS epidemic are thought to have saved 17 million lives worldwide. President Barack Obama led the successful suppression of Ebola in West Africa in 2014. However, COVID-19 has come at a time of waning US leadership, widespread nationalism and distrust in multilateral agencies. This will hamper international coordination but could improve under a different US administration.