Prospects for India to end-2021

The COVID-19 crisis is keeping the government under pressure

As India’s second wave of COVID-19 infections subsides, the government and businesses are looking with cautious optimism to the immediate future. However, only about 4% of the population has been fully vaccinated against the disease. While exports of domestically made jabs remain on hold, Delhi is attempting to strengthen trade relations with partners in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond.

What next

GDP growth will be subdued as the government struggles to raise consumer demand and curb inflation. India will try to accelerate its vaccine roll-out and may not resume its ‘vaccine diplomacy’ before the end of the year. This will create an opportunity for strategic rival China, already outperforming it in regional trade diplomacy, to undercut its neighbourhood influence further.

Strategic summary

- As household indebtedness holds back consumer spending, increased inflation will undermine policies designed to stimulate the economy.

- The inoculation programme will be the government’s main domestic challenge, although managing ongoing farmer protests will also be a test.

- Delhi will seek closer ties with ‘Quad’ partners Tokyo, Canberra and Washington as it tries to push back on Beijing’s regional influence.

Analysis

India's second coronavirus wave began in early March. On May 6, the country recorded more than 414,000 infections -- over four times the peak number of daily new cases registered during the first wave in 2020.

Several states have in the last three months imposed restrictions on movement and businesses, but unlike last year there been no nationwide lockdown.

Although daily new infections are back to the levels of mid-March, health professionals are warning of a third wave by October, if not sooner.

The authorities are attempting to speed up the vaccine roll-out. Fewer than 237 million out of India's 1.3 billion people have had a first dose and little over 52 million a second.

Economy

The pandemic's continued economic fallout will likely keep GDP growth low for the remainder of this year.

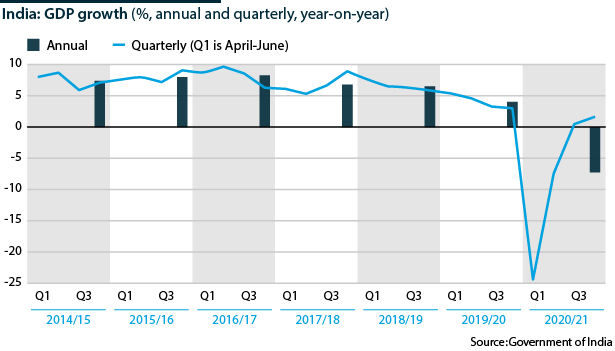

GDP shrank by 7.3% in the fiscal year ending March 2021. The fall was less than many agencies anticipated, mainly thanks to a return to year-on-year GDP growth in October-December 2020 and January-March 2021. The year-on-year GDP contractions registered in April-June 2020 and July-September 2020 were due largely to the countrywide lockdown.

The restrictions on economic activity recently imposed by many states are unlikely to push GDP growth back into negative territory, as there will be a favourable base effect.

However, constraints on production and consumption will endure.

Production bottlenecks will continue because of labour shortages in major towns and cities. Many migrant workers have been forced to return to their homes in rural areas for the second time in about a year.

The income benefits from good harvests may buoy rural consumption, but this is unlikely to compensate for overall demand compression. The household-debt-to-GDP ratio increased to 37.1% in the second quarter of 2020 from 35.4% in the first.

Boosting supply and demand in the economy may depend on raising public expenditure, but the government wants to narrow the fiscal deficit to 6.8% of GDP in 2021/22 from (a revised) 9.3% in 2020/21 (see INDIA: Reining in fiscal deficit will be a struggle - February 9, 2021). It is already likely to spend more than budgeted for the year because of its commitment to extending a free foodgrain scheme for vulnerable people until November and its promise of free COVID-19 vaccines for all adults.

Provision of free vaccines for all adults and foodgrain handouts will increase budgetary strain

Meanwhile, retail inflation is rising despite economic stagnation. The annual rate increased to 6.3% in May, due mainly to an uptick in food and fuel prices.

The Reserve Bank of India's target ceiling is 6.0%. Since its projections of 5.2% in April-June, 5.4% in July-September and 4.7% in October-December will probably be exceeded, it is more likely to raise than cut interest rates.

Politics

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is counting on a step-up in the COVID-19 vaccination programme to win over some of its critics and ease some of the pressure it currently faces.

The BJP had mixed fortunes in the legislative elections recently held in a handful of states. The defeat in West Bengal -- one of only three states where its alliance has never held power -- was especially disappointing for its leaders, as they had campaigned vigorously there (see INDIA: Election results give Modi’s rivals some hope - May 7, 2021).

Many farmers, especially in northern parts of the country, continue to oppose three agricultural laws passed in September 2020. They believe the liberalising reforms favour large corporations over cultivators.

Protests, which have lost momentum in recent months, could intensify. The government last week said it was ready to resume talks on the laws but ruled out a repeal.

Ongoing contestation could hurt the BJP in the lead-up to state elections due in early 2022. The reforms will likely be a key campaign issue in Uttar Pradesh, India's largest state.

The government could struggle to make progress in talks with protesting farmers

Manufacture of COVID-19 jabs will in the immediate term be focused on domestic needs rather than external demand.

By late March this year, India had shipped more than 60 million doses of locally made COVID-19 vaccines to dozens of countries in the form of commercial sales and grants. It hoped this would increase its soft power (see INDIA: Vaccine diplomacy brings money and influence - March 18, 2021).

It earned a measure of goodwill from the outreach, especially within the region, but the surge in its outbreak forced it to keep aside increasingly scarce shots for its own population. The last shipment of vaccines abroad was on April 22.

Domestic manufacturers have not managed to scale up vaccine production at the rate they envisaged.

International relations

Countries in the region that received COVID-19 jabs from India will rely more on shots from China. India recently suggested it could resume vaccine exports by October, but this will be difficult unless production picks up markedly (see SOUTH ASIA: China may trump India in vaccine diplomacy - June 8, 2021).

The pause in Delhi's vaccine diplomacy could disrupt plans for the 'Quad' -- the security grouping that involves Japan, Australia and the United States as well as India -- to distribute Indian-made vaccines across the Indo-Pacific. Each of the Quad countries wants to push back on China's growing power.

Delhi's trade policies could be a sticking point in its relations with Tokyo, Canberra and Washington, respectively.

Japan and Australia are part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) from which India withdrew before it was finalised last year. RCEP is a mega free trade agreement involving the ten ASEAN countries and five of its Asia-Pacific partners.

Delhi will resist calls for a U-turn on signing up and instead focus on developing its bilateral trading relationships with members. It believes RCEP's arrangement will lead to unfair competition from China, the pact's single-largest economy.

A complicating factor in India-US ties will be the digital services tax that Delhi introduced last year. The Office of the US Trade Representative says this discriminates against US firms and has threatened retaliatory tariffs on a range of imports from India.

India faces growing external pressure over its regulatory framework for online content

More broadly, India risks upsetting many of its partners with its new regulatory framework for online content that impinges on the functioning of platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter (see INDIA: New online rules risk state overreach and abuse - March 3, 2021).

Delhi will push back on accusations that it is stifling freedom of expression.