Prospects for the global economy to end-2021

Resurgent spending and loose policies are fuelling demand, but supply strains pose risks and many EMDCs are lagging

Strong economic activity in China and the United States is leading the rebound, with momentum also gathering pace in Europe and many developing countries. However, supply is struggling to keep pace with demand, and dislocation effects plus shortages of some critical goods and workers are raising prices. GDP growth forecasts for 2021 are skewed by the weak base for comparison; higher-frequency indicators will offer a better guide to new activity.

What next

Chinese and US activity should be resilient to near-term shocks and will power global trade. Europe faces more delays and risks but should rebound robustly. Signs of greater appetite for state intervention could help to correct inequalities. Emerging market and developing economies (EMDCs) that keep COVID-19 under control, are well diversified and have scope for policy adjustment will recover faster.

Strategic summary

- Global prospects are clouded by the risk of an emerging underclass of states that miss out on vaccinations and, later, on the green transition.

- FDI flows have fallen for a decade and a sharp uptick is unlikely; returns to FDI in EMDCs are falling and a sharp reversal is unlikely.

- Risks from high indebtedness may rise over the medium term, especially for any states that hike rates notably but see very modest growth.

- Signs of greater global cooperation are promising but far more is needed to meet EMDC infrastructure needs.

Analysis

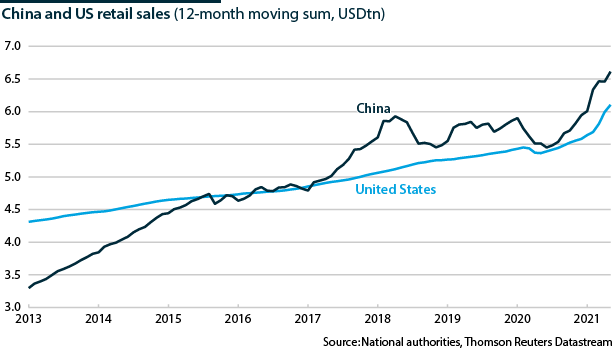

Demand is enjoying an even more V-shaped recovery than expected, fuelled by successful vaccination programmes and pent-up demand in North America, Europe and parts of Asia, as well as by China's supply surge. Savings built up during lockdowns are being spent in reopened sectors.

However, while the comparison with the slump in demand a year ago boosted the second-quarter annual growth figures, this will fade in the rest of 2021. Financial markets remain largely unruffled thanks to the ultra-loose monetary policies of the major central banks. Fiscal policy remains expansionary, with governments reluctant to withdraw pandemic support too soon and keen to progress with climate change mitigation programmes.

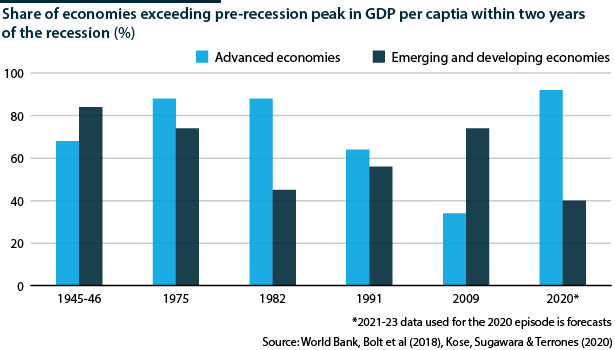

Yet demand is not recovering evenly. After the 2008-09 financial crisis, nearly 80% of EMDCs recovered their pre-recession peak GDP per capita within two years, while less than 40% of advanced economies did. This time, almost all advanced economies will recover within two years, but most EMDCs will not.

In recent decades, growth in EMDCs has sizably outpaced that of advanced economies but this EMDC 'premium' will be significantly smaller in 2021 and 2022 due to the fragility of the recovery in many EMDCs.

Demand/supply imbalances creating shortages

Supply proved more resilient to pandemic-related disruption than demand in 2020, with production and distribution challenges easing as many sectors adopted health and safety policies to continue operating.

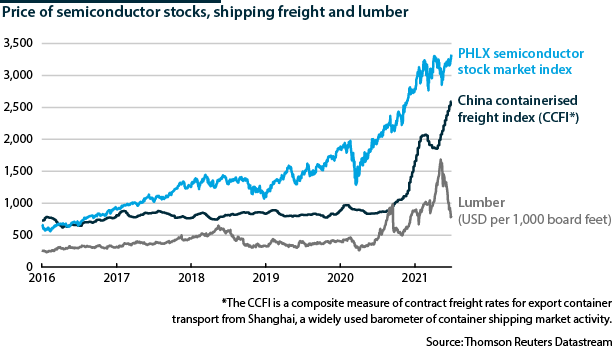

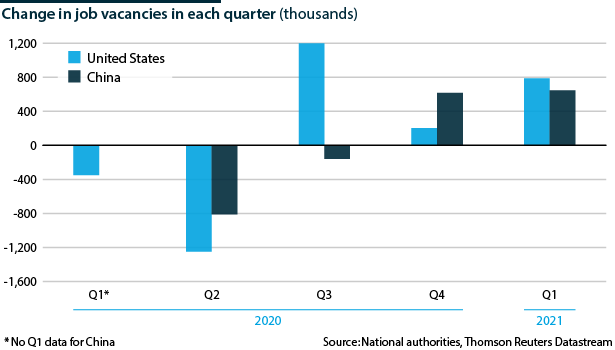

Imbalances have risen this year. Demand is outpacing supply for items including semiconductors, shipping freight capacity and raw materials, as well as for workers in sectors such as hospitality and construction. Shortages are raising concerns that recently high consumer and producer inflation figures (compared to a year ago) will persist.

Central banks in Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Hungary and Turkey have raised interest rates to try to curb inflation and exchange-rate weakness: more EMDCs are likely to follow suit. The major central banks will have to communicate their policy intentions clearly to anchor inflation expectations.

Trends including the persistence of behavioural changes, how private savings are spent and the pattern of the recovery of the labour market will determine:

- how long imbalances persist by sector;

- how much they disrupt the recovery; and

- how much they pressure policymakers.

Persistence of behavioural changes

Demand for workers in sectors that were severely disrupted but are now largely able to operate, such as restaurants and hairdressing, illustrates that spending on local services has rebounded in the developed world. These trends will accelerate as more countries enjoy progress on vaccinations. In some sectors and locations, staff have been hard to recruit, restricting the scale of the recovery. Adding to the labour-market changes, many former office workers will move to a hybrid working model: part-office, part-remote (see INTERNATIONAL: Part-remote-part-office work to evolve - April 22, 2021).

Although COVID-19 variants have emerged, the leading vaccines are still effective in sharply reducing hospital admissions and deaths. However, inequality of vaccine access will widen the gap between the relatively robust recoveries of the advanced economies and those of EMDCs.

During lockdowns consumers substituted spending on local services for spending on goods, especially online. This 'parcel trade' surge strained shipping freight capacity. Initially, the air traffic slump added to this but passenger airlines that have been able to adapt their business models have found cargo to be a profitable alternative to carrying passengers. Spending online will gradually fall as consumers reallocate spending towards services that reopen. Nonetheless, contract rates for shipping capacity will remain close to record highs for the rest of 2021 (see INTERNATIONAL: Container ship congestion to hit trade - March 9, 2021).

Commodities

The lumber price illustrates that once supply catches up and demand stabilises, many imbalances will ease and prices will fall. Lumber prices rose from USD374 per thousand board feet in January-June 2020 to above USD1,600 in May 2021 due to housing demand. They have since halved.

Other commodities have also seen this pattern.

The oil price recovered by around 40% from end-2020 to mid-March but has risen by less than 10% since. Further upside is likely to be limited as demand will stabilise and OPEC+ will adjust supply to match demand.

Food prices have risen by nearly 20% since the end of 2020 according to the IMF and will remain high, with weather-related losses likely in several crops. Further increases would hit countries reliant on imports, and especially EMDCs where food has a sizable weighting in the consumer price index.

The supply/demand rebalancing will vary by industry, and by how much pandemic-triggered behavioural changes persist. Entertainment is starting to recover within states but international travel will not recover until far more of the world is vaccinated.

Some supply/demand imbalances will not abate in the next year. The semiconductor market imbalance will persist, keeping prices of cars, computers and telecoms high (see INT: Semiconductor market imbalance will persist - April 6, 2021). The pandemic is increasing demand for these goods. Delivery times and prices for semiconductors have risen as production capacity is limited, design concentrated in the United States and manufacturing largely Asia-based. The United States, Europe and Asia plan to increase design and manufacturing capacity, but supply-chain changes will take years.

Remote working will keep demand for computers and telecoms high. The preference for transport that limits exposure to COVID-19 will keep automobile demand high. Prices for commodities such as copper that are crucial to clean energy infrastructure will also remain high (see INT: ‘Green’ tech to power industrial commodity prices - May 20, 2021).

The allocation of savings

Private savings surged as the large fiscal stimulus packages protected incomes while opportunities for spending on holidays and local services were limited.

Housing markets buoyant

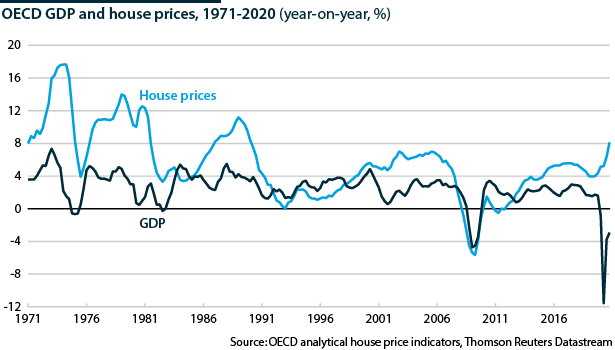

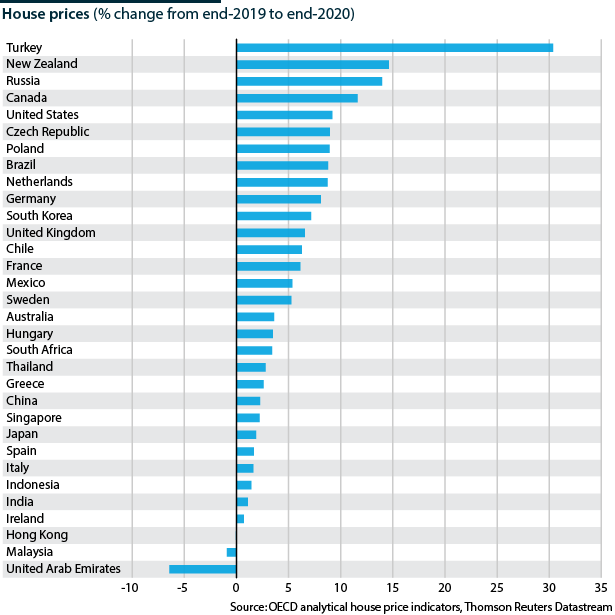

Lockdowns and remote working encouraged people to refurbish property or consider moving house, and to prioritise space and surroundings over the journey to work.

Temporary tax incentives in some advanced countries, and historically low interest rates in all countries, reduced house-purchase and mortgage costs. There are fears that the market could reverse as tax incentives are being withdrawn and interest rates are already rising in many EMDCs.

Many developed economies plus China, where the recovery has broad momentum, should be resilient to the removal of incentives and a gradual rise in mortgage costs. To reduce fear of asset-price bubbles building, the major central banks could increase restrictions on lending. Countries where the recovery is very fragile will be at risk of a broader correction.

Household consumption

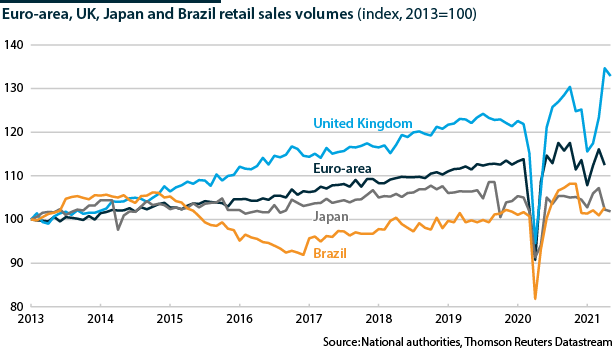

Some savings are being consumed as pent-up demand is released in reopened sectors. However, the trajectory of the retail recovery in the euro-area, Japan and especially Brazil illustrates that until populations are widely vaccinated, spending on retail, hospitality and entertainment will remain vulnerable to restrictions.

Stock market

The stock market has been another beneficiary of increased household savings and time spent online.

- The MSCI World equities index has risen by more than 12% this year after gaining 14% in 2020.

- US tech stocks led the 2020 rise, gaining 45%, although growth this year has moderated to 13%.

- The Chinese stock market has also stuttered, due partly to US-China trade tensions.

Tech stocks are vulnerable to declines if concerns about policy tightening or more regulation of tech intensify. However, the fundamentals of the sector are much stronger than before the dotcom bubble two decades ago. Furthermore, Bank of America's survey of fund managers this month showed that 72% agree with the Federal Reserve (Fed) that inflation is transitory. The risk of a sustained near-term sell off is fairly low.

Labour market recovery and restructuring

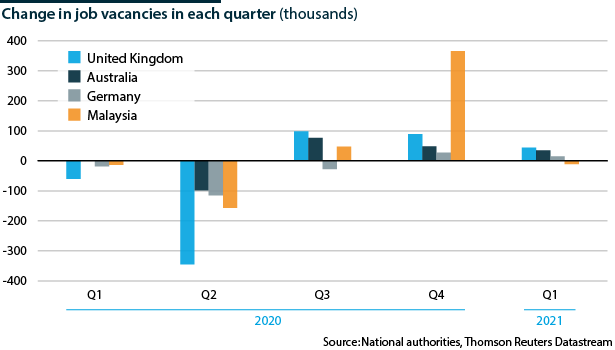

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated this month that 8.8% of working hours were lost worldwide last year, equivalent to the hours of 255 million full-time workers, or nearly 10% of the 2019 workforce. Half of this was due to people working fewer hours, half to job losses. In 2021, 3.5% fewer working hours are expected (equivalent to 100 million full-time jobs). In 2022, another small decline is expected.

Around 10% of the formal workforce has lost working hours or jobs

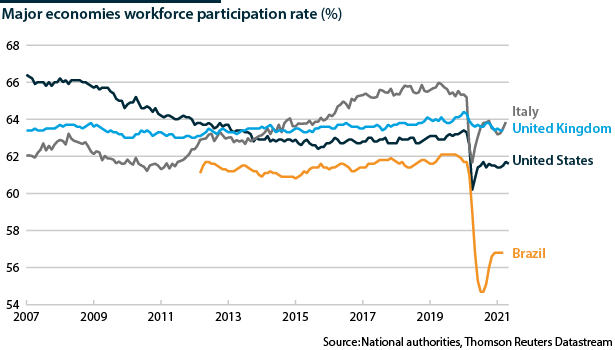

Shortages of workers in certain sectors reflect several factors. Workforce participation fell during the pandemic as some of the workers that left jobs chose to remain out of the workforce. While participation is recovering as people are attracted back by rising vacancies, it remains below pre-pandemic levels in countries for which there are high-frequency data.

The shortages also reflect skills mismatches and job churn, across as well as within sectors. Some workers employed in sectors hit by the pandemic have moved into sectors they see as more prosperous.

The ILO reports that the quality and security of jobs is declining overall (see INT: Joblessness will rise as job-save policies unwind - July 30, 2020). Self-employed workers, who often have fewer employment rights and access to social security, are rising as a share of the total. Demand for 'gig economy' workers is driving this. The shift towards part-office, part-remote working is also contributing. Highly qualified employees will have leverage over employers in determining their working arrangements. Mid-to-high skilled jobs will shift towards more self-employment and less full-time roles, and more tasks will be automated.

High job churn is likely to reduce productivity as too much churn too quickly leaves sectors short of experience and expertise. Over the medium term, however, the churn could spark innovation and raise productivity growth.

Policymaking

Worker shortages along with producer and consumer inflation have increased fears over whether the major central banks, and particularly the Fed, might tighten policy sooner than expected (see UNITED STATES: Inflation fears are exaggerated - March 24, 2021).

However, several factors will limit the persistence of inflation:

- the base effect of the comparison with the height of the pandemic will disappear;

- producer and commodity price gains are likely to level off; and

- supply-side strains will gradually ease.

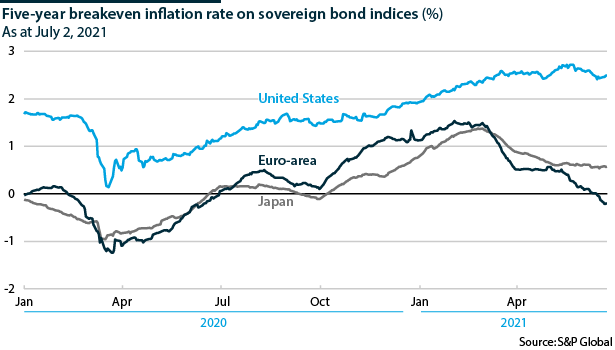

Moreover, there is still a lot of slack in the labour market in the United States, Japan and the euro-area. Wage bargaining mechanisms are also weak and there is little sign yet of an inflation-wage spiral building. Indeed, investor expectations of inflation five years out have fallen this month.

Economic and monetary fundamentals support the relaxed approach of major central banks to rising inflation

China will raise interest rates in an orderly fashion in coming months. This will reduce fears that the industrial sector is recovering faster than consumption, and that the rise in corporate debt has raised financial instability risks.

Several EMDC central banks have raised interest rates and more will follow. A fear for highly US dollar-indebted EMDCs is that global financial conditions could tighten when the Fed unwinds its quantitative easing programme or signals it will soon raise rates.

Tighter financial conditions would particularly trouble indebted corporations. Unlike government debt, almost all corporate debt tends to be owed on commercial rather than concessional terms. EMDC corporate debt rose to 119.4% of GDP by the end of 2020 from 101.9% at end-2019. Fed communication will be key to avoiding a 2013-style 'taper tantrum' which saw capital outflows from fragile EMDCs.

Fiscal policy

Both the United States and the euro-area are benefiting from fresh fiscal stimulus. US President Joe Biden passed the USD1.9tn COVID relief and stimulus bill in March, while disbursements from the EUR750bn Next Generation EU Recovery Fund agreed a year ago are underway. Policy will remain expansionary, even if political challenges hinder the rollout of the EU funds and make it difficult for Biden to pass further large increases in spending.

China, Japan and South Korea are also likely to keep fiscal policy expansionary into 2022. The pandemic has increased the appetite for, and acceptance of, state intervention. Several governments in developed countries, most notably the United States, are plotting a course towards a stronger, more redistributive state (see INTERNATIONAL: COVID may trigger an ideological shift - June 9, 2021).

However, in EMDCs, borrowing constraints and obstacles to taxing the wealthy will make redistribution harder. Many will come under pressure to reduce spending despite the fragility of the recovery and the risk of health crises.

Recovery unevenness

There are signs of more global cooperation. The IMF expects the USD650bn round of special drawing rights to be agreed by the end of August. Talks on the OECD proposals for global tax reform have made more progress this year than in the last eight years, though many obstacles remain (see INT: A fragile agreement on global tax reform is near - May 24, 2021).

The immediate impact of the SDR allocation will be limited. The debt relief measures are also inadequate because middle-income countries are excluded and the Western states that proposed them are no longer the main creditors to low-income countries (see INTERNATIONAL: Many developing states face weak growth - April 14, 2021).

Vaccine inequality will hold back the recovery because international travel will not recover until more countries are widely vaccinated. COVAX, the WHO/GAVI-led arrangement to provide vaccines to EMDCs in need, is behind its targets. Advanced economies have recently pledged to donate vaccines but not in numbers that raise the prospect of the world having a firm grip on COVID-19 by end-2022.

Similarly, global commitments fill little of EMDC infrastructure needs. The International Energy Agency estimates that in EMDCs excluding China, annual clean energy spending must rise sevenfold by 2030 for the world to meet the Paris agreement target of reducing net emissions to net zero by 2050 (see INT: Developing nations risk missing climate targets - June 17, 2021). A transformation of global cooperation will be needed to divert some of the developed world savings from stock markets and housing to EMDC infrastructure needs.

Outlook

The V-shaped recovery of global GDP growth and trade will continue, with the advanced economies and China likely to be strong enough to shake off near-term shocks. However, distributional conflicts will rise as economic and social inequalities test policymakers. Unevenness between countries will pose questions about global cooperation and aid for EMDCs struggling with the effects of the pandemic and climate change.